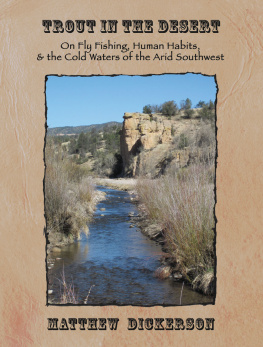

Matthew Dickerson begins Trout in the Desert with a childhood memory of a nameless, pristine trout stream, small enough to straddle, in the Sangre de Cristo mountains of New Mexico. Thirty years later, he leads us on a tour of of the Desert Southwest, fishing the San Juan River, the Colorado River (at the head of the Grand Canyon), the Gila River, and finally the Frio and Guadalupe Rivers in the Hill Country of Texas.

But more than just stories of discovering cold-water trout in unlikely (and often blisteringly hot) places, Dickerson examines the history of trout in these waters and the health of their delicate ecosystems.

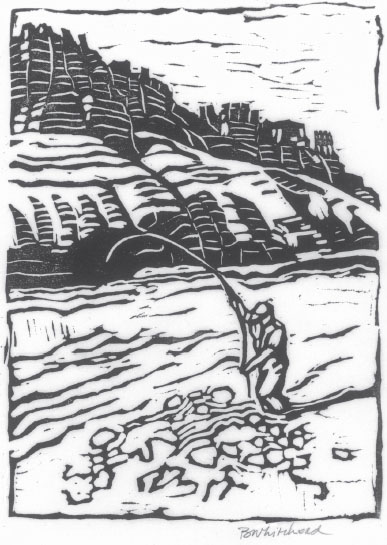

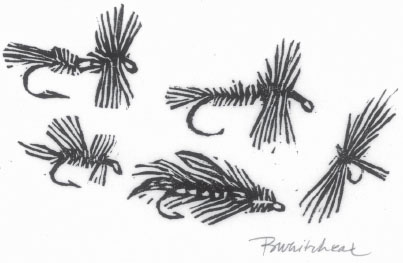

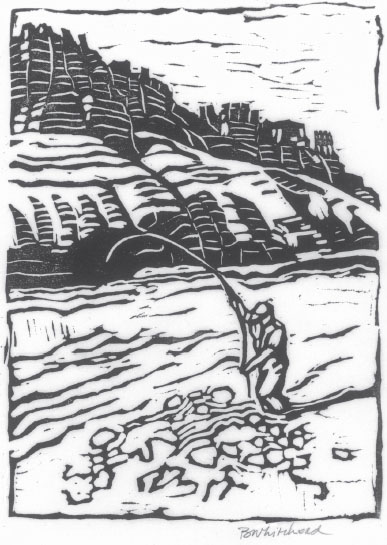

This lovingly described journey is neither an historical nor a scientific text, but the writing is informed by both. Fascinating details of both stream ecology and the history of human habitation and consumption abound. The book is illustrated by original prints from Texas artist Barbara Whitehead.

Trout in the Desert: On Fly Fishing, Human Habits, and the Cold Waters of the Arid Southwest 2015 by Matthew Dickerson

First Edition

Print Edition ISBN: 978-1-60940-485-7

ePub ISBN: 978-1-60940-486-4

Kindle ISBN: 978-1-60940-487-1

PDF ISBN: 978-1-60940-488-8

Wings Press

627 E. Guenther San Antonio, Texas 78210

Phone/fax: (210) 271-7805

On-line catalogue and ordering:

www.wingspress.com

All Wings Press titles are distributed to the trade by Independent Publishers Group www.ipgbook.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Dickerson, Matthew T., 1963

Trout in the desert : on fly fishing, human habits, and the cold waters of the arid Southwest / Matthew Dickerson ; Illustrations by Barbara Whitehead. -- First edition.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-60940-485-7 (cloth / hardcover : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-1-60940-486-4 (epub ebook) -- ISBN 978-1-60940-487-1 (kindle/mobipocket ebook) -- ISBN (invalid) 978-1-60940-488-8 (library pdf)

1. Trout fishing--Southwest, New--Anecdotes. 2. Environmental degradation--Southwest, New. 3. Nature--Effect of human beings on--Southwest, New. I. Title.

