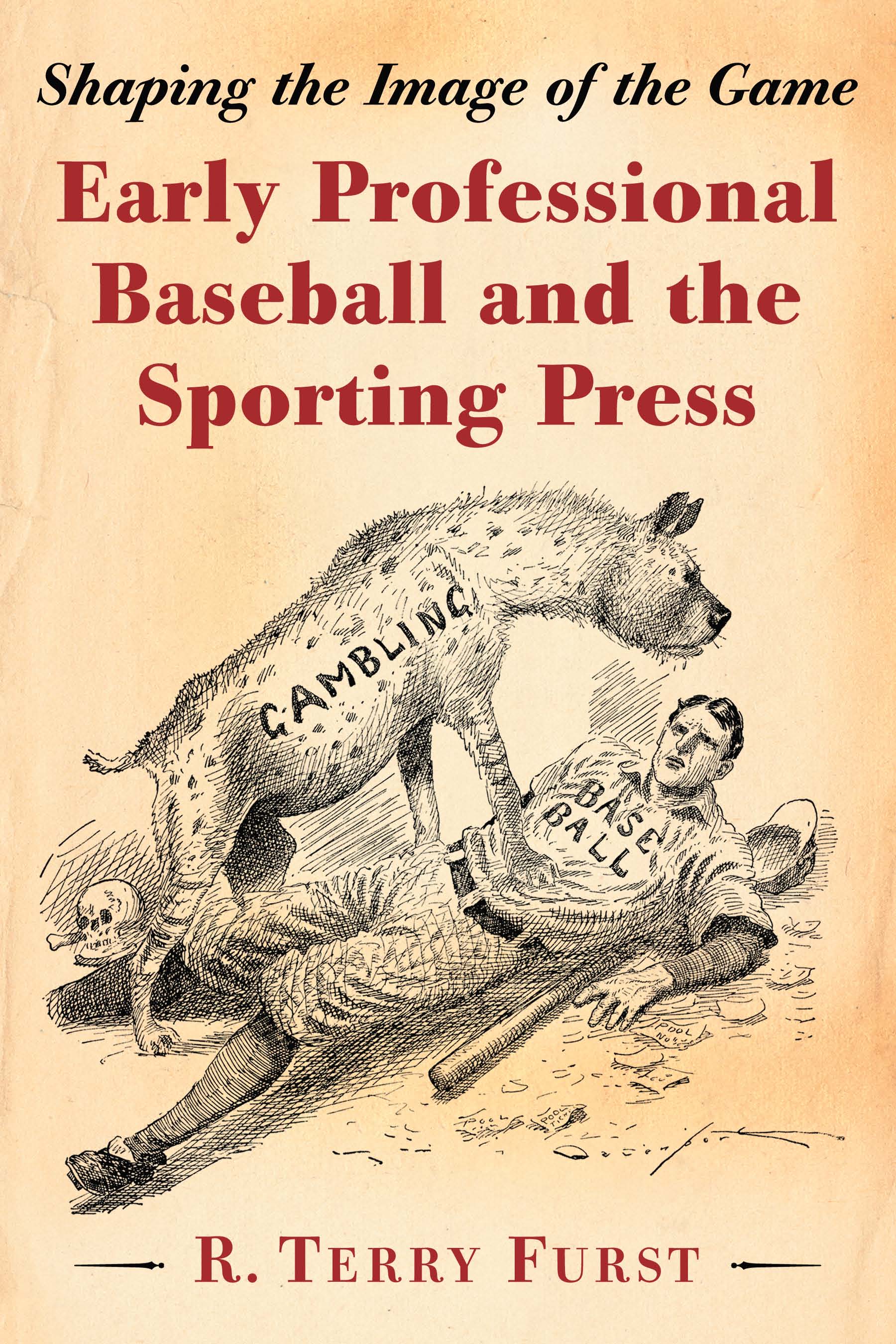

Early Professional Baseball and the Sporting Press

Shaping the Image of the Game

R. Terry Furst

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-0625-5

2014 R. Terry Furst. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Cover art: Homer Davenport, When Gambling Controlled, pen and ink cartoon, 16" 21"

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To Angela DiBello,

an irrepressible aesthete and inspiration

to all who know her.

Acknowledgments

This book greatly benefited from the contributions of the following people: Maria Reveron-Harrison, Avi Bornstein, Deeadra Brown, Laila Alsabahi, Diane Glynn, Dick Perez, John Thorn, and to the baseball and sport historians, past and present, whose work guided my path. The help of the librarians at the Rare Manuscript Division of the New York Public Library and the annex of the New York Public Library made my research effort an easier task than it might have been. Their help is greatly appreciated.

