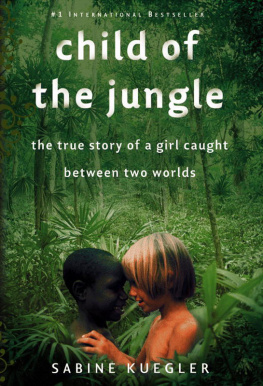

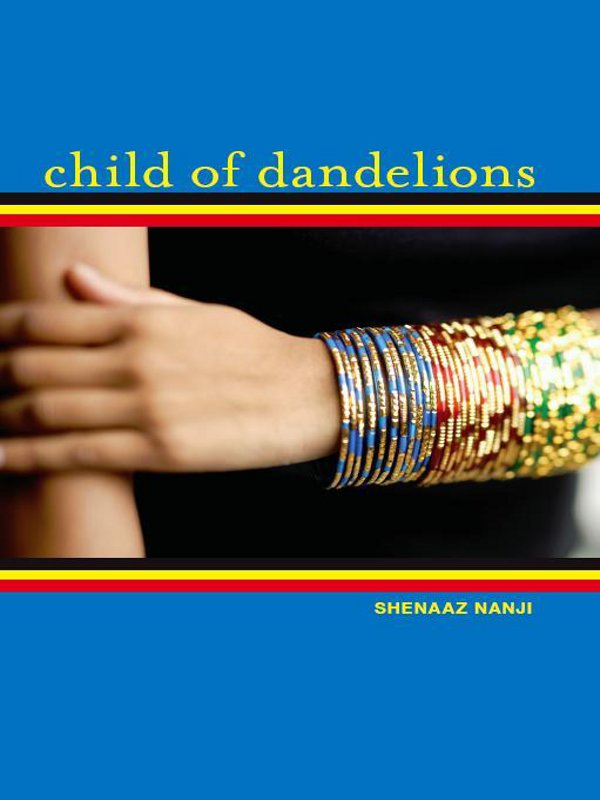

child of dandelions

A beautiful, touching story of a child caught between two worlds, in a country caught in the grip of a brutal army dictator. Shenaaz Nanji evokes wonderfully the purity and bewilderment of a child awakening to terror and discovering a wretched reality.

M. G. Vassanji, two-time Giller Prize winner

This is a gripping tale full of beauty and horror, friendship and betrayal, family and country, love and fear. It opened up a whole new world to me, peopled with rich, believable characters. Nanji never lets up on the tension inherent in the story. Historical writing at its best.

Carol Matas, award-winning childrens author

Drawn in part from the veteran authors own experiences, this deeply felt tale takes readers to 1972 Uganda... Readers will feel her inner conflict sharply, admire her resilience and quick thinkingand come away shocked themselves by the brutality she encounters during this little-known historical episode.

Kirkus Reviews

child of dandelions

Shenaaz Nanji

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Nanji, Shenaaz

Child of dandelions / by Shenaaz G. Nanji.

ISBN 978-1-897187-50-0

1. Amin, Idi, 1925-2003Juvenile fiction. 2. East IndiansUgandaJuvenile fiction. 3. Ethnic relationsJuvenile fiction. 4. FamilyUgandaJuvenile fiction. 5. Forced migrationUgandaJuvenile fiction. I. Title.

PS8577.A573.C44 2008 jC813.54 C2008-903918-1

Copyright 2008 by Shenaaz Nanji and

Front Street, An Imprint of Boyds Mills Press, Inc.

Design by Helend Robinson & Melissa Kaita

Front cover photo Asia Images Group

Dandelion illustration iStockphoto

Printed and bound in Canada

Printed on recycled paper

Second Story Press gratefully acknowledges the support of the

Ontario Arts Council and the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the

Book Publishing Industry Development Program.

Published by

SECOND STORY PRESS

20 Maud Street, Suite 401

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5V

2M5

www.secondstorypress.ca

With love to my family

and to the children of refugee families

Contents

Throughout history, cultures have suffered when poverty, prejudice, and intolerance have created breeding grounds for hatred and violence. This novel explores the consequences of such injustice and inequality on two friends and their communities.

