Epilogue

Lascaux Revisited

T HE LASCAUX CAVE REMAINS closed to the public, but in the years since Mario Ruspoli created his cinematographic record of the drawings there, the French Ministry of Culture and Communication has built a replica of Lascaux for visitors, and the walls of the cave have been photographed in brilliant color. Archaeologists have examined the drawings with more precise instruments and lenses and now count 1,963 different representations: 915 can be discerned as animals, 434 are signs, and 613 can't be named. There is the one man. They now believe that the horses, with their heavy coats, mark the end of winter and beginning of spring, that the aurochs mark high summer, and that the stagsantlered, depicted in herdsare painted as they were in autumn, just before mating season.

Although the Culture Ministry upgraded the air-conditioning system, in 2001 a technician found mold in the air locks of the entrance site, and within a few weeks the cave floors and ledges were covered in white. Workers suppressed the outbreak with quicklime, but over the next two years, mold continued to grow throughout the cave. In 2003 the ministry began a more comprehensive eradication program, which suppressed the mold once again. Although technicians constantly survey and maintain the site, behind the sealed door of the entrance, the marks of the Paleolithic painters are becoming less and less discernible, and the pigments on the hides of the animals, drawn from memory more than eighteen thousand years ago, are fading.

Meanwhile, our lights draw their own patterns in the dark, as they shine and reflect upward through smoke and ash and cross the same turbulent night winds that make the stars appear to twinkle. If you gaze at the map of earth at night as seen from space, you might imagine the way we appear to astronauts orbiting in the intergalactic silence: come close of day, the earth appears as solids built of illumination and voids created by its absence; in patterns drawn by global drifts of excess and scarcity, thought and afterthought, fortune, innovation, insistence, and accidentpatterns that have been accreting for twenty thousand years and conjure no simple feeling. Look once, and you might be amazed at the gift of so much light. Look again, and you might feel sobered by the enormous extent and reach of it. Look yet again, and the countless lights seem to take on unwitting shapes: see the way the crowded headlands of the eastern seaboard make the shape of a head with an outstretched neck, the peninsula of Florida the forelegs, and the Pacific Coast the agile back legs of a fleet stag gathering speed as it rushes headlong into the black Atlantic.

Acknowledgments

Bibliographic Note

Notes

Index

Acknowledgments

I'm especially grateful to the MacDowell Colony for providing me with the best of places to work, and to the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation for a fellowship that granted me time to complete this book. The Bowdoin College Library; the Curtis Memorial Library in Brunswick, Maine; and the Maine Interlibrary Loan Service were of immeasurable help to me during my years of research. Gratitude also to the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park, New York; to the New Bedford Whaling Museum Research Library; and to David Low at Consolidated Edison.

I've had the support of many friends during the writing of this book, in particular: Elizabeth Brown, who first put the idea for it in my head; E. F. Weisslitz, who had no end of enthusiasm for it; Andrea Sulzer, always curious; and John Bisbee, who lent me his finely tuned ear for the entire time. Many thanks to Cynthia Cannell for her enduring support on behalf of my work; to Barbara Jatkola for her careful work copyediting the manuscript; and, as always, to Deanne Urmy for her intuition, her precision, her faith.

Bibliographic Note

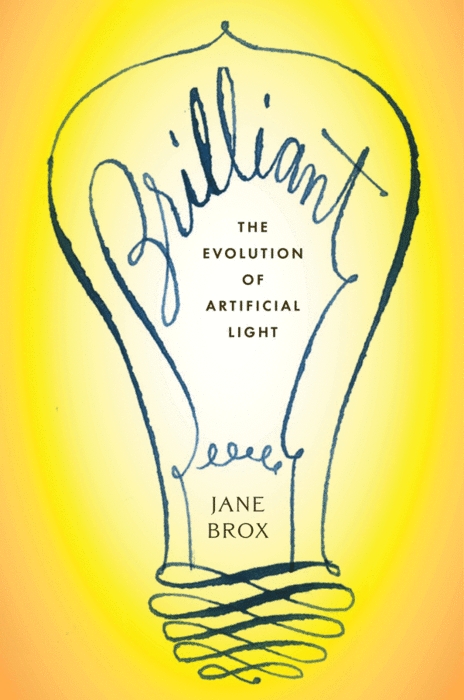

I am especially indebted to the following books for insight and inspiration: Gaston Bachelard, The Flame of a Candle, translated by Joni Caldwell (Dallas: Dallas Institute Publications, 1988); William T. O'Dea, The Social History of Lighting (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1958); Wolfgang Schivelbush, Disenchanted Night: The Industrialization of Light in the Nineteenth Century, translated by Angela Davies (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995); and Mario Ruspoli, The Cave of Lascaux: The Final Photographs (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987).

The first section of Brilliant owes much to A. Roger Ekirch, At Day's Close: Night in Times Past (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005); Yi-Fu Tuan, "The City: Its Distance from Nature," Geographical Review 68, no. 1 (January 1978); Louis-Sbastien Mercier, Panorama of Paris, edited by Jeremy D. Popkin (University Park: Pennsylvania University Press, 1999); Richard Ellis, Men and Whales (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1991); and D. Alan Stevenson, The World's Lighthouses Before 1820 (London: Oxford University Press, 1959). Chapter 2 owes a particular debt to Wolfgang Schivelbush for insight concerning lanterns and the French Revolution, and to Yi-Fu Tuan for thoughts on cities and their separation from the natural world.

For the chapters on electricity, I'm grateful to Brian Bowers, Lengthening the Day: A History of Lighting Technology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998); Philip Dray, Stealing God's Thunder: Benjamin Franklin's Lightning Rod and the Invention of America (New York: Random House, 2005); Jill Jonnes, Empires of Light: Edison, Tesla, Westinghouse, and the Race to Electrify the World (New York: Random House, 2004); Robert Friedel and Paul Israel, Edison's Electric Light: Biography of an Invention (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1987); and Pierre Berton, Niagara: A History of the Falls (New York: Kodansha International, 1997).

For the chapters on early-twentieth-century light, I relied largely on Morris Llewellyn Cooke, ed., Giant Power: Large Scale Electrical Development as a Social Factor (Philadelphia: Academy of Political and Social Science, 1925); David E. Nye, Electrifying America: Social Meanings of a New Technology, 18801940 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992); Katherine Jellison, Entitled to Power: Farm Women and Technology, 19131963 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993); Robert A. Caro, The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Path to Power (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1982); Mary Ellen Romeo, Darkness to Daylight: An Oral History of Rural Electrification in Pennsylvania and New Jersey (Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Rural Electric Association, 1986); James Agee and Walker Evans, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men: Three Tenant Families (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1988); Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English, For Her Own Good: 150 Years of the Experts' Advice to Women (Garden City, NY: Anchor Press, 1978); and Michael J. McDonald and John Muldowny, TVA and the Dispossessed: The Resettlement of Population in the Norris Dam Area (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1982). Chapter 15, especially the section on the sounds of war, owes much to Angus Calder, The People's War: Britain, 193945 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1969).

And for the final section of the book, I'm indebted to A. M. Rosenthal, ed., The Night the Lights Went Out (New York: New American Library, 1965); Catherine Rich and Travis Longcore, eds., Ecological Consequences of Artificial Night Lighting (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2006); and the International Dark-Sky Association website, http://www.darksky.org.