Contents

Guide

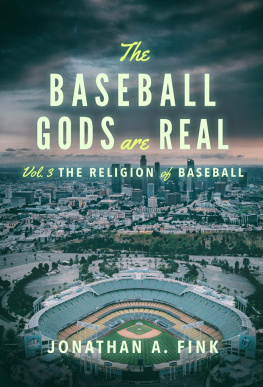

The Baseball 100

Joe Posnanski

ALSO BY JOE POSNANSKI

The Life and Afterlife of Harry Houdini

The Secret of Golf

Paterno

The Machine

The Soul of Baseball

To Margo, Elizabeth, and Katie

Introduction by George F. Will

B aseball fans are an argumentative tribe. Suppose (supposing is what those of us do who do not know, as Posnanski does, pretty much everything about baseballs history) there have been, say, two left-handed middle relievers from north central South Dakota. If so, this much is certain: Wherever two or more fans are gathered, there will be a heated dispute about who was the best of this cohort. This volume will ignite a splendid conflagration of arguments.

Do you agree with Joe Posnanski that Arky Vaughan is the least-known great player? If not, you also disagree with Bill James, who in his Baseball Historical Abstract said the two greatest 20th century shortstops were Honus Wagner and Vaughan. Posnanski says that Miguel Cabreras 2017 Triple Crown season was the most impressive of the 17 such seasons in Major League Baseball historybetter than Mickey Mantles in 1956 (.353 average, 52 home runs, 130 RBIs). Disagree? Game on.

Those of us who for many years have relished Posnanskis baseball writings have a question or two. First, how many Joe Posnanskis are there? If the answer is just one, our second question is: How old is he? Methuselah, the Bible tells us, lived 969 years. Posnanski must already have lived more than 200 years. How else could he have acquired such a stock of illuminating facts and entertaining stories about the rich history of this endlessly fascinating sport? He probably was there on June 19, 1846, when the 25-year-old Alexander Joy Cartwright, in a meadow by a pond in what is now the Murray Hill section of Manhattan, made one of the most important and durable decisions in human history: Cartwright decided that base balls (it was then a two-word noun) bases should be 90 feet apart.

We all know, and not just because John F. Kennedy famously said so, that life is unfair. But, really, it is simply not fair that Posnanski has had the opportunity to gather the material in the volume. Or that he has the talent to present it in such a delightful way. His book is a deep dive into the history of an institution woven into two centuries of a nation that soon will celebrate its 250th birthday.

This is emphatically not just a compilation of what is called, by the intellectually careless, baseball trivia. Leave aside the fact, which it is, that nothing about baseball is trivial. This book is, however, chock-full of fascinating facts. For example:

As a center fielder Tris Speaker made six unassisted double plays. Ichiro Suzuki led his league in singles 10 consecutive years and is the only person to have 200 singles in a season, which he did twice. The only player with at least 400 homers, 500 doubles, 1,500 RBIs, 1,500 runs, 300 stolen bases, and fewer than 50 caught stealing is Carlos Beltrn. Although Tony Gwynn was not a power hitter (135 career home runs), he was such a dangerous hitter he was intentionally walked 203 times, more than Ernie Banks (512 homers) or Mike Schmidt (548 homers). And for 19 consecutive seasons (19832001) Gwynn had more walks than strikeouts. He faced Greg Maddux 107 times and never struck out. Willie McCovey did something that neither Babe Ruth nor Lou Gehrig nor Barry Bonds didhit .300, score 100 runs, drive in 100 runs, and walk 100 times in seven consecutive seasons. Among all pitchers in the live-ball era, Robin Roberts allowed the fewest walks per nine innings. (Also, from 1952 through 1955, he completed 118 of his 154 starts.) Johnny Mize was 34 and just back from war when in 1947 he hit 51 home runs while striking out only 42 times.

It is often said that baseball has had only two distinct eras, the Deadball Era, which ended in 1920, and all the seasons that have come after it. (It would not be clarifying to dignify the PEDperformance-enhancing drugsparenthesis in baseballs history as an era.) This is, however, not quite accurate.

A new era began in the early afternoon of April 15, 1947, in the borough of Brooklyn, when Jackie Roosevelt Robinson trotted out to play first base in the top of the first inning against the Boston Braves. The long exclusion of breathtaking talent from the highest level of baseball competition began to end. Willie Mays, Frank Robinson, Ernie Banks, and others were coming. Pitching records compiled by those who did not have to face Josh Gibson and Cool Papa Bell must be considered with this in mind. As must the hitting achievements of those who never faced Satchel Paige.

So, this book is, among other fine things, a rendering of justice. Among his 100 finest players, Posnanski includes, never implausibly, some of the great stars of the Negro Leagues. One pleasant aspect of this is that it gives us refreshing relief from the tyranny of modern metrics. Because newspaper coverage of the Negro Leagues was often haphazard, and because of the sometimes improvisational nature of the schedules, and because exhibition and barnstorming games were important to the players careers, there is less statistical basis for making assessments. And that is, in a way, liberating. We must relyhow wonderfully anachronistic and quaint this ison the judgments of baseball people who actually saw the Negro Leagues stars.

If Casey Stengel thought Bullet Rogan was the best all-around player in the world, and perhaps the best pitcher who ever lived, that is good enough for Posnanski, and for me. When Honus Wagner, the greatest of all shortstops, was told that people were calling Pop Lloyd, the Negro Leagues star, the black Honus Wagner, he replied, It is a privilege to have been compared with him. Josh Gibson, said Bill Veeck, was, at a minimum, two Yogi Berras. Roy Campanella, whose race kept him out of Major League Baseball until he was 26, but who was arguably the best MLB catcher not named Johnny Bench, said Monte Irvin was the best all-around player I have ever seen. As great as he was in 1951 [when he was 32], he was twice that good 10 years earlier in the Negro Leagues.

Furthermore, Posnanski makes the following elegant point:

Henry Aaron was born in Mobile, Alabama, in 1934. Willie McCovey was born there four years later, six months before Billy Williams was born in the nearby town of Whistler. If, Posnanski writes, you ever find yourself wondering about the quality of the players in the Negro Leagues, think about this: If Aaron, Williams, and McCovey had been born 20 years earlier, all three of them would have spent their primes in the Negro Leagues, and their stories would be told as legend. People would be telling tall tales about the power of Stretch McCovey or the impossibly quick bat of Henry Aaron or the gorgeousness of Billy Williams hitting and would you believe it? I wouldnt worry about people overrating Negro Leaguers. Id worry about people underrating them.

I assume that this small sample of Posnanskis facts and judgments has whetted your appetite for the feast that awaits you in this book. I will stop here, so that I do not further delay the fun you are about to have.

Introduction

T his seems as good a time as any to tell you about my mother, Frances Posnanski, who came to the United States in 1964, less than three years before I was born. In her entire life, I suspect that my mother has not watched a complete inning of baseball. I dont mean in a row; Im talking cumulatively. I sincerely doubt that she has actually seen three baseball outs.