Contents

Guide

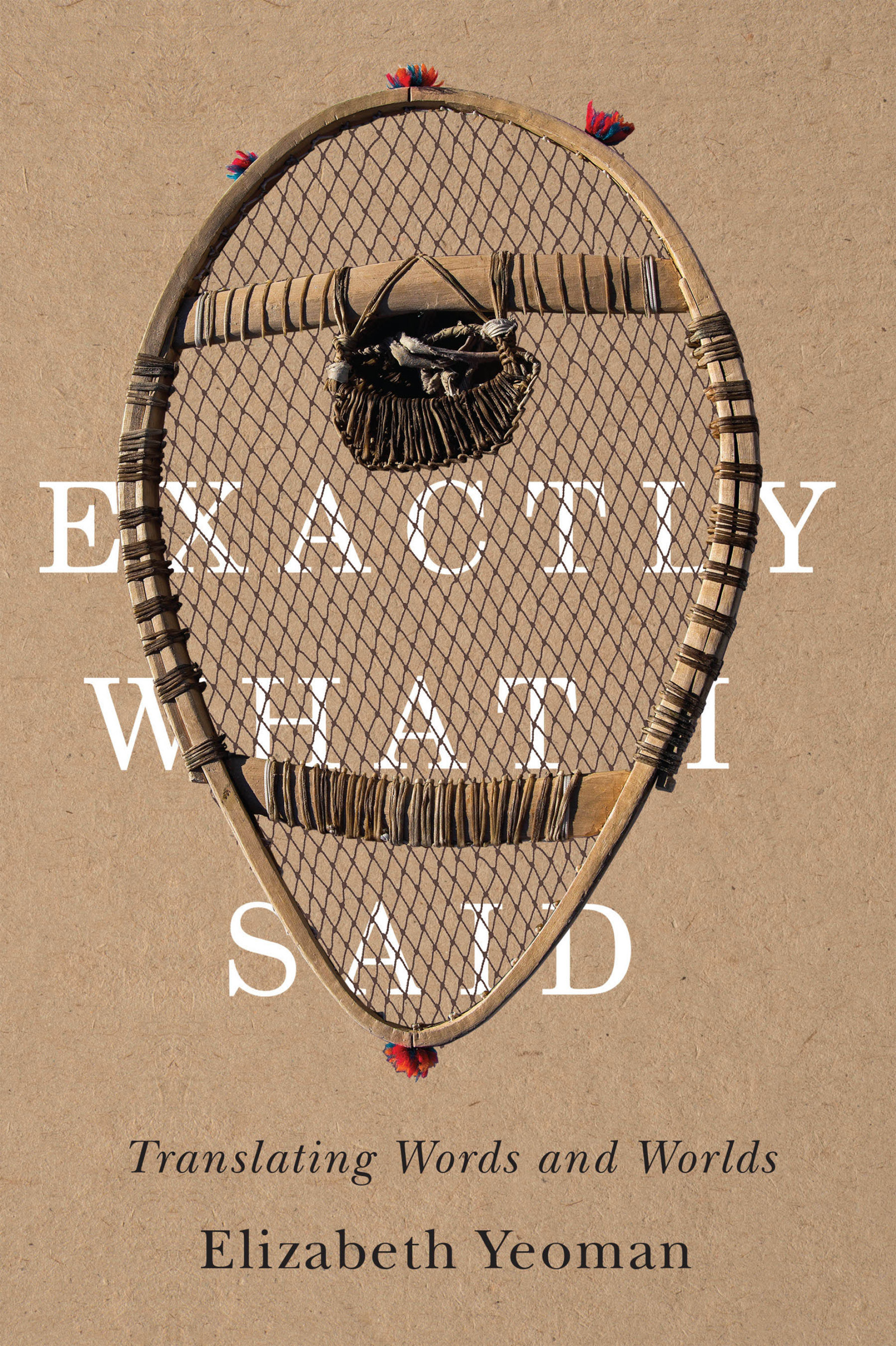

Exactly What I Said: Translating Words and Worlds

Elizabeth Yeoman 2022

26 25 24 23 22 1 2 3 4 5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database and retrieval system in Canada, without the prior written permission of the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or any other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, www.accesscopyright.ca, 1-800-893-5777.

University of Manitoba Press

Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

Treaty 1 Territory

uofmpress.ca

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

ISBN 978-0-88755-273-1 (PAPER)

ISBN 978-0-88755-275-5 (PDF)

ISBN 978-0-88755-276-2 (EPUB)

ISBN 978-0-88755-278-6 (BOUND)

Cover design by David Drummond

Interior design by Jess Koroscil

Cover image by Ryan Wood (Instagram: @ryanwoodphoto)

Printed in Canada

This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

The University of Manitoba Press acknowledges the financial support for its publication program provided by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Manitoba Department of Sport, Culture, and Heritage, the Manitoba Arts Council, and the Manitoba Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Tshaukuesh: Tshi mishta nashkumitin numat, nuitsheuan.

To Tshaukuesh, with heartfelt thanks.

