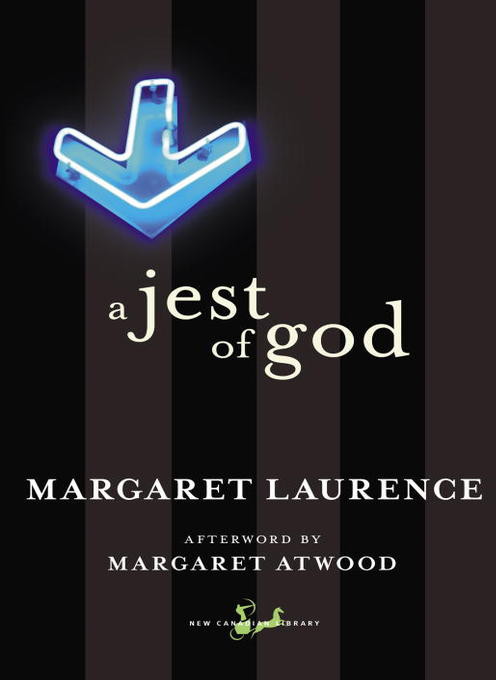

THE AUTHOR

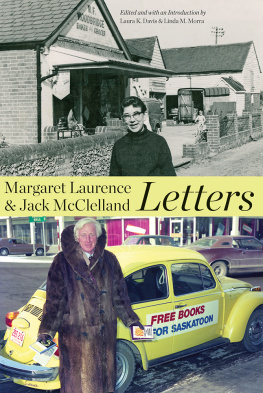

MARGARET LAURENCE was born in Neepawa, Manitoba, in 1926. Upon graduation from Winnipegs United College in 1947, she took a job as a reporter for the Winnipeg Citizen.

From 1950 until 1957 Laurence lived in Africa, the first two years in Somalia, the next five in Ghana, where her husband, a civil engineer, was working. She translated Somali poetry and prose during this time, and began her career as a fiction writer with stories set in Africa.

When Laurence returned to Canada in 1957, she settled in Vancouver, where she devoted herself to fiction with a Ghanaian setting: in her first novel, This Side Jordan, and in her first collection of short fiction, The Tomorrow-Tamer. Her two years in Somalia were the subject of her memoir, The Prophets Camel Bell.

Separating from her husband in 1962, Laurence moved to England, which became her home for a decade, the time she devoted to the creation of five books about the fictional town of Manawaka, patterned after her birthplace, and its people: The Stone Angel, A Jest of God, The Fire-Dwellers, A Bird in the House, and The Diviners.

Laurence settled in Lakefield, Ontario, in 1974. She complemented her fiction with essays, book reviews, and four childrens books. Her many honours include two Governor Generals Awards for Fiction and more than a dozen honorary degrees.

Margaret Laurence died in Lakefield, Ontario, in 1987.

THE NEW CANADIAN LIBRARY

General Editor: David Staines

ADVISORY BOARD

Alice Munro

W.H. New

Guy Vanderhaeghe

If I should pass the tomb of Jonah

I would stop there and sit for awhile;

Because I was swallowed one time deep in the dark

And came out alive after all.

Carl Sandburg, Losers

ONE

The wind blows low, the wind blows high

The snow comes falling from the sky,

Rachel Cameron says shell die

For the want of the golden city.

She is handsome, she is pretty,

She is the queen of the golden city

T hey are not actually chanting my name, of course. I only hear it that way from where I am watching at the classroom window, because I remember myself skipping rope to that song when I was about the age of the little girls out there now. Twenty-seven years ago, which seems impossible, and myself seven, but the same brown brick building, only a new wing added and the place smartened up. It would certainly have surprised me then to know Id end up here, in this room, no longer the one who was scared of not pleasing, but the thin giant She behind the desk at the front, the one with the power of picking any coloured chalk out of the box and writing anything at all on the blackboard. It seemed a power worth possessing, then.

Spanish dancers, turn around,

Spanish dancers, get out of this town.

