Contents

Guide

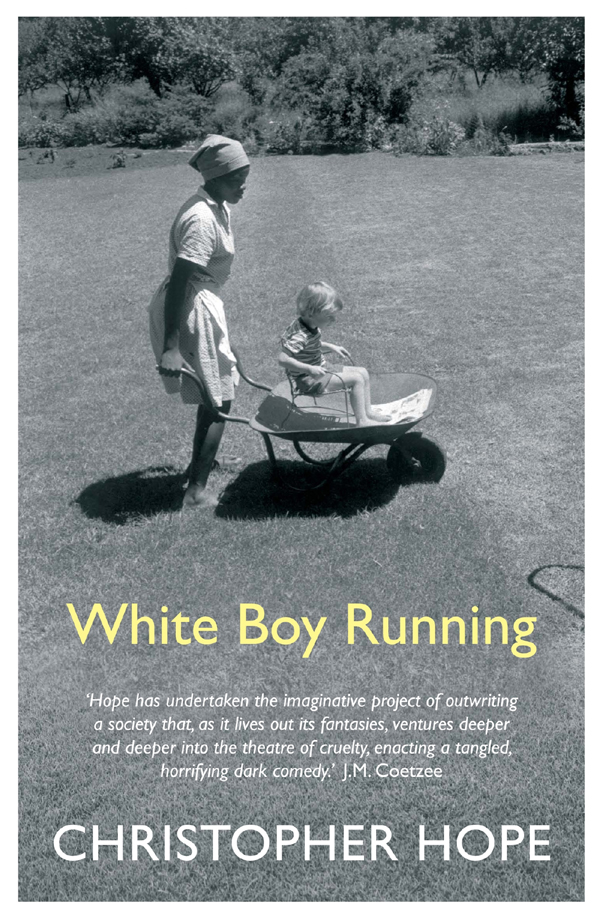

White Boy Running

Christopher Hope was born in Johannesburg in 1944. He is the author of Krugers Alp, which won the Whitbread Prize for Fiction, Serenity House, which was shortlisted for the 1992 Booker Prize, as well as My Mothers Lovers and Shooting Angels, which were both published to great acclaim. He is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

Also by Christopher Hope

FICTION

Jimfish

Shooting Angels

My Mothers Lovers

Heaven Forbid

Darkest England

Me, the Moon and Elvis Presley

Serenity House

My Chocolate Redeemer

Black Swan

The Hottentot Room

Krugers Alp

A Separate Development

SHORT STORIES

The Garden of Bad Dreams

Learning to Fly and Other Tales

The Love Songs of Nathan J. Swirsky

NON-FICTION

Caf de Move-on Blues

Brothers Under the Skin: Travels in Tyranny

Signs of the Heart

Moscow! Moscow!

White Boy Running

POETRY

In the Country of the Black Pig

Englishmen

Cape Drives

Whitewashes

FOR CHILDREN

The Dragon Wore Pink

The King, the Cat and the Fiddle (with Yehudi Menuhin)

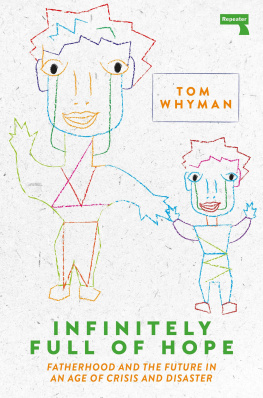

White Boy Running

CHRISTOPHER HOPE

First published in Great Britain in 1988 by Secker & Warburg Ltd.

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2018

by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Christopher Hope, 1988, 2018

The moral right of Christopher Hope to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The three lines from Two Climbs are reprinted by permission of Faber & Faber Ltd from Collected Poems by W. H. Auden

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 642 3

E-book ISBN: 978 1 78649 643 0

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Kathleen Mary McKenna Hope

Fleeing from short-haired mad executives,

The sad and useless faces around my home,

Upon the mountains of my fear I climb.

W. H. Auden Two Climbs

Someday a grubbing historian may read the back files of South African newspapers and marvel that such warnings should have passed unheeded. But the fact is that the Transvaal Government and its sympathisers had become indifferent to warnings followed by no results and accustomed to prophecies unfulfilled.

J. P. FitzPatrick The Transvaal From Within 1899

Authors Note

I N 1987 I travelled in South Africa. I went afresh in search of the country I had left several years earlier, in the hope of finding, and confronting, something of myself. An explosive election had been predicted: there was bombast among politicians and there were bombs in the streets. The apartheid regime, that mix of the brutal and the bovine, stamped on all dissent. But in black townships like Soweto, and elsewhere, revolt was in the air.

In White Boy Running I tried to portray the surreal heart of the country by collecting evidence from the most expert witnesses, those on the ground, on all sides and from all races. Whites still called the shots but their self-possession was faltering. Even those who ran the country seemed to accept that the cruel and fatuous division of citizens, according to the colours of their skins, could not last much longer. It had been seen by those who hated it as a monument to stupidity; but now even its acolytes had begun to regard it as a serious mistake. A dream was abroad; bold spirits in the opposition press even proclaimed that real change was at hand, even if true freedom might be somewhat delayed.

As things turned out, that fateful election was a disaster. The very faintly democratic opposition was trounced by a right-wing coterie who wanted not less but even more apartheid exuberant race-mongers won on every level. As the Zulu leader, Mangosuthu Buthelezi observed on the morning after the debacle: Whites would rather destroy South Africa than institute a policy of real change. So great was the sadness I witnessed among those who hoped for change that some wept when they spoke about it. It was funeral weather and nothing it seemed would change until bloody race conflict, which many felt sure was coming, finally erupted.

Never say never. Just a few years later, Mandela was out of jail, and after free elections, he was sworn in as president to the new South Africa. New was a word on many lips. A mood of blazing optimism, as deep and alarming as the earlier pervasive gloom, took over the country. There was universal rejoicing and rainbows as far as the eye could see. These turned out to be the mirages South Africa conjures up, first to beguile and then to baffle, those rash enough to think they know what is really happening.

I travelled around South Africa once again, very recently, with much the same questions I asked myself thirty years ago on that long road trip that became White Boy Running: Who are we and what are we doing here? This time I found a country once again on the edge of a nervous breakdown, plagued by what I called the move-on blues The old familiar racism was back, ugly and angry. Violence was everywhere. The celebrated rainbow had led not to a pot of gold but to a can of worms. And that of course made the country I found in Caf de Move-on Blues eerily familiar. A realm where appearances are always misleading and where all absolutes about all subjects are always wrong.

Has anything much changed since I wrote White Boy Running? Very little and everything, would be an answer but saying what those terms mean is the challenge. And whenever you sound or seem too certain about anything the country has a way of having the last laugh.

In White Boy Running I recounted a meeting with a Mormon Afrikaner, freshly returned from his first visit to Salt Lake City. He startled me all those decades ago by stating flatly the predicament discussed by few White South Africans at that time: Maybe Africa is for the Africans, he suggested and our mistake was arriving here in the first place He wondered aloud whether if all of us moved to the US might that be best? But then again: didnt America also have its indigenous people? This talent to resist and subvert, to ask the question without an answer, found in unlikely people and unexpected places, made it possible to write White Boy Running, and still consoles and delights me.

Christopher Hope

2018

CONTENTS

PART I

The Stone in the Tree

PART II

Visiting the Elephant Bird

PART III

Good Morning, Lemmings!