Introduction

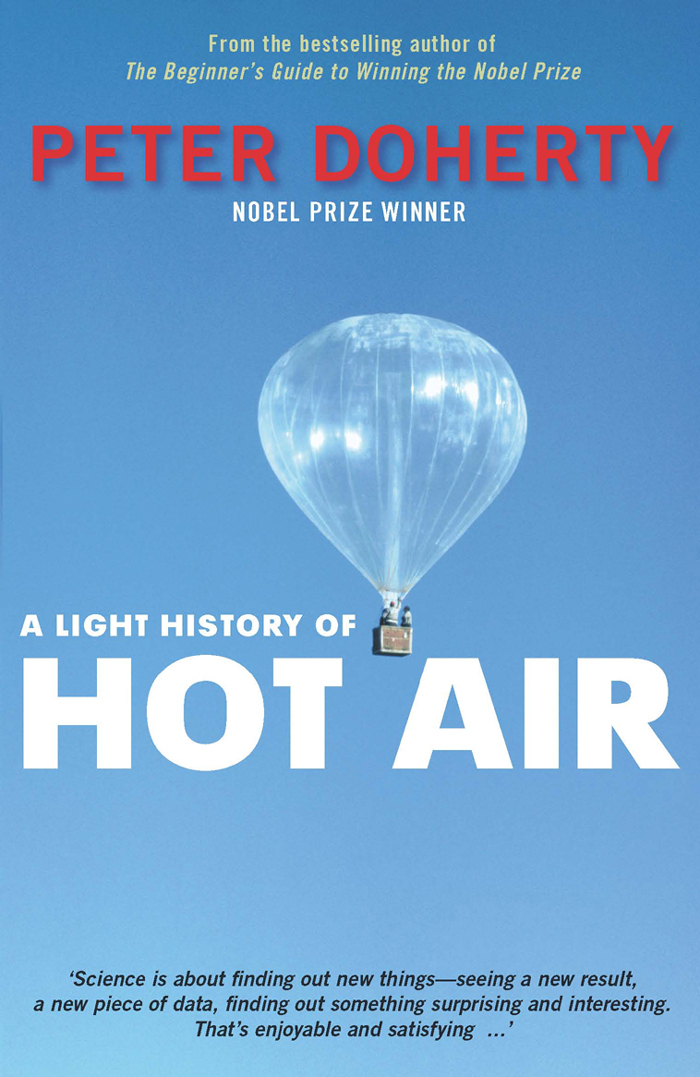

Hot air is such a vast topic that a single book by one person could not possibly be authoritative. My light account is meant to intrigue, entertain and even provoke a little, rather than to be exhaustive or comprehensive. Some of the stories and insights are based on the ordinary, everyday experiences of my wife Penny and me as we lived, worked and raised children on three continents: Australia (Brisbane, Canberra and Melbourne); Scotland (Edinburgh); and the USA (Philadelphia and Memphis). Grandparents and parents appear, partly because much of what is discussed here happened in their lifetimes.

By definition the perspective of a history such as this derives more from the past than from the present; understanding the evolution of events, technologies and perceptions benefits from the distance of time. We in the twenty-first century are experiencing such momentous changes that, with the exception of the greenhouse gas story that is developing so rapidly and cant be ignored in a book on hot air, Ive skimmed over many current happenings. There isnt much here about motorcars, though they are a major source of carbon monoxide and pollution. We all know about automobiles; there are many books about them and there isnt a lot thats interesting to say. On the other hand, the theme of climate change is a fairly constant subtext.

Also central to this story of hot air are the themes of burning and illumination. Both in the actual and the metaphorical sense, burning and illumination are irrevocably linked through the long march of humanity. Over the ages, weve lit big fires and gentle flames to open our minds, to warn of danger, to brighten our way through the darkness and to allow us to read in bed at night. As every photographer and cinematographer knows, the way a scene is lit determines how the subject is perceived.

Big topics such as global warming, environmental degradation, the cause of wars and the nature of political upheavals are juxtaposed here with modest, domestic themes: cooking, air-conditioning, sunburn, going to school on a steam train. Shining an indirect, tangential light has the potential to illuminate issues in new and unexpected ways against the backdrop of history.