People forget the songs, later on, but the knowledge of them must be passed like a secret language from child to child how far back? They seem like a different race, a separate species, all those generations of children. As though they must still exist somewhere, even after their bodies have grown grotesque, and they have forgotten the words and tunes, and learned disappointment, and finally died, the last dried shell of them painted and prettified for decent burial by mortal men like Niall Cameron, my father. Stupid thought. Morbid. I mustnt give houseroom in my skull to that sort of thing. Its dangerous to let yourself. I know that.

Nebuchadnezzar, King of the Jews,

Sold his wife for a pair of shoes.

I can imagine that one going back and back, through time and languages. Chanted in Latin, maybe, the same high sing-song voices, smug little Roman girls safe inside some villa in Gaul or Britain, skipping rope on a mosaic courtyard, not knowing the blue-painted dogmen were snarling outside the walls, stealthily learning. There. I am doing it again. This must stop. It isnt good for me. Whenever I find myself thinking in a brooding way, I must simply turn it off and think of something else. God forbid that I should turn into an eccentric. This isnt just imagination. Ive seen it happen. Not only teachers, of course, and not only women who havent married. Widows can become extremely odd as well, but at least they have the excuse of grief.

I dont have to concern myself yet for a while, surely. Thirty-four is still quite young. But now is the time to watch out for it.

The bell rings for end of recess. Quickly, I have to gather my children in. I must stop referring to them as my children, even to myself. It wont do. We all say it, of course. Even Calla says of the Grade Fives, Want to see the poster my kids painted today? But the words are no threat to her. She feels only a rough amused affection and irritation towards any or all of them, equally.

Come along, Grade Twos. Line up quietly now.

Am I beginning to talk in that simper tone, the one so many grade school teachers pick up without realizing? At first they only talk to the children like that, but it takes root and soon they cant speak any other way to anyone. Sapphire Travis does it all the time. Rachel, dear, would you be a very very good girl and pour me a weeny cup of tea? Poor Grade Ones. How do they endure it? Children have built-in radar to detect falseness.

Come along, now. We havent got all day. James, for goodness sake, stop dawdling.

Now Ive spoken more sharply than necessary. I have to watch this, too. Its hard to strike a balance. Its so often James I speak to like this, fearing to be too much the other way with him.

Why didnt I put my coat on, to come out? The spring wind is making me shiver. My arms, wrapped around myself for warmth, seem so long and skinny. The days are fine and mild lately, but the wind is still northern and knifing. Im susceptible to colds, and when I get one it hangs on and on, and really pulls me down.

James is the very last inside, as usual. That boy is the slowest thing on two feet when hes going into the room. Leaving, he always seems about to take off like a sparrow and miraculously fly. Looking at his wiry slightness, his ruffian sorrel hair, I feel an exasperated tenderness. I wonder why I should feel differently towards him? Because hes unique, thats why. I oughtnt to feel that way. They are all unique. What a pious sentiment, one which Willard Siddley would endorse. Certainly theyre all unique, but like the animals equality, some are more unique than others.

Calla Mackie is in the hall as I go in. I shouldnt try to avoid her eyes. Shes kind and well-meaning. If only she looked a little more usual, and didnt trot off twice a week to that fantastic Tabernacle. She bears down, through the noisy shoal of youngsters pushing upstairs like fish compelled upstream. Calla is stockily built, not fat at all but solid and broad. She says she ought to have been Ukrainian, and in fact she has that Slavic squareness and strong heavy bones. Her hair is greying and straight, and she cuts it herself with nail scissors. Ill bet shes never even set foot inside a hairdressers. She combs it back behind her ears but chops it into a fringe like a Shetland ponys over her forehead. She wears long-sleeved smocks for school, not for neatness but so she can wear the same brown tweed skirt and that dull-green bulky-knit sweater of hers, day after day without anyone noticing. Maybe she washes the sweater in the evenings from time to time, and dries it on the radiator in her flat. I wouldnt know. She drenches herself with Lemon Verbena cologne. Her smock today is the fawn chintz that looks like the kitchen curtains. Well, poor Calla it isnt her fault that she has no dress sense. I look quite smart in comparison.