Contents

Guide

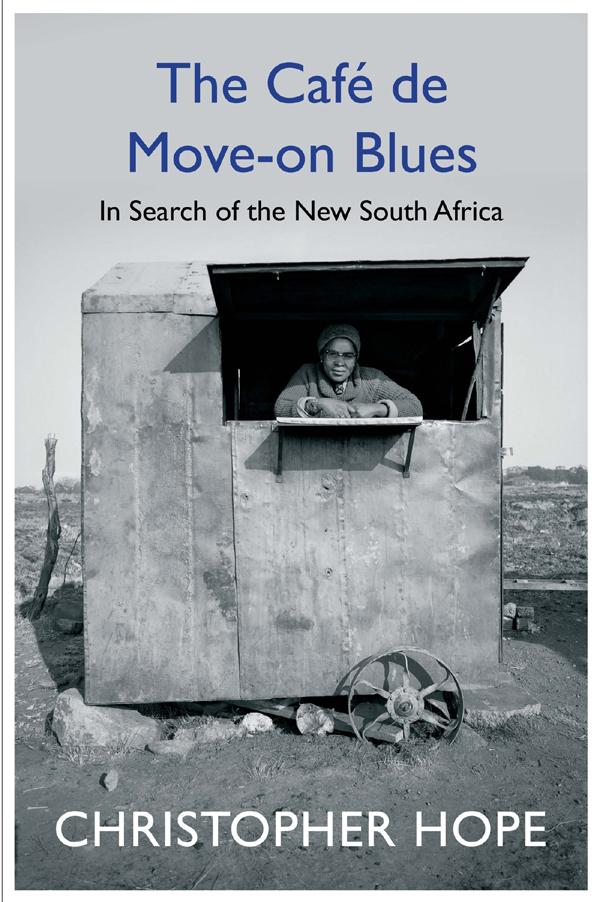

The Caf de Move-on Blues

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

NOVELS

A Separate Development

Krugers Alp

The Hottentot Room

My Chocolate Redeemer

Serenity House

Me, the Moon and Elvis Presley

Darkest England

Heaven Forbid

My Mothers Lovers

Shooting Angels

Jimfish

SHORT STORIES

The Love Songs of Nathan J. Swirsky

Learning to Fly

The Garden of Bad Dreams

NON-FICTION

White Boy Running

Moscow, Moscow

Signs of the Heart

Brothers under the Skin: Travels in Tyranny

POETRY

Cape Drives

Englishmen

In the Country of the Black Pig

FOR CHILDREN

The King, the Cat and the Fiddle (with Yehudi Menuhin)

The Dragon Wore Pink

The Caf de Move-on Blues

In Search of the New South Africa

CHRISTOPHER HOPE

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2018 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Christopher Hope, 2018

The moral right of Christopher Hope to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

The illustration credits on p. constitute an extension of this copyright page.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-78649-059-9

Trade paperback ISBN: 978-1-78649-523-5

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78649-060-5

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-78649-061-2

Map artwork by Jeff Edwards

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Georgie, wherever he may be

Contents

Preface

T his is an account of a journey around South Africa. It is a search for understanding of who we are and what we thought we were doing there. People like myself, and those from whom I came: English-speakers, descendants of European settlers, or Whites to use the weary, inevitable classification, and thus South Africans, of a certain sort. It was a search unlikely to succeed because the country is one where the more you know, the less you understand, but that in no way lessens the need to go on looking. It began in April 2015, when a statue of Cecil John Rhodes, the imperial fortune hunter, was attacked on the campus of Cape Town University. I happened to be there at what proved to be the start of the statue wars.

With each passing week, effigies across South Africa were assaulted, strung with placards, toppled, and daubed with paint and other ordures. The variety of statues targeted was surprising. Besides British imperialists and Dutch colonialists, they included Black revolutionaries, an Indian pacifist, KhoiSan icons, several stone elephants, three monarchs, one tiny rabbit and a horse. Not only statues but paintings, photographs, books and libraries were torched, lecture halls trashed, teachers threatened and assaulted. Race came into it, of course in South Africa it always does. Many, but not all, of the iconoclasts were Black and most, but by no means all, of the statues assaulted depicted Whites.

It was about this time that I came across an account, given in James Fentons wonderful little book On Statues, of an attack that took place on the sacred images and icons of churches in Bruges, during the French Revolution. Fenton quotes an observer:

The Heads of the statues taken from the Town Hall were brought to the marketplace and smashed to pieces by people who were very angry and embittered. They also burned all traces of the hateful devices that had previously served the Old Law, such as gibbets, gallows and whips. Throughout these events the whole market square echoed to the constant cries of the assembled people: Long live the nation! Long live freedom!

(John W. Steyaert, Late Gothic Sculpture: The Burgundian Netherlands, Ghent, 1994)

Using these mute assaulted statues as navigation pointers on my map, or windows through which to see the forces at work, I travelled the country. South Africa does not allow much realism, it makes itself up as it goes along, is a work in progress, and it demands you read through to the real drama beneath the surface. It is often surreal, sometimes unhinged and always unexpected. The journey took me to most of the provinces in South Africa, and sometimes to places where, though to anyone else there was not much to see, I had lived and worked and where bits of my life lay buried or hiding, waiting to be rediscovered and where memories welled up in me. These were intensely personal memorials, invisible to others but as solid to me as anything in bronze or marble.

A number of people who spoke to me asked me not to use their names; a few asked me not to take notes; and, in one case, I was asked not to remember what I had been told because I was an inappropriate repository. Yet people wished to talk and once started they did not stop. Not since I spent time in the former Soviet Union have I found people switching between two ways of talking: private truth and public pretence; kitchen-table confidences and official fictions. Censorship, once so familiar to many of us under the old regime, was making a comeback. But this time we were doing it ourselves. Ideas, phrases and sentiments were on the banned list once again and words were weaponized. That is why I have altered the names of everyone who spoke to me and, sometimes, their genders.

Above all, I wanted to look again at the people who made me who I am: Whites who settled in South Africa and believed that they were at home there. If ever freedom was won in South Africa, so went the dream of Oliver Tambo and Nelson Mandela in the dark years of racial hatred, the country would at last belong to all who lived there, with no account paid to colour and creed.

What the fallen statues seemed to say was that this dream was dying. A quarter of a century into the new democracy, I found race and colour to be more divisive than ever. The war of words had never felt more violent. Black people were more and more unforgiving; Whites were angry and baffled, redundant or demonized, their choices narrowing to psychic withdrawal, or the Great Trek in reverse, as they faced up to loss not just of power but of meaning and substance, of being slowly but surely moved on, and out.

The truce that followed the accession of Mandela, when the old adversaries love-bombed each other with rainbows, was over. We had now a proxy war, where each side attacked the others sacred idols because these were next best to the real thing. It was a way of getting at those you wanted removed but were not yet quite prepared to attack outright. In that quintessential South African fashion, we set out to hunt the hostile others, and kept meeting ourselves coming the other way.