It is the history of our kindnesses that alone makes this world tolerable. If it were not for that, for the effect of kind words, kind looks, kind letters, multiplying, spreading, making one happy through another and bringing forth benefits, some thirty, some fifty, some a thousandfold, I should be tempted to think our life a practical jest in the worst possible spirit.

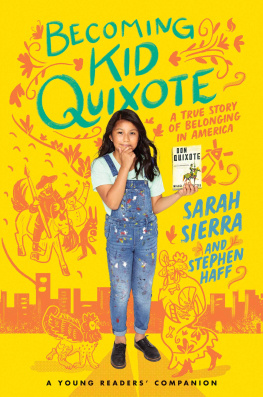

Thats a big book, says Felicity. Her eyes are impossibly wide, made for seeing everything around her.

Yes, I answer.

Were going to read this? she asks. At eight years old, she has never seen a book this big aside from the Bible in church. She is tiny and barely reaches my elbow as we sit side by side.

Yes, and were going to translate the whole thing. Its going to take five years.

Whoa.

Open it up.

All of the kids open their copies. There are twenty-five students, aged six to fifteen, all sitting around the same table, facing each other.

What are these words? asks Felicity. Is this Spanish?

Yes. Four-hundred-year-old Spanish.

I cant read Spanish.

How many people here can read Spanish? I ask the group.

Hands go up: about half the kids, mostly the teenagers. Percy, barely seven years old, also raises his hand, as does Rebecca, aged eleven.

Dont worry, Felicity. See? All of these people can help you. Plus, you know how to speak and understand spoken Spanish at home with your family just like everyone here except me, so you have an advantage.

Do you know how to read Spanish? she asks me.

I know the words that your parents are teaching me, and I can use my knowledge of Latin to guess. As you know, Latin is the mother of Spanish. Im excited to learn more, right beside you.

Why are we doing this? asks Rebecca, a little suspicious.

For pleasure, I say. To fill our lives with beauty and adventure. And because its funny.

Each kid has a copy of Don Quixote de la Mancha by Miguel de Cervantes, about one thousand pages bound by a red cover illustrated with a knights helmet blossoming with elaborate, endless swirlsa garden of imaginings gone wild.

Go ahead and write your name in your copy. The book belongs to you.

They write their names in the book.

Whats it about? asks Rebecca.

Percy has already read the first ten pages, right here in class. Its about an old man in Spain who reads all the time, he says, all day and all night, and he starts to believe that the adventure stories he reads are real. Then he loses his mind and believes that he is a knight from those stories, and he decides to go on the road to start rescuing people.

Thank you, Percy. Thats a good summary. Its also a story of two opposites who become friends. The man who reads is Don Quixote, and his neighbor who goes on adventures with himand who cant readis a farmer named Sancho Panza.

That name makes the kids laugh because panza means belly in Spanish.

One girl is not laughing. Her name is Talia, and she is six. Her face is rearranging itself for tears.

Whats wrong, Talia? I ask. Shes sitting directly across the table from me.

I cant read, she answers, her voice squeezed by the struggle not to cry.

Thats okay, I say.

No, its not okay, she answers.

Maybe you could have the job of reading an English translation, so you can help us in case we get stuck.

I cant read at all.

Tears push their way out of her eyes and her hands cant push them back inside.

Lily and Alex, two teenage girls, stand up, walk around the table to Talia and put their arms around her. Everyone waits while she sobs.

At long last, the sobbing subsides and Talia breathes normally. Rebecca brings her a cup of water.

Were all going to read this together, I tell the class. Ill read the story out loud while you follow along. Anyone can help me pronounce the Spanish properly at any time, and readers of Spanish can take over from me whenever theyre ready.

Joshua, our lone teenage boy, is sitting next to Talia. Talia, he says, gently, I can point at the words while the person is reading so you can see what they look like while you hear what they sound like.

Thats very kind, Joshua, I say, and smart. Reading is like recognizing peoples faces and names. Ill show you.

Shielding a piece of paper from view with my arms, I write eight random letters on one side. Then I say to the kids, Im going to show you this paper, with eight letters on it, for two seconds. Then Im going to test you to see how many letters you remember.

No, please dont test us! says Felicity. Its too stressful!

Its not a test like at school. Its a scientific experiment.

After I show them the paper for two seconds, the kids start shouting out letters. The most anyone can remember is four.

Now, I say, Im going to write down eleven letters, show them to you for only one second, and I bet you right now that you will remember every letter.

The kids make sounds that indicate their amazement and doubt.

I write the letters, again shielding them from view, then raise the paper and display it for one second before putting it out of sight.

New York City! they shout in unison with big smiles, including Talia.

They are easily able to name every one of those eleven letters.

Why? I ask. How can you remember all eleven letters when before you could remember only four out of eight?

Because theyre words, says Talia.

Yes! I say. Bravo, Talia! There is structure! The letters are organized into words! The more words you see, the more words you recognize, and the easier it is to read. Its just like recognizing the people in this room and knowing their names. Joshua is going to help you with that.

Thank you, Joshua, says Talia. She takes one deep breath, in and out, and her face relaxes.

Dylan, one of the soccer players in the group, places a yellow card in front of me.

A penalty? For me? What did I do?

Its for making Talia cry.

No he didnt, says Talia. Its just I get in trouble at school when I cant read.

You can read, I say. Youre learning how. Youre always learning.

Wait, says Felicity, rerouting the conversation. What does an old man have to do with us?

A lot. Youll see.

Not everyone speaks that first day of Don Quixote class. Nor do they need to speaknot until theyre ready.

Wendy, aged eight, has the smile of someone who agrees with life. I have never seen her angry or worried or bothered by anything. Her teenaged sister, Ruth, sits next to her, paralyzed by anxiety, her default state. Neither sister says anything.

One girl, Sarah, who at age six in the spring joined the little schoolla escuelita, as the families call itis now seven. As always she is silent; her eyes track everything that happens in the room and her face reveals nothing of what she thinks. She is also drawing with her pencil inside her copy of Don Quixote. I almost ask her not to, but I stop myself. The book belongs to her.

All right, I say, Lets read!

* * *

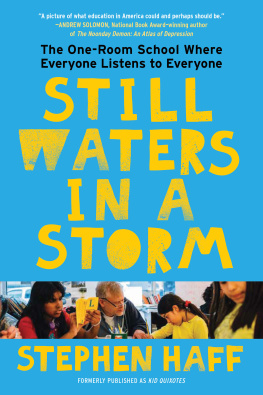

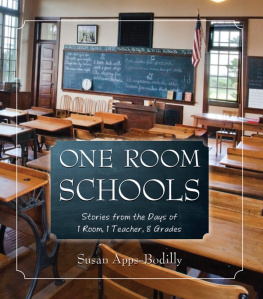

Kid Quixotes weaves together three main narratives: the story of Sarah, a shy little Mexican girl, and her family living in Bushwick, Brooklyn; the story of Stephen (me), a former public school teacher recovering from bipolar depression; and the story of Still Waters in a Storm, the one-room schoolhouse where Sarah and her peers and I translate Don Quixote, adapt it as a bilingual touring musical show, andin the processrescue each other. Running through this weave is the secret world of Sarahs imagination, drawn by her in the margins of the novel, in which she is a superhero battling monsters and defending the defenseless.