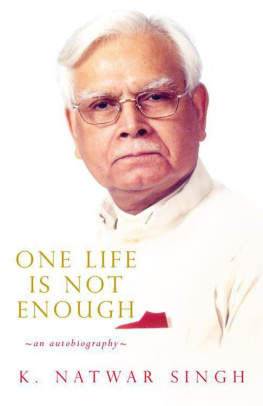

K. Natwar Singh is a well-known author, diplomat and politician. He has been ambassador to Pakistan, and was attached to the office of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi from 1966 to 1971. He was secretary general of the NAM summit held in Delhi in March 1983. He has been a member of the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha, and served as Minister of State and Minister for External Affairs.

He was awarded the Padma Bhushan in 1984. Since 2005 he has been Honorary Fellow of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. His books include E.M. Forster: A Tribute, Profiles and Letters, Heart to Heart, My China Diary and The Magnificent Maharaja. He lives in New Delhi.

1

An Ill-tempered PM

O n 23 March 1977, Morarji bhai Desai was sworn in as prime minister. The next day a top-secret telegram from the Ministry of External Affairs was placed on my office table. It said that I should immediately take leave. No explanation was given. I was flabbergasted. Later I discovered that my being Indira Gandhis man in London had done me in.

Morarji Desai arrived in London in early June to attend the Commonwealth Prime Ministers Conference. To my great surprise his host was High Commissioner B.K. Nehru. After all, he had, like me, defended the Emergency. Later I learnt that the good Nehru had got in touch with the new PM, whom he knew well, and had invited him to stay with him at 9, Kensington Palace Gardens, the ducal residence of the high commissioner. (Mrs Gandhi was livid when she heard that her second cousin was playing host to her principal political opponent.)

I became a non-person overnight as far as the high commissioner was concerned. My wife was recovering from a gall bladder operation. Our two children aged seven and six had not fully recovered from their tonsil operations. My mother-in-law kept in touch with us. She had been fed on horror tales about her son-in-laws crimes during the Emergency. After differences with Indira Gandhi, she had gone over to Morarji Desais faction a couple of years back. She was now one of the general secretaries of the Janata Party, and was in an unenviable predicament. Personal and political loyalties collided. My paramount worry was regarding my next posting. How long was I to keep cooling my heels? No one in the Ministry of External Affairs and hardly anyone in the high commission was in the least interested. Only two IFS officers did not desert me. One of them retired a few years ago. He too suffered on my account. When I became foreign minister, I made sure he got his due.

I have strong nerves. Defiance comes to me with ease. I did not and do not suffer fools. I also knew my worth. My five years with Indira Gandhi had bestowed on me a distinction few bureaucrats attain. My service record was the envy of many.

On the third day after Morarji Desais arrival, B.K. Nehru rang me up. What he said appalled me. Natwar, the PM tells me that you held a champagne party on 26 June 1975 [the day the Emergency was declared] at India House. Did you? I replied, Bijju bhai, on that unforgettable day you and I were at India House the whole time answering questions from the media. Besides, the news of the never-held party could not have remained a secret from the media, British and Indian, because the phantom guests would have certainly spread the news. To pull his leg I added, Are you sure you did not give a champagne party at your residence? He had a sense of humour. Laughing, he put the phone down.

Two days later the HC said the PM wished to see the discretionary grant register. How much did you spend out of it? Again I was outraged. I informed the HC that we had asked for a grant of 5,000, out of which we had spent only 450. I immediately had the grant register sent to him as the PM wished to see it. He obviously had nothing better to do. He did not believe what he saw. This is a false record. I know Indira used to send cash to Natwar Singh by diplomatic bags!

We all knew Desai had not the foggiest idea how diplomatic bags are handled. On arrival the officer, a first secretary, has the bag opened in the presence of several assistants, and the contents are distributed to the concerned personsletters, files, Indian newspapers. Then a list is drawn up. All these facts were placed before the prime minister, who dismissed them immediately. He apparently even commented to the HC that Indira must have sent the cash by some other means.

I was naturally anxious to know of my next posting. I was relieved to be informed that I had been appointed high commissioner to Zambia. I had been twice to the country with the decolonization committee. More importantly, I knew President Kenneth Kaunda well. He had come to New York in 1962 to appear before the committee as a petitioner, to expose the inequities of British rule in Northern Rhodesia, as it then was. Our instructions were to support him. I invited him for lunch and gave him a lift in my car. The permanent representative, C.S. Jha, an able diplomat, did not have any time to spare for Kaunda.

Two years later he came to the US as the prime minister of Zambia. From Washington he travelled to New York by train. The permanent representatives of the African and Commonwealth countries were at the station to receive him. When he spotted Jha he asked, Where is Mr Natwar Singh?

Had Desai and the MEA known this I would never have been sent to Zambia. Lusaka is 4,000 feet above sea level. The climate could not be better and there were no stacks of files to deal with. I spent two-and-a-half pleasant and rewarding years in Zambia.

I had easy access to the president. I played a lot of tennis, wrote a book on Suraj Mal, the real founder of Bharatpur, my home state. It was published in London. Lusaka was not London. But it had many things to its favour.

A few days before leaving London, a colleague of mine handed me an invaluable document, Dietary Preferences of the Prime Minister. Here it goes:

Carrot juice: only from the deep pink carrot grown in northern India.

Lunch: 5 pieces of garlic, must be freshly peeled before serving. Cows milk (lukewarm). Honey. Fresh paneer slices.

Fruit: banana, papaya, apple, pear, leechi, cherries, apricots and alphonso mangoes.

Dry fruit: cashew nuts, badaam, pista, moongphali dana (roasted).

Indian sweets: sandesh, pera, humchum, rasmalai, rasgoolla, gajar ka halwa.

The dinner menu was even more appetizing. His favourite drink was not mentioned. Everyone knew what it was.

Some Gandhian diet for a pseudo-Gandhian.

2

A Spat with Morarji Desai

F or all writers of history Morarji bhai Desai is a huge disappointment. When he died in 1995, at the age of ninety-nine, no comets were seen. The heavens did not blaze forth his death. His personality was that of a one- dimensional man. He was a competent servant of state but not a tribune of the people.

I was not an admirer. I actually had the chutzpah to take him on, thus earning his wrath when he was prime minister. I was cussedly defiant. In retrospect, I do concede that I should have been more circumspect. Here is the story. In August 1977 I arrived in Lusaka, capital of Zambia, to take up my post as high commissioner. The politics of southern Africa were in turmoil, and Zambia was a frontline state. Several important leaders of the freedom movements in South Africa, South-West Africa (now Namibia) and Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) found refuge in Zambia. These included Oliver Tambo of the African National Congress; Nelson Mandela was in prison and Tambo had been carrying the torch of the South African freedom movement. From Southern Rhodesia there was the well-known Joshua Nkomo, who had spent many years in prison (Robert Mugabe was in exile in Mozambique). From South-West Africa there was Sam Nujoma, who would later become the founding president of Namibia. India was helping each of them in every way except supplying arms. I was personally in touch with these leaders.