Floating in Air

On zoos and the Serengeti

An easy stroll across Royal Park takes us from our narrow, two-storey Victorian house to the entrance of Melbourne Zoo, a fine institution that has its beginnings in the sixth and seventh decades of the nineteenth century. Around the mid-point of that walk stands a stark pile of stones marking the assembly point of the ill-fated Burke and Wills expedition which, with great expectations, set out in August 1860 to cross the Australian continent from south to north.

Apart from the nineteen humans from different regions of the globe, the most exotic creatures in the Burke and Wills menagerie were twenty-seven camels imported especially from India. After slogging across increasingly harsh landscapes, the explorers reached the distant, inland oasis of Coopers Creek, where they made their sixty-fifth camp. Then, in the full heat of a Central Australian December, Robert OHara Burke and William John Wills led a party of four in a dash north to the Gulf of Carpentaria. Only one member of that small group, James King, survived. By the nature of their deaths and the idiosyncrasies of Burkes character, they became, like Gallipoli and Ned Kelly, enduring icons in the Australian legend. Several of the paintings in Sidney Nolans Burke and Wills series isolate the two men and their camels in the stark, bare redness of the desert landscape. Others illustrate their solitary deaths on the banks of Coopers Creek. The more effective and better organised John McDougall Stuart, who completed the south-to-north trip in 1862 and set the route for the later overland telegraph line, is much less well remembered.

Coastal Melbourne at the southern tip of the continent is a considerably gentler environment than inland Australia. On occasional summer weekends, when our bedroom windows are open and the clock radio isnt set to rouse us with classical music, the first thing we hear is the sound of the zoo monkeys chattering on the other side of Royal Park. Sometimes when the wind is blowing steadily from Bass Strait in the other direction, we wake suddenly to what sounds like a lion roaring right over our heads. Only it isnt a lion, but the gas burners of a hot air balloon floating across the city from the Melbourne Cricket Ground, rapidly losing altitude as it comes in to land.

At times, the balloons just miss the highest point of the roof above us, the now ornamental chimney pots. The pilot activates the burners, the flames leap high into the canopy, and the balloon lifts a little so that it can also clear the row of tall houses opposite. We are relieved as we recollect what it cost recently to replace the 1873 Welsh slates with a more recent Spanish variety. On one of the balloonist entrepreneurs busier mornings, as many as six or eight of these exotic, brightly coloured visions, with their advertising logos, skilled drivers and paying passengers in suspended baskets, float across at different heights, then drop rapidly out of sight as they settle onto the flat grassland of Royal Park. These early morning venturers are then whisked off to a champagne breakfast in a city hotel, while the balloon crew deflates the canopy and packs everything onto the back of a truck. Watching this wind-up phase as we stride around the walking circuit in the park takes us back to our own experience of ballooning in Africa.

Also less hostile than the Australian interior crossed by Burke and Wills is Kenyas Mara landscape. The vegetation is different and the animal inhabitants are more varied, and in some cases considerably more dangerous, than emus and kangaroos. Setting out from somewhere near the luxurious, tented Governors Camp, our floating chariot drifted above the annual wildebeest migration in the Serengeti region of Kenya and Tanzania. Before we landeda process that involved the wicker basket dragging across the ground on its side till the canopy above us fell to earthwe were told to brace and not jump out prematurely. Some of the big cats might be hungry and ready to pounce on a slow-moving, poorly protected, inferior creature that suddenly dropped in at breakfast time.

The balloon ride was pure magicquite different from the other African safari adventure of bouncing across the ground in a four-wheel-drive troop carrier as the guide tries to manoeuvre close to a group of elephants or, if youre very lucky, a leopard or a rhino. The animals seemed to ignore the canopy floating above them and were completely unfazed by the sporadic roar of the gas burners. We looked down on thousands of wildebeest, crocodiles sunning themselves on muddy banks, hyenas, wart hogs, giraffes and different types of gazelles. A small herd of zebra grazed contentedly while a pack of lions ate one of their species just off to their left: why worry if the lions are well fed? Much of what wild animals do with their time is concerned with maintaining their calorie intake. What I remember most is a great sense of peace and the extraordinary variety and vibrancy of the spectacle that stretched beneath us. On our way to a picnic breakfast of bacon and eggs cooked over the multi-use balloon burners, we enjoyed a vision that no human born more than 230 years ago could have known.