Contents

When the snowshoe design was proposed, I asked Tshaukuesh how she felt about it. I said I wondered whether the use of the snowshoe image might be seen as a cultural appropriation. Her response (used here with her permission) was this: Maybe people will think you used the snowshoe picture because you were proud and happy that you learned from Innu. You walked with us and heard our stories and now you understand a little bit more about us. Some Akaneshau dont know anything about Innu life. Thats why I invite them to walk with me, so they can understand us better. You walked with me so now you know I walk to protect the land, the animals, everything. You respect me and my walk.

I remember my mom and my dad, always walking in the winter with the toboggan. Every time I walk, I walk everything protect. Sometimes evenings we sit down together, talk about why we walk: protect the land, Innu culture, animals... like a circle. I just couldnt wait next year to walk again. Be strong when we walk. So beautiful. Tshaukueshs soft voice and hesitant English resonate in my headphones, her longing and determination palpable despite the geographical and cultural distance between us. She is at the CBC Radio station in Goose Bay and I am in a recording booth in St. Johns. Her voice breaks as she continues: Look, people, look, young children. I can see in their faces, so happy. I wish youd be always like that. Whats going to happen?

It was the first time Tshaukuesh and I had ever spoken to each other, but I knew her work and her reputation. Everyone in Newfoundland and Labrador does, and so do many more all over the world. She had been leading this annual weeks-long walk in InnusiInnu territorysince the 1990s as a way of demonstrating that this is Innu land and the Innu are still here, still using it.

Tshaukuesh set out on her walk, or meshkanau, as a tiny child in the 1940s. Her first steps were taken in Innusi with her family when they were still living a nomadic life following the seasonal rhythms and bounty of the land. Her walk was disrupted by colonization in the 1960s, as she describes in her book, Nitinikiau Innusi: I Keep the Land Alive (2019). In the 1980s she began walking again, in protest, onto the NATO base in Goose Bay and into the vast areas of Innu territory where NATO was training fighter pilots and testing weapons. She had never spoken publicly before that and was not comfortable in English, but gradually she became a spokesperson for the Innuin the courts, at hearings and inquiries, and to the media. Her anger at the invasion of Innusi by the military gave her courage and, as her book documents, she has never faltered in her campaign to protect the land she loves so much.

Looking towards Akami-uapishku (White Mountain Across). Photo by Camille Fouillard.

I met Tshaukuesh in person a couple of years later when she came to St. Johns to accept an honorary doctorate from Memorial University. We talked about the walk and, to my surprise, she invited me to accompany her and her family and friends as they travelled on snowshoes from Sheshatshiu to Enipeshakimau. I said I thought it was only for Innu but she replied that anyone who wanted to come was welcome. In the early spring of 2008 I joined them. People ask me how far we walked, but I have no idea of the distance in miles or kilometres. We took our time, trudging wide-legged on bear-paw snowshoes and hauling all our belongings on toboggans across frozen marshes, through snow-covered boreal forest, and up into the mountains of Akami-Uapishku, sleeping on fir boughs and caribou skins in the big Innu tent at night. We might not have covered a huge distance by the standards of a society dependent on cars and airplanes, but each day revealed a new world, one where life was hard but where there was also extraordinary beauty, warmth, and comfort in the company of Tshaukuesh and her friends and family. I kept a diary during the days I walked with them, and I include it here because I think it conveys something of the world I briefly became part of.

Carl Mika and colleagues make an ontological distinction between wording and worlding. We constitute our understanding of the world not only through language and discursive practice but also through being in it. Although the walk can only be conveyed here through language, or wording, the immediacy of the diary (lightly edited for clarity) seems to be a way of conveying something of the worlding that was necessary for me to work with Tshaukuesh on her book and also to write this book. It was my first experience of Tshaukueshs world, of living on Innu land on her terms. Excerpts from notes and recordings as well as narrative vignettes throughout the book are included for the same reason. Another reason for presenting the diary here is that Tshaukuesh wanted me to include some of its stories in my bookspecifically the stories about the times we laughed and had fun together. Those stories didnt seem to fit anywhere else in this book, but a reminder of our shared laughter seems a good thing to include in the introduction.

Nutshimit Diary (2008)

March 11

We set out from Sheshatshiu walking, around 11:00 a.m. in bright sunshine, about twenty below zero. Tshaukuesh; three young Innu men: Pun, Mashan, and her grandson Kaputshet; Ming, a social worker from Singapore who is going to work in the other Labrador Innu community, Natuashish; Kari, an Akaneshau friend and longtime supporter of Tshaukuesh; Jerry, a photographer from Alberta; Tshaukueshs five-year-old grandson, Manteu; three dogs (I only know the names of two: Ukauiak and Blackie); and me. Were hauling wooden toboggans piled with our possessions, covered in tarps and bound with rope, except for Jerry, who has two boat-like plastic sleds with an elaborate harness.

![Stefan Baumgartner [Stefan Baumgartner] - Front-End Tooling with Gulp, Bower, and Yeoman](/uploads/posts/book/120519/thumbs/stefan-baumgartner-stefan-baumgartner-front-end.jpg)