Shenaaz Nanji

August 6, 1972

DAY 1

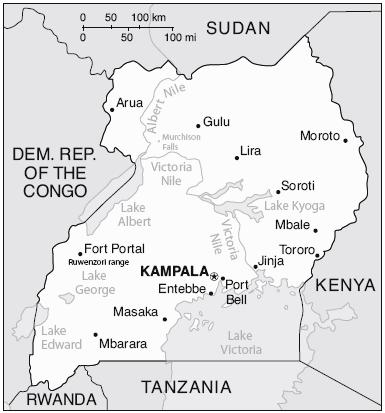

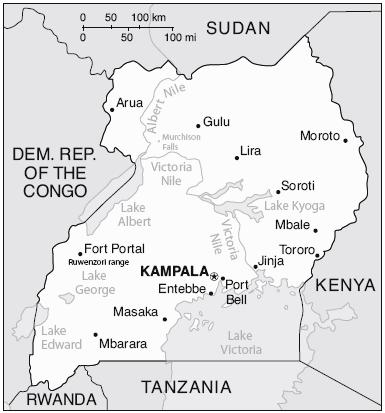

The river of jubilant people alarmed Sabine as they bobbed along Allidina Visram Street in Kampala. What was the event? she wondered. Not Independence Day. Anniversary of the military coup? No. Then what?

The August sun forced sweat down her forehead and along her neck. The road sweated, too; the melting tarmac oozed sticky black streaks. Sabine and her best friend were winding in and out of the spice-scented alleys of Little India when they ran into the parade.

The dark faces drew closer. Women in bright gomesi and headscarves danced, and bare-chested men punched their fists into the air, chanting, Muhindi, nenda nyumbani! Indian, go home.

Sabine felt she was drowning in their cries.

Her friend Zenabu pressed her arm. They mean British Indians, not you.

Sabine nodded, ignoring the burn inside her. She was born here. Her father was born here. They were Ugandans. Other Indians, like their neighbor Lalita, were British.

Scores of people thronged to cheer the demonstrators. They stood atop boxes, on cars, and on rooftops, waving fronds of the matoke, plantain, trees. The girls found themselves engulfed in the crowd jostling elbow to elbow in the heat. A bystander jabbed a finger into Sabines back. Eti, muhindi, go back to India!

Sabine turned around to see who had spoken, and spit grazed her chin.

She wiped off the insult, biting the inside of her cheek and restraining her tears. The man could not tell that she was Ugandan. I wish I were dark like Zena.

Zena glared at the man. Shes my best friend.

The man laughed. One day youll see with new eyes. He picked up a rock by the footpath and flung it across the street. Crash! The display window of Sari Fashion shattered, and shards of glass scattered on the road like a broken diamond necklace.

Sabine spotted an army truck in the corner of the alley standing idly by as the crowd cheered and chanted, Down with muhindi dukawallas! Down with the shopkeepers!

Flying stones, crates, cans, and street debris hit the windows of other Indian stores. People ran carrying radios, cash registers, and even sewing machines. Sabine and Zena rushed past the torrent of bodies, colliding with hands and legs, tripping over a headless mannequin wrapped in a sari, scrambling again, running, running, running.

Safely home in the comfort of the sitting room, Sabine heard on the radio that President Idi Amin had had a dream. In the dream God told him to expel all foreign Indians from Uganda. The newsman said, Hundreds danced on the streets to celebrate the Presidents dream.

Celebrate? How silly thought Sabine. Clearly, it was a riot.

Nonsense! Papa laughed his conch-shell laugh, and her little brother echoed it.

Mamas betel-brown eyes grew bigger. Sadru, we are Indians.

Ugandans, Sabine corrected, looking at Papa, who nodded.

In fact, we are even more Ugandan than the ethnic Africans. Not only were we born here, but we chose to be Ugandan citizens when other Indians remained British. Papa turned to Mama. He put his hand on her lap. Dont worry, Guli. We may be a handful of golden raisins among eleven million, but we control Ugandas economy. You cant bite the hand that feeds you.

Before Mama could respond, the newsman on the radio said, All foreign Indians will be weeded out of Uganda in ninety days. Today is day one of the countdown.

Sabine looked at Papa in confusion. Had the Presidents dream become law?

August 13, 1972

DAY 8

Sabine swung her satchel over her shoulder and climbed into the front seat of Uncles red Alfa Romeo. She could hardly wait to see Zena. Today they would trade costumes and practise a dance they were going to perform at the Presidents banquet on Independence Day, October 9. But first she freed herself from her tight black shoes. Then she peeled off the milky white socks that her mother insisted she wear. She stuffed the hated shoes and socks into her satchel and found her sandals, the ones like Zenas.

Sabine bent down to strap them on. She wished Papa were home. He had left on a business trip. The hourly countdown on the radio about the expulsion of foreign Indians had turned her mother into a bundle of raw nerves. Mama wasnt going to let her go to Zenas today because Mamas left eye was twitching, a bad-luck sign.

Thats an old wives tale, Sabine had said. Wake up, Mama. This is 1972!

Sundays belonged to Sabine. On Sundays she flew wild and free with Zena. And during school holidays the girls met at her grandfathers Kasenda farm, at the foot of the mist-laden Ruwenzori Mountains in Fort Portal. Bapa called the girls twin beans of one coffee flower.

Next page