SH688.U6D53 2015

639.27570979--dc23

2015022510

Contents

The difference between a path and a road is not only the obvious one. A path is little more than a habit that comes with knowledge of a place. It is a sort of ritual familiarity. As a form, it is a form of contact with a known landscape. It is not destructive. It is the perfect adaptation, through experience and familiarity, of movement to place; it obeys the natural contours; such obstacles as it meets it goes around. A road, on the other hand, even the most primitive road, embodies a resistance against the landscape. Its reason is not simply the necessity for movement, but haste. Its wish is to avoid contact with the landscape; it seeks so far as possible to go over the country, rather than through it; its aspiration, as we see clearly in the example of our modern freeways, is to be a bridge; its tendency is to translate place into space in order to traverse it with the least effort. It is destructive, seeking to remove or destroy all obstacles in its way.

Wendell Berry, A Native Hill

Prologue:

Just A Lot of Hot Air

T he year I began writing this book, 2013, was also the year I turned fifty, celebrated my twenty-fifth anniversary, began my twenty-fifth year in my current job (teaching at Middlebury College), and saw my oldest son graduate from college and get engaged. These milestones of aging prompted a certain amount of reflection on my career, my family, my past.

I dont enjoy air travel, I dont like being away from my family, and I cant say I like spending all day listening to lectures at conferences. However one of the few benefits of academic traveland one of the many benefits of being a parent and taking long family vacations, driving and camping our way from Vermont to Yellowstone National Park and backis that by the time I reached my fiftieth birthday I had managed to catch trout on a fly in twenty-five of the United States. New Mexico was the fourth of these, just after Colorado. Texas was the twenty-second, ahead of New Jersey, Oregon and Washington (and, of course, also ahead of all the other twenty-five states in which I had not yet enticed a trout with a fly).

Somewhere between New Mexico and Texas came my first excursion fly-fishing in Arizona. It was early June of 2006. I had a computer science conference in Sedona, and so I flew to Arizona two days early to spend time fishing the Colorado River at Lees Ferry. Lees Ferry (which hasnt actually had a working ferry since 1929 when the Navajo Bridge was constructed to span the Colorado River) is now a campground and boat launch in the starkly beautiful Vermillion Cliffs National Monument. It is at the tail end of Glen Canyon, the head of Marble Canyon and the Grand Canyon National Recreation Area, not too far upriver from the confluence of the Little Colorado and the Colorado Riverwhere the Grand Canyon itself is officially said to begin.

I arrived at the Lees Ferry Lodge at Vermillion Cliffs around midnight after a late drive up from the Phoenix airport. The owner, not wanting to wait up, left the key out in an envelope with my name. I found my room, went to bed, and got up at dawn eager for a day of fishing.

Despite being in the middle of nowhere, the existence of the Lees Ferry Anglers Fly Shop a hundred yards down from the lodge suggested a fishing culture: at least enough destination anglers (like me) coming during tourist season to support a fly shop and a guide service. As I learned, however, Vermillion Cliffs has a low population at that time of June. (At least it did the year I was there.) The campground up the road at Lees Ferry would also prove to be nearly empty. The handful of tourists I met at the lodge restaurant over the course of four meals were not in the area to fish, but to watch California condors. Though apparently there were a couple of guided boat trips up into Glen Canyon during the two days I was there, nobody else had come to Lees Ferry to catch trout. When I went into the fly shop after breakfast to purchase a fishing license and a few local fliesand to get whatever hot local fishing tips they were willing to dispense along with the fliesthe only person in the shop was the guide who worked there.

The guides fly suggestion was #22 zebra midges in different colors, which I dutifully purchased to supplement the few I had left over from trips to New Mexicos San Juan River. His other advice was to stay in the section of river upstream of the public beach and the confluence of the nearly dry creek bed that bore witness to the muddy Paria River. Downstream of the Paria, bait fishing is allowed. Upstream from the confluence, the Colorado is regulated for catch-and-release fishing using barbless hooks. The beach gets heavily fished by local worm anglers keeping whatever they catch, he told me. They dont leave many trout.

I was not there to keep fish, and I was used to crimping my barbs, so his advice sounded good.

On that first of my two mornings at Lees Ferry, since I had to check into the lodge and visit the fly shop, it was well after dawn before I was en route to the river. The eight-mile drive along Vermillion Cliffs to the river access was beautiful, though not as stunning as it would be that evening at sunset, or the next morning when I would make the drive at sunrise. It was also very foreign to the landscapes where I had spent most of my life. Vermillion Cliffs National Monument is aptly-named. Deep red canyon walls are punctuated here and there by towering rock pinnacles knifing the faded blue skies. Where the cliffs are not vermillion, they are horizontally layered and striated in patterns of brown, dark red, ecru, and mauve, broken up by signs of old landslides and glimpses of little slot canyons. Closer to the river, erosion has rounded the lower rock outcroppings, giving them the appearance of broken halves of giant beehives or wasp nests.

Next page