I deeply appreciate the help and encouragement of Edward Sagarin and Bernard Rosenberg of City College of New Yorktheir patient confidence in my work will be remembered. The book is dedicated to their memory.

Introduction

This book describes and analyzes the process by which the collective image of professional baseball was formed. It traces both the negation and the affirmation of ideas in the sport press that would impede or promote the growth of baseball from a recreational pastime to a spectator sport spectacle in mid-nineteenth-century America. The image grew as a result of a complex of factors. This complex included sports reportage and reading by the baseball public of matters in the sport press, discussion of baseball within social and occupational networks, game attendance and changing evaluations of work and play. These variables did not operate in a simple cause-and-effect relationship, with one variable determining the outcome of another. They combined in complex ways; changing values toward work and play both preserved and undermined sentiments toward baseball. Much of this interactive complex was influenced by the English sports ideal and newly formed attitudes toward recreational pursuits and sport in America.

The sport press was a necessary condition for the collective construction of knowledge about baseball. Therefore, this study traces sports reports of significant events in baseball (e.g., the Cincinnati Red Stockings tour of 1869) and describes the collective processes that helped engender the image of professional baseball. Editorial commentaries, evaluative descriptions, and letters to the editor are analyzed from the standpoint of sentiments toward the older and the emerging orientations toward playing baseball.

In its infancy, baseball adopted an attenuated English sports ideal, which is suggested by the playing rules, by-laws, and the social-recreational approach to playing baseball by clubs like the New York Knickerbockers and the Brooklyn Excelsiors. However, as a more competitive style of play grew in organized baseball, the domains of work and play grew closer together on the ball field, and they coalesced in the minds of the baseball public. Writing about the image of professional baseball in the 1960s, Roger Angell observes:

Baseball itself has the most enviable corporate image in the world. Its evocations and loyalties firmly planted in the mind of every American male during childhood and nurtured thereafter by millions of words of free newspaper publicity appear to be unassailable. It is the national pastime. It is youth, springtime, a trip to the country, part of our past.

Approximately a hundred years earlier the image of professional baseball was not firmly planted in the mind of every American male. Instead, there existed a composite of ideas about the game. Disparate notions of what the game of baseball was and should be awkwardly jostled each other and at times came into sharp conflict. The imprint of an older, social-recreational approach to playing baseball was coming into conflict with a newer, more competitive style of play.

Much written about baseball in the sport press reflected this conflict. In 1875 a sportswriter declared, As a general thing, any professional baseball club will throw a game if there is money in it. A horse race is a pretty safe thing to speculate on in comparison with an average baseball match. These strikingly dissimilar sentiments span a period of time in which the image of professional baseball was being formed. By the early 1870s, the attributes associated with the professional game had been set forth by the sport press as a loose configuration of characteristics that included skillful play, payment of salaries, disreputability of players, the recognition of the names of leading players, and an awareness of the clubs they represented.

But what is an image? Kenneth E. Boulding perceives an image as a loose structure, something like a molecule.

From this standpoint, baseball press reportage is assumed to be primarily responsible for shaping ideas about the image of professional baseball. However, the task is not without epistemological difficulties. One underlying problem can be put in the form of a question: Are the image of baseball and the socio-historical reality of baseball one and the same? No, they are not the same. Boulding takes up this thorny problem in a chapter titled The Image and Truth: Some Philosophical Implications. Newsprint stories provided a basis for people to imaginatively reconstruct events in baseball. These reconstructions were not necessarily isomorphic with the world of baseballthey were the world of baseball.

Helping to illuminate this world, writers used a lively prose style that helped to translate descriptions of the event into a new language that facilitated the imaginative or vicarious reconstruction of the reported event. Dramatic adjectives, scintillating verbs and colorful hyperbole enlivened baseball descriptions. Fly balls were hauled in, batters wielded the ash, teams that failed to score were skunked or calcimined. Baseball writing was a focal point for the organization of ideas about baseball. However, attendance at games, discussions of baseball matters and the omnipresence of changing attitudes toward work and play all helped to shape our knowledge of baseball.

To analyze ideas about baseball, I rely heavily on the press reports of baseball as historical data. I also treat these reports as representations of a sociological process and apply concepts such as status, deviance, class, and conspicuous leisure, among others, to analyze the process. This approach incorporates the distinctions noted by Cahnman and Boskoff, who point out the differences in the contrasting studies of revolutions by Crane Brinton and Lyford Edwards.

Paralleling the question of whether or not the image of professional baseball accurately reflects the socio-historical reality of baseball is the question of whether or not a terminological distinction should be made when referring to either the baseball player or organized baseball. These are separate conceptual entitiesthe latter denotes the various elements that constitute the organization of baseball, such as the structure of the National Association of Base Ball Players, the format of championships, and the stability of clubs within the association.

Next page