Table of Contents

This is number one hundred and ninety-nine

in the second numbered series of the

Miegunyah Volumes

made possible by the

Miegunyah Fund

established by bequests

under the wills of

Sir Russell and Lady Grimwade.

Miegunyah was Russell Grimwades home

from 1911 to 1955

and Mab Grimwades home

from 1911 to 1973.

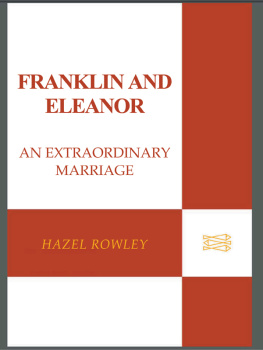

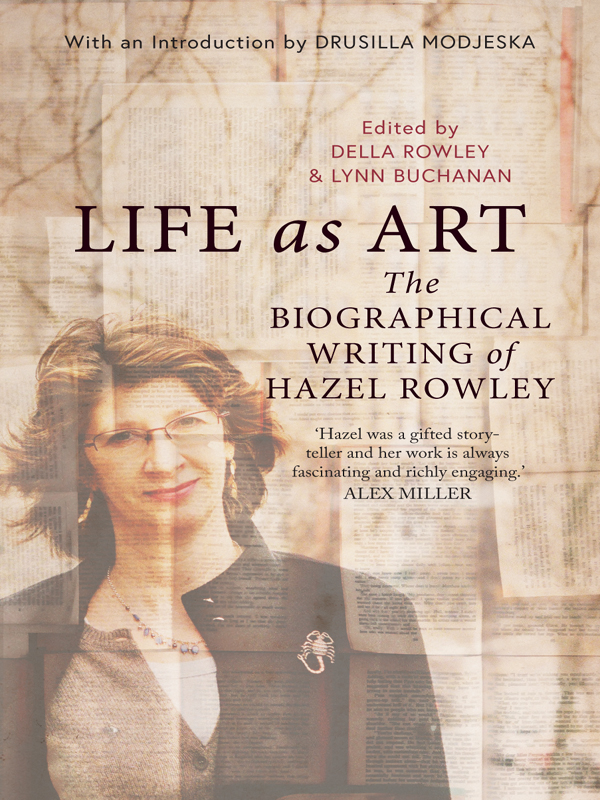

Della Rowley is Hazel Rowleys younger sister and literary executor. She lives in Adelaide, where she and Hazel grew up. Della was fortunate to experience Hazels wonderful imagination and inspirational energy and talent.

Lynn Buchanan was a close friend of Hazels for thirty years. She shared many conversations with Hazel on the joys and despairs of writing biography.

Della and Lynn, along with Hazels friend Irene Tomaszewski, established the Hazel Rowley Literary Fellowship in her memory.

LIFE as ART

The

BIOGRAPHICAL

WRITING of

HAZEL ROWLEY

Edited by

DELLA ROWLEY

& LYNN BUCHANAN

THE MIEGUNYAH PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

Level 1, 715 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

www.mup.com.au

First published 2021

Collection copyright Della Rowley and Lynn Buchanan

Text copyright Drusilla Modjeska, Hazel Rowley

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2021

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Photos reproduced with permission:

Cover photograph: Hazel Rowley in New York, courtesy Mathieu Bourgois.

p. vii: | Hazel Rowley, courtesy Isabel Hight. |

p. 93: | Portrait of Christina Stead, 1940s. National Library of Australia. |

p. 137: | Portrait of Richard Wright, 1943, photograph by Gordon Parks. Library of Congress. |

p. 175: | Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre take tea together, photograph by David E Scherman/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images. |

p. 205: | President Franklin D. Roosevelt and wife Eleanor Roosevelt, 1941. Photo by Fotosearch/Getty images. |

Typeset in Sabon 11/15.5 pt by Cannon Typesetting

Cover design by Nada Backovic

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

9780522877816 (paperback)

9780522877823 (ebook)

Contents

Biography is about freedom

it shows us infinite possibilities.

Its about choices in life.

Hazel Rowley

Introduction

Drusilla Modjeska

A T THE HEART OF BIOGRAPHY is a paradox. A biography is not a life, Hazel Rowley writes in the prologue to Christina Stead; lives cannot be recovered. And yet that, in some measure, is exactly what the biographer must do: if not recover, then re-imagine, re-envision a lived life with all its mess and contingency into a pattern of words, a narrative, a book we can hold in our hands.

Life as art.

No one knew better than Stead, Rowley continues, that life itself is a narrative. As a writer of novels that mined her life, and the lives around her, Christina Stead well knew the power of storiesthose we hear and those we tell, the versions and the detours, the truths, the mis-truths, the ocean of storyas Christina Stead put itin which we all live and breathe and shape our being. Turning life into story is one of humanitys enduring pleasures, Rowley concludes the prologue to this, her first biography. Stead may not even have been aware of the paradox when she wrote: The true portrait of a person should be built up as a painter builds it, with hints from everyone, brush-strokes, thousands of little touches.

As a child in the 1950s, Hazel Rowley loved stories. She loved reading them, she loved telling them, and at a remarkably young age she realised that the writers of the books she read had their own storieslike the Bront sisters in their Yorkshire vicaragethat were as magical and absorbing as the stories they wrote. By the age of nine, she had determined on becoming a writer.

It is the origin story of a biographer, and one I recognised when I met Hazel Rowley for the first time in the early 1980s. We were both living in Sydney, we were both finishing post-graduate studies. I was writing about the women novelists of Christina Steads generation whounlike Steadhad stayed in Australia. Hazel was recently back from Paris where shed been writing a thesis on Simone de Beauvoir and Violette Leduc. A decade after the heady arrival of second-wave feminism, we were both trying to make sense of our own lives and ambitions; I remember being deeply impressed that Hazel had the verve to go straight to the heart of the matter, so to speakto Simone de Beauvoir, one of the great pillars on which feminism standsthe woman, the figure, who taught us that we were not born women, we learned to become the women society would have us be. Our lives, our stories, were ours to shape. Or were they?

Hazel had interviewed Beauvoir in Paris, and as it happens, I had recently interviewed Stead who was back in Australia after the fifty-year absence that made her the writer she was. Neither interview had turned out well, and it wouldnt be an exaggeration to say that we were both still reeling as we measured up to the fact that neither of these legendary figures had met our great hopes. It was a necessary lessonour heroes are (disappointingly) human, just like usand that is one of the most important starting points for a writer of lives. Not to judge, as Hazel says again and again in these essays, but to understand. We could laugh about it later, realising how besieged they were by all us eager young feminists with our deeply meaningful questions. But at the time it was a blow. As Hazel describes, Beauvoir gave the most perfunctory answers, as if by rote, to the questions shed prepared with such care. Rather than help her see through, or beneath, the contentious swirl of stories that surrounded her, Beauvoir shored them up, curator of her own mythology. With me, Stead had been cranky and impatient. What a ridiculous question! Write your own book! At leastto my surprise, and unlike Beauvoir with HazelStead poured us a drink as I packed away my notes, and as she relaxed, she began to speak about her characters as if they were as alive and ferocious as she was. I never did get an answer to what gave her the courage to leave Sydney at the age of twenty-five in a steerage berth on the SS Oronsay; I never believed the Alone of For Love Alone, the novel that gives that journey its own mythic proportions. For an answer Id have to wait for Hazels biography.