and heres the pitch. Theres a sharply hit ground

ball to second Geoffrey Wills got it

Theres a lot of stuff goes on.

As they were making their involuntary departure from the Garden of Eden, Adam remarked to Eve (or so it is said), Darling, we live in an age of transition. Of course, everyone everywhere always lives in such an age because change is lifes only constant. That has certainly been true of the nice slice of American life that is Major League Baseball (MLB).

In the twenty years since the first publication of this book, baseball has experienced many exhilarating improvements and some disorienting and dispiriting turbulence. Through it all, however, baseball has remained a gift that keeps on giving because it never stops surprising, intriguing and challenging its attentive fans. Its steadily thickening sediment of statistics and other layers of history invite fresh comparisons of contemporary players and their achievements with those of previous generations. And for baseball fans, who must be the most argumentative Americans, comparisons entail controversies, which are integral to the vibrant life of the game off the field and around the calendar. Furthermore, baseball retains its remarkable capacity for evolving new subtleties pertinent to the related skills of assembling a team and playing the game. And even in baseballs third century, it has a beguiling ability to generate enchanting new quirks. Consider this actual event from a minor-league game: a team hit into a triple play without the ball ever being touched by a fielder. How? Think about it. But while thinking, read on. You will find the answer at the end of this introduction.

The continuing interest in this book twenty years after it was published is a tribute to baseballs rich traditions and fascinating craftsmanship, and to the literacyand numeracyof baseball fans, who have an unslakable thirst for writings about the game. I am one of those fans, and in 1987 I wanted to read a book that, I discovered, had not been written.

As a columnist preoccupied with politics and cultural matters, my purpose in writing, more often than not, is less to say what I think about a particular subject than it is to find out what I think about that subject. As an amateur student of baseball, I wrote this book during the 1988 and 1989 seasons, not to say what I knew about baseballwhich, I soon discovered, was not muchbut rather because no one had written it for me. I knew that, in the words of Tony La Russa that serve as this books epigraph, Theres a lot of stuff goes on out there, during a game. I, however, could not see it.

Baseball, with the largest field of play of any sport other than polo, is the most observable of team games. The playersat most thirteen at any moment (and there are that many only when the bases are loaded)are dispersed across a large and visually soothing green field. One can, however, observe something, be it politics or art or opera or baseball, without comprehending it. Like a novice visitor to a museum or cathedral, I needed a baseball docent.

Actually, I decided I needed four of them. Hitting, pitching, fielding and managing are the four basic elements of baseball competition. So in the winter months after the 1987 season, I set about deciding which four people would best serve to illuminate the four crafts and finding out if they would have the time and patience to do so.

Luck is an inexpugnable element of athletic competition; it was also a large factor in the creation of this book. It was my great good fortune that, as the 1988 season approached, baseball boasted four young, able, thoughtful, articulate and cooperative practitioners. Three were players still early in what then seemed to be promising careers. The fourth was a manager early in what has turned out to be a prodigious career.

Before 1988, Tony Gwynn, having completed the sixth of what would be his twenty seasons, had appeared in only 769 of the 2,440 games he would play. In 1984 and 1987 he had won two of what would be his eight National League batting titles. Cal Ripken had played 992 games, less than a third of his career total of 3,001, but of those 992, he already was inhere was a harbinger of something biga consecutive-games streak of 927. In the winter of 19871988 Orel Hershiser was preparing for the sixth of what would be eighteen major-league seasons. His record with the 1987 Dodgers was 1616, but the Dodgers owner, Peter OMalley strongly recommended that I make Hershiser my subject. How right he was.

Gwynn and Ripken entered the Hall of Fame together in 2007. On induction day, the village of Cooperstown (population 2,300) had 75,000 visitors. At 4 p.m., immediately after the ceremony, I started my car, intending to drive back to Washington. Silly me. After sitting for two hours in congealed traffic a few yards from the Cooperstown Inn, where I had spent the previous two nights, I checked back into the Inn for another night. Six years into their retirements as players, Gwynn and Ripken could still draw a crowd. It was a satisfying inconvenience.

Today, Gwynn is head baseball coach at San Diego State University, where he was a basketball as well as baseball star. SDSU is a few miles from PETCO Park, the Padres new ballpark. He never played there, but another Tony Gwynn, his son, now is, as his father was, a Padres outfielder. Ripken has become a baseball entrepreneur. His many youth-baseball enterprises are countering the recent tendency of other sports, such as soccer and lacrosse, to poach young talent that belongs, or so I think, in baseball. Gwynn and Ripken, who gave fans so many imperishable memories, are now transmitting the culture of the game to a rising generation of players.

Hershiser had an excellent career, with 204 wins, 150 losses and an earned run average (ERA) of 3.48. His record was not luminous enough to earn him a place in the Hall of Fame, but it did include many good years and one of transcendent greatness. As luck would have it, that year was 1988, when he won the National League Cy Young Award with a 238 record and a 2.26 ERA. He set a record that still stands of fifty-nine consecutive scoreless innings and was the MVP of the World Series as he led the Dodgers to defeat Tony La Russas Oakland As. From this grateful authors point of view, Hershiser saved his best for exactly the right season. Today, ESPN viewers get the benefit of Hershisers always-acute and often-acerbic baseball analysis. His is sports commentary for grown-ups.

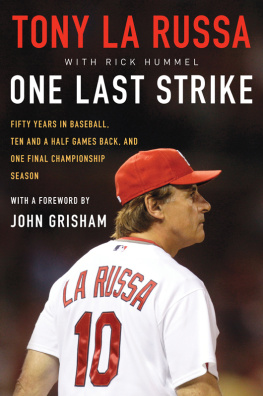

My books fourth subject is still a man at work. After the 1987 season, La Russas ninth in a major-league dugout, he was a manager who, at forty-three, was still young relative to many of his peers. Nineteen of the other twenty-six managers were older. La Russa then ranked sixty-fourth all-time in games managed (1,276) and sixty-first in wins (648). By the end of the 2009 season, he ranked third in games managed (4,772), third in games won (2,552), and second in games lost (2,217). It is certain that La Russa will, in due time, have a bronze plaque in Cooperstown. By then, if he chooses, he will have surpassed John McGraws total of 2,763 wins as a manager.

He might choose not to. Chatting in the bowels of Nationals Park in Washington, D.C., on a late July afternoon in 2009, La Russa told me that he did not care about surpassing McGraw. Perhaps he meant that. He may well have meant it that day because it was a tiresome Monday. The Cardinals, then in the thick of a hotly contested National League Central Division race, were in town for only one game, a makeup of a regularly scheduled game that had been rained out a few weeks earlier. It was going to be a miserably humidwhen it was not soggyWashington night of more rain and rain delays. Under baseballs unbalanced schedules, teams from one division are supposed to make only one visit to teams in other divisions, so umpires are reluctant to allow rain to cancel any interdivision games. Umpires would be especially reluctant to allow rain to cancel a one-game visit by a team trying to make up a previously rained-out game. La Russa knew that after rain delays and long after midnight the Cardinals would board a train for Philadelphia, where they would take the field not many hours after getting to bed early Tuesday morning.