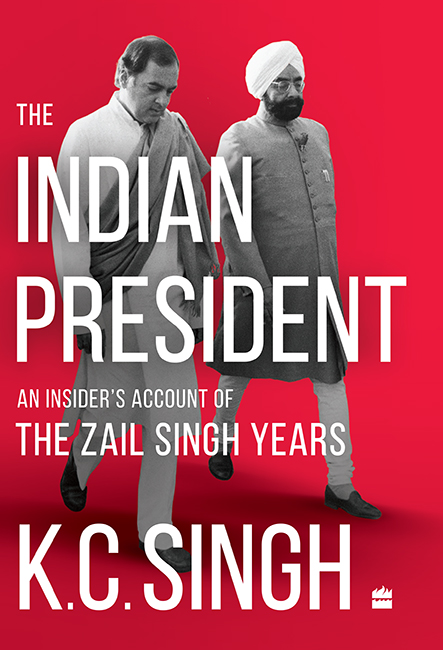

K.C. Singh - The Indian President: An Insiders Account of the Zail Singh Years

Here you can read online K.C. Singh - The Indian President: An Insiders Account of the Zail Singh Years full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2023, publisher: HarperCollins India, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

The Indian President: An Insiders Account of the Zail Singh Years: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Indian President: An Insiders Account of the Zail Singh Years" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

K.C. Singh: author's other books

Who wrote The Indian President: An Insiders Account of the Zail Singh Years? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Indian President: An Insiders Account of the Zail Singh Years — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Indian President: An Insiders Account of the Zail Singh Years" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

To my wife Vinu Singh and my sons for stoically bearing dislocations whenever I chose duty over expedience and honour over compromise

Contents

T HIS book on the president of India could have been written on at least three earlier occasions. The first was at the start of 1988 when I was posted as first secretary and deputy to the ambassador in the Indian embassy in Ankara. I had joined there after completing my nearly four-year deputation as deputy secretary to the president in July 1987. That is when President (Giani) Zail Singh concluded his controversy-laden presidency. I had got posted some months earlier, in routine, to Ankara, but left a couple months after my term ended.

Giani ji had managed to obtain a government residence from a by-then humbled Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. Till then, presidents had, after their terms ended, moved to their residences in their own states or other places they chose to spend their post-retirement life. President Neelam Sanjiva Reddy, President Singhs predecessor, had settled down at his farm at Anantapur. The convention to allot former presidents a residence in New Delhi was thus created. But Giani ji had no desire to vacate the national stage. Having a residence in Lutyens Delhi was a necessary precondition for that role. The Rajiv Gandhi government had survived the first half of 1987, as this book will describe, despite the Bofors controversy and a series of electoral defeats. The countrys politics was likely to be in flux, with Opposition parties that were knocked out in the 1984 Lok Sabha election getting a second wind.

Meanwhile, animus was building up in the prime ministers office (PMO) against me, something I was unaware of. I was singled out as the advisor whom Giani ji most trusted. I was also seen as complicit in the presidential defiance of the contemptuous treatment he received at the hands of the prime minister, his party functionaries and Congress governments. My posting orders in the Indian embassy in Ankara showed my local rank as that of a counsellor, even though my promotion as director, the equivalent position at headquarters, was some months away.

The assumption was that because hardly any supersessions occurred at that level, officers should be shown locally as having the higher rank to enable them to meet higher-level counterparts in other missions right from the beginning of their tenure. Diplomats in missions generally receive their counterparts from other missions one rank below or above them. Thus, a counsellor would get access to every number two in any mission, as even in the bigger missions the deputy heads, at best, would be ministers, just above a counsellor.

Sometime in January 1988, my former batchmate from the Indian Foreign Service (IFS), the late Firdaus Khargamwala, called me from Bahrain. He had resigned from service after his Japan posting, wishing to marry a Japanese lady after divorcing his charming Parsi wife. He had commenced a new career as a journalist and was, in 1988, the Gulf correspondent for The Hindu, based in Bahrain. He sent me a copy of a story in the Sunday magazine, which carried my alleged conversations with Congress politician Arjun Singh. The magazine said that this was proof of political machinations by the former president to overthrow the Rajiv Gandhi government. This happened a few days after I heard whispers that my promotion to director, equivalent to counsellor, as explained, had been withheld. The Ministry of External Affairs does not inform anyone who is not promoted, leaving those superseded to deduce the outcome if their name is not among the list of promotees.

The details of this episode involving my interaction with Arjun Singh will be related in a subsequent chapter. But the immediate consequences were as follows. I asked the ministry to post me back home so that I could put in my papers. Indian diplomats are not allowed to resign while on a posting abroad. This policy had been created to keep Indian officers and staff from seeking local employment or sponsorship and abandoning their job. The calculation was that if forced to return to India before quitting, the employees link with local sponsors may be weakened, perhaps also causing them to rethink the resignation.

In the months that followed, I moved my wife and two sons to Chandigarh, where the children were admitted to Yadavindra Public School. They had to abandon their elite schools without much notice. The elder one was going to an American school at the countrys Incirlik air base near Ankara. The younger one went to a British school. It was across a small valley, on one edge of which was the Indian embassy and the ambassadors residence.

My logic in opting to quit rather than go to the Central Administrative Tribunal was that my supersession was for political reasons, and thus, required a political response. My reports had been written by the president and could not be downgraded even by the prime minister. Therefore, to supersede me, the government chose the excuse that I had been actively engaged in soliciting the support of senior Congress leaders to overthrow the government. The story was, in fact, more complex than just this encapsulation may convey.

I awaited my posting back to the headquarters, which was processed, and took a few months to come through. Simultaneously, as is the normal procedure, names from the batch below me were taken up for promotion to the director level. While putting up their names to the Appointments Committee of the Cabinet, names of officers of earlier batches who had been superseded are also resubmitted. An urgent message arrived from the headquarters that they wanted my latest confidential report, written by the ambassador and my current boss, V.K. Grover. I found the ambassador rather stressed over this. We got along well, but he would hardly have given me flying colours, knowing that the prime minister himself was upset with me. I settled his dilemma, suggesting he reply that I was unwilling to submit the forms as I had already told the ministry that I wished to resign. Why, then, would I desire a fresh report to be written for my less than one years work at the embassy?

However, destiny wished to lead me down a different path. Before I could return to Delhi and resign, two things happened. One, Prime Minister Gandhi decided to visit Turkey in mid-1988. The ambassador could hardly relieve me without a substitute. I helped handle that visit, mostly staying out of the prime ministers path. In fact, I took charge of the accompanying media team, which, in those days, used to be a large contingent. After the successful visit, the ambassador decided that I should stay on till my successor arrived. The second development was interesting. I was informed by the headquarters that I had been promoted to the counsellors grade. My wife and sons were able to revisit Ankara, at my expense, now that the tension of the stand-off over the promotion was over. I eventually returned to the headquarters in the beginning of 1989.

After spending a couple of months on leave in Chandigarh, I reported to Joint Secretary in Charge of Administration Rajan Rathore. I had known him well since we had both been posted in New York in the early 1980s. He offered me the post of director (Africa) under a hard taskmaster, Arundhati Ghosh, who was known not to suffer fools. Apparently, no one was rushing to take up the post. Perhaps, in their wisdom, the ministry thought I would fit the bill, having just waded through a much nastier political quagmire. But before I joined, I was asked to see Foreign Secretary S.K. Singh, who received me with a direct question:

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Indian President: An Insiders Account of the Zail Singh Years»

Look at similar books to The Indian President: An Insiders Account of the Zail Singh Years. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Indian President: An Insiders Account of the Zail Singh Years and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.