MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

Level 1, 715 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

mup-contact@unimelb.edu.au

www.mup.com.au

First published 2018

Text Peter Doherty, 2018

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2018

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

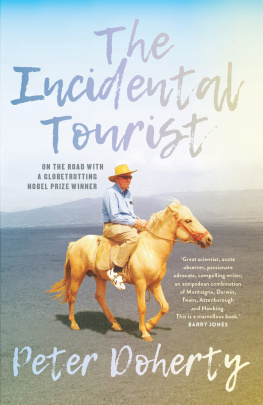

Cover design by Peter Long

Cover image courtesy of Peter Doherty

Typeset by Sonya Murphy, Typeskill

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

ISBN 9780522871722 (paperback)

ISBN 9780522871739 (ebook)

Contents

Experiments, data and connections

ANYONE LIKE ME, BORN during the Second World War in Australia, has lived through a time of massive change. Compared with our parents and grandparents we enjoy longer, healthier and more pain-free lives. Food is readily available, with fresh produce being easily imported from distant countries rather than being seasonally dependent. We communicate online with friends and colleagues thousands of kilometres from us, seeing their faces in real time on the screen as we do. Flying across the oceans for work or vacations is now routine and unremarkable. All this, though, has only happened within the last fifty years.

These transformations are a direct consequence of scientific discoveries and technological advances that have revolutionised the ways we connect and communicate. Scientists who have always lived with the consciousness of probing universal truths were, for obvious reasons, early adopters of both international air travel and web-based communication. Ive been a frequent flyer throughout most of the jet age.

My wife Penny and I (the we in this book) have lived in Edinburgh (196771), Canberra (197275 and 198288), Philadelphia (197581), Memphis (19882017) and Melbourne (1998present). The overlap in dates reflects that, after I was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1996 and Australian of the Year in 1997, we commuted between the United States and Australia. Until mid 2002, I spent 75 per cent of my year working at St Jude Childrens Research Hospital in Memphis. That profile then reversed when I took up an appointment at the University of Melbourne Medical School and we made our primary home in the adjacent area of South Parkville.

Living in different societies has been a great experience, but the primary reason we moved around was career choices. Biomedical researchers interrogate nature by doing experiments, collecting data and connecting the dots. Such science is expensive and Australia, with a relatively small population, can only excel in a limited number of areas. The best opportunities are often elsewhere.

Although this book uses the substrate of travel related to my job as a scientist, it isnt a science book. The experiments discussed here have resulted from spending just a little time in different places, some familiar, some obscure. The data is what we saw and experienced and at least some of the connections have come from another personal obsession: a fascination with history and how/why things happened. Of course, such storytelling rates neither as science nor history or travel. Its, sort of, memoir.

Each of the chapters is a separate entity, and they have been organised in no particular sequence of time or place. Much of what Ive written is from memory, and memory is notoriously flawed. Hopefully, though, in seeking to extract hints of meaning, some small insights have emerged that are of interest.

The popularity of TV programs like Who Do You Think You Are? and websites like Ancestry.com make it obvious that theres an underlying need to place our lives in some bigger, yet personal, historical context. As Ive written about different cities and cultures across the planet, its been particularly intriguing to develop unexpected linkages to the Australian experience. Whats the connection between CATS and Captain Cook? (Hint: Its not to do with either felines or Andrew Lloyd Webber!) Were you aware that the American Civil War helped to populate Queensland? Whats the deeper story behind those big guns we see frequently in the main streets of Australian country towns? Some of these discoveries surprised me when I stumbled on the information. Perhaps my journey of discovery will intrigue you, too!

CHAPTER 1

The incidental tourist

INCIDENTAL TOURISM (AS DISTINCT from travelling while being on a vacation) is primarily a consequence of the truncated time-frames enabled by rapid international jet travel. As we all know, the realities of our world are vastly different from anything that has gone before. It once was a very big deal for a leading Australian researcher (like 1960 Nobelist Sir Macfarlane Burnet, the virologist/immunologist) to attend an international conference. Back then, junior Australian medicos would have to defray the cost of taking up (for further certification) a hospital job back home (Britain) by signing on for an extended trip as a ships doctor. As late as the 1950s, all but the wealthiest (and most adventurous) Antipodean business leaders, marketers, commercial buyers and the like spent weeks at sea as they headed to the major centres of wealth and power in the Northern Hemisphere.

Crime and romance novels set on ocean liners in those more leisured years depended in part on the reality that such languid voyages led even the most dedicated professional to morph into a less critically minded, more relaxed mode. Fuelled by alcohol and boredom, with diverse company and hours to kill, there was time for contemplation, talking with strangers from different cultures and reading about ultimate destinations. Being on the deep blue seas for days provided ample scope for literary seduction and murder.

The first hint of change for the Australian, well-to-do, long-distance traveller was in 1935, when Qantas Empire Airways (as it was called from 193467) partnered with Imperial Airways (the precursor of British Airways) to launch a pioneering service to Britain. With thirty-one stops over twelve days, the initial legs from Australia to Singapore were on a DH86, the two-engined De Havilland Dragon biplane that would see extensive use with Australias Royal Flying Doctor Service. On board this first version of the Kangaroo route was Lady Edwina Mountbatten, wife of the last Viceroy of India. No doubt, an early example of celebrity advertising.

Then, not long after the Second World War, eminent physicist (later Sir) Mark Oliphant, a significant player in the Manhattan Project (at the University of Birmingham and University of California, Berkeley) that produced the first atomic bombs, was recruited from the United Kingdom to direct one of the research schools at the new Australian National University. As he related in an interview with ABC science communicator Robyn Williams, Adelaide-born Oliphant and his wife Rosa returned to Australia on a converted Second World War Lancaster bomber (carrying one flight attendant and six passengers and with flat beds), a trip that took only sixty hours. Flying at about 2500 metres, the view of the landscapes that passed below was evidently unforgettable. Sir Mark also recalled that he could rest his back on one side of the fuselage and brace his legs on the other. Now thats a narrow body! Peer up-close into the Lanc preserved at the Imperial War Museum, London, or inspect G-for George at the Australian War Memorial, and it is obvious these planes were designed for war, not peace.

Next page