Table of Contents

From Bob, To Nancy

For Jane, Denley Ann and Brett and Jenny, Abby Jane and Niki and Neily

I, your servant, will build a mill which does not require water, but which is powered by wind alone.

LEONARDO DA VINCI

PROLOGUE

A PUBLIC MEETING

Democracy! Bah! When I hear thatI reach for my feather boa!

ALLEN GINSBERG

December 6, 2004 Marthas Vineyard Island, Massachusetts

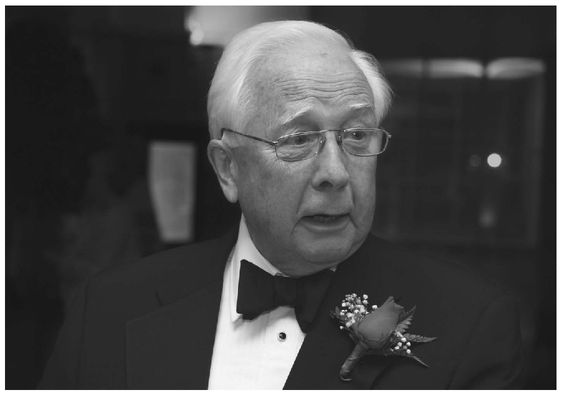

David McCulloughs face contorted with anger. Its outrageous! he yelled. He sounded like anyone but the mellow, well-measured man of letters who narrated tales of American history on national television. Indeed, the popular author sounded quite overwrought.

Nantucket Sound, he shouted, is hallowed ground. He had uttered that phrase before, as the narrator of Ken Burnss famous Civil War documentary aired on public television. This time, however, he was sounding his own battle cry, crowing his promotion to general in the seaside civil war, a war that had become an internationally watched conflict over the future of energy and of Americas air, coasts, and oceans.

On this late-fall evening, as the sky spit a chilly mixture of snow and sleet, McCulloughs big voice filled the high school auditorium lobby on Marthas Vineyard, an island favored by movie stars, politicians, the international jet set, authors, and other glitterati.

He continued his mini oration, This is a preservation issue. Its not an environmental issue.

McCullough, surrounded by a small circle of admirers, had just walked out of the first of a group of four public hearings called by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers regarding a proposal to build a large electrical-generation project in the middle of a body of water known as Nantucket Sound. Cape Wind Associates, a limited liability company, wanted to place a vast field of wind turbines out in the salt water. The turbines would, said the developers, produce enough clean electricity to satisfy a considerable proportion of Cape Cods needs. Indeed, on rare occasions, the project would supply all the necessary electricity, obviating the consumption of fossil fuels.

Over the three years the battle had raged, McCulloughs opposition to the project had become common knowledge around Cape Cod and the wealthy islands of Nantucket and Marthas Vineyard, in part because of a highly emotional radio advertisement he had recorded that excoriated the project.

Rarely, however, did McCullough appear at public meetings about the wind farm. Indeed, like so many of the beautiful people engineering the public show of fury over Cape Wind, the television star and author preferred controlled, closed-door situations. Tonight, though, after refusing a request for a formal interview, he sputtered on.

This is visual pollution, he complained. He was unable to stop talking. As he and his entourage departed the building, the sentences trailed after him, like leaves blowing in a high wind.

David McCullough voiced his opposition to Cape Wind from the earliest days of the seaside civil war.

Cape Wind, the brain child of a small group of innovative energy developers, first made headlines in the summer of 2001, only weeks before September 11. The first adamant public opposition surfaced less than a month after the World Trade Center disaster. Cape Wind president Jim Gordon, a fiercely driven and ardently independent man who had made millions during his thirty-year career as an energy entrepreneur, had initially proposed erecting 170 towering wind turbines five miles off the Capes southern coast. During the course of the battle, as offshore wind technology improved, the number of turbines had dropped to 130, but the output of the individual turbines had grown considerably, from 2.8 to 3.6 megawatts each. The projects resultant nameplate capacity would have been 468 megawatts, quite large for a wind farm. The projects typical output, however, would have been rather less, since wind turbines only rarely operate at full capacity.

Because Nantucket Sounds winds often blow best when electricity is needed most, during the frigid wintertime when fossil-fuel costs are high or on hot summer days when Cape Cods many 7,000-square-foot shoreline homes have their air conditioners pumping hard, an ocean-based wind farm seemed to Gordon an obvious solution to New Englands power-generation dilemma. Lacking indigenous fossil fuels, the region suffered extremely high electricity prices. Moreover, much of the regions electrical generation was aged, inefficient, and consequently highly polluting.

Because New Englands coastal regions are already so overdeveloped, little space remained for land-based wind projects. Building offshore seemed an obvious solution to the crisis. Nevertheless, Gordon, a wildcatter, had shocked the region by proposing the massive project. Although offshore wind had a successful ten-year history in Europe, the projects to date had been relatively small-scale. Nothing this ambitious had been built, although several proposed projects far exceeded the size suggested for Nantucket Sound.

Gordon was undeterred. Ebullient and confident, he believed his project would pay off financially while also cutting down on fossil-fuel emissions. From Gordons point of view, the region would be trading a small area of the ocean, used mostly for recreational sailing and saltwater fishing, for cleaner air and a leadership role in clean-energy innovation.

Cape Cods powerful elite saw things differently. To them, Gordon and his team were interlopers. The same winds that had enticed Gordon to gamble his millions had, as early as the nineteenth century, enticed large flocks of the wealthy to nest along the Capes hitherto rather neglected southern shoreline. By the time Cape Wind made headlines, the area of Cape Cod, Nantucket, and Marthas Vineyard had become a devils triangle of entrenched, often inherited, wealth. Those seashore homeowners had come to see Nantucket Sound as their very own playground.

Few Americans will ever literally see Nantucket Sound. Most of its beaches are intentionally closed to the public, who are instead directed further toward Cape Cods eastern end, to the national seashore that overlooks the Atlantic Ocean. Still, many Americans have seen Nantucket Sound on television. These are the waters enjoyed by Jack and Jackie Kennedy, who sailed out from the summer capital of their brief CamelotHyannisport. The carefully orchestrated, nationally broadcast images showing the romantic young couple sailing their elegant little boat across the glittering waves brought about the end of quaint Cape Cod. Already drowning in money, the southern shoreline, now made famous by the Kennedy family, was swamped by a storm-surge of development.

Today, much of Cape Cod is a highly commercial, Disneyesque version of what was once a very lovely seaside area. Along the south shore and on Marthas Vineyard and Nantucket, colonies of the rich and the hyperrich flourish as never beforenot just multimillion-dollar folk, but