Diversion Books

A Division of Diversion Publishing Corp.

80 Fifth Avenue, Suite 1101

New York, New York 10011

www.diversionbooks.com

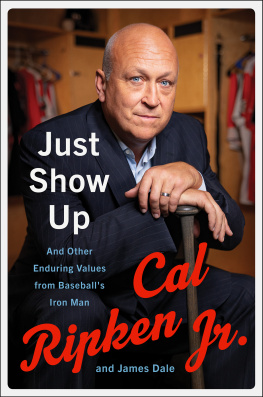

Copyright 1999 by Cal Ripken, Sr.

Foreword Cal Ripken, Jr.

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For more information, email info@diversionbooks.com.

First Diversion Books edition July 2010.

ISBN: 978-0-9829050-2-9 (ebook)

To my wife, Vi; daughter, Ellen; and sons,

Cal, Jr.; Fred; and Bill.

The closeness of family while traveling all over the

country made the game of life and the game of

baseball so great.

C.R.

With love to Beth, Casey, Maddie, and Charlie.

L.B.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

Let me start by thanking my dad. He inspired me with his commitment to the Oriole tradition and made me understand the importance of it. He not only taught me the fundamentals of baseball, but he also taught me to play it the right way, and to play it the Oriole way. From the very beginning, my dad let me know how important it was to be there for your team and to be counted on by your teammates.

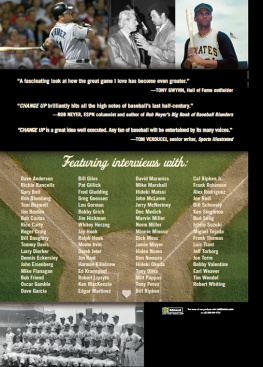

Those are my words, from the speech I made on September 6, 1995, at Baltimore's Camden Yards, after I had broken Lou Gehrig's record by playing in my 2,131st consecutive game. I paid tribute to a number of people that night, but I started with my dad because, well, that's where the Streak, which ended in 1998 at 2,632 games, really started.

Would there have been a streak had it not been for the lessons of discipline, dedication, determination, and desire that my father taught me? Heck, there might not have been a career were it not for my dad. There might not even have been a big-league appearance.

I probably had the talent, genetically speaking, to be a pretty good baseball player. I most likely would've had enough ability to get drafted, but beyond that I could very well have been a statistic, like most minor leaguersabout three percent of whom actually make it to the majors. Without Dad's influence I might not have made it all. I almost surely wouldn't have had the career that I've had. I certainly wouldn't have had the desire to be in the lineup every day, or understand the importance of that.

Dad impressed upon me from the beginning that in order to do anything well, you have to work at it. And in order to work at something you have to really love it and understand the value and the product of your work. Obviously, in baseball, you have to have the talent first, but once you have the talent the thing that makes you betterin baseball or in anything you dois hard work. That lesson was the biggest and best gift that my dad gave me. He also gave me his passion for the sport, the great feeling of wearing the uniform, his love of the game, his willingness to work at everything he did, and his satisfaction in the rewards of that work. I came to understand and appreciate all of those things at a very early age.

You can't truly understand it all unless you're willing to work. You have to be willing to lay it on the line first. But once you do, there's a very complete and satisfying feeling, and nobody can take that away from you. Without my father's influence, though, without that real strong guidance, I probably would've washed out of baseball eventually. The funny thing is, as valuable as these lessons were, I don't think Dad even knew he was giving them to me, because he wasn't teaching me directly, he was simply showing it all to me by being himself.

My dad has always been a great teacher of the game of baseball. He does that with words and demonstrations, almost like a teacher in a classroom would. But many of the big things I learned from himin baseball and in lifeI learned just by watching him. For instance, you can speak of a work ethic, but how do you really teach that? The only way you get it across is by showing it, by living it.

And that's how my father has lived his life, how he has gone about doing things: his routines, the way he dives in, organizes and just attacks any kind of work, his ability to identify the things that need to be done and do them. He's a real hands-on doer in all facets of his life.

I've always been willing to work hard to get better in baseball, and I'm willing to do that in most areas of my life. My dad is the same waythat's his personality, that's what he does. And I really picked up on that.

When the Orioles moved to a new spring training site, they needed to decide how to set up the ball fields, where the dormitory was going to go, and so forth. Dad always took on the problems and became the foreman of the job, but he was also out there doing the work, too. He'd actually be digging out fields, measuring the bases, cutting the diamond, leveling the infield, putting down the grass seed, pouring the concrete for the dugouts, and putting the backstops up.

That's so typical of him. When the Orioles moved their spring training camp from Fernandina Beach, north of Jacksonville, to Biscayne College (which is now St. Thomas University) in the Miami suburb of Opa-Locka, Dad supervised the construction crew and did a lot of the work himself. This was all while spring training was going on, and he was running the camp at the same time! He'd be a baseball guy during the daystarting with his morning meetings and all the way through to the game or whatever activities ended the dayand then he'd go to work on the construction job. He wouldn't even take his uniform off, he'd just take a little time to eat a bit of a sandwich or something and then jump on the tractor. Sometimes he'd work so long that he had to turn on the tractor's headlights.

People can talk about work ethic, but the more they talk about it, the less they do. My dad's not a talker, he's a doer. So I just watched him, and that's how I found out how to do the right thing. I learned that if I wanted something done the right way, and I wanted it done to my own high standards, only I could do it. And I think that's a great, great trait.

He passed on his love of baseball to me in the same way: by example. As a kid I had a chance to witness it by going to the ballpark with him and being in his environment. Sometimes, at home, it could seem a little like a business. He had a lot of administrative responsibilities, such as typing out paperwork for the organization. He was required to file daily reports on each player, in triplicate, and include the box score from the local newspaper. I still remember Old One-Finger, as Mom called him, pecking away on that Smith-Corona. He didn't have as much time to play with us as he would've liked, but we could see his joy for sports when we had the opportunity.

When I had a chance to ride in the car with him to the ballpark, I could see his whole world open up. I wouldn't call it a personality change, but once Dad put that uniform on, there was this comfort, this joy, this passion for who he was and what he was doing that was just a great thing to see. He used to say, There's something to putting this uniform on. These are my work clothes. And he really meant it.

The first thing he did when he got to the ballpark was put that uniform on, and he did it very quickly. When he walked through the door there was no BS'ing, there was no walking around being sociable. He put the uniform on, then the day started. The last thing he did before he went home was take it off. But at the end of the day it was difficult to get that uniform off his body he didn't want to take it off.

That's the kind of love for baseball that I took from being around my father. I discovered it for myself, by being around him, and then I started to feel the same thing. He never preached it, I just watched him and I saw it. It was almost like he had a secret that the rest of us didn't know, and I was curious to find out what that secret was.

Next page