Contents

Guide

WORDS IN AIR

THE COMPLETE CORRESPONDENCE BETWEEN

ELIZABETH BISHOP

AND ROBERT LOWELL

EDITED BY THOMAS TRAVISANO

WITH SASKIA HAMILTON

Farrar, Straus and Giroux / New York

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

FOR ELIZABETH BISHOP 4

by Robert Lowell, from History

The new painting must live on iron rations,

rushed brushstrokes, indestructible paint-mix,

fluorescent lofts instead of French plein air.

Albert Ryder let his crackled amber moonscapes

ripen in sunlight. His painting was repainting,

his tiniest work weighs heavy in the hand.

Who is killed if the horsemen never cry halt?

Have you seen an inchworm crawl on a leaf,

cling to the very end, revolve in air,

feeling for something to reach to something? Do

you still hang your words in air, ten years

unfinished, glued to your notice board, with gaps

or empties for the unimaginable phrase

unerring Muse who makes the casual perfect?

INTRODUCTION:

WHAT A BLOCK OF LIFE

In July 1965 the great mid-century American poet Robert Lowell (1917 1977), who had recently weathered a controversy that brought him into widely publicized opposition to the nations president, wrote affectionately to his poetic peer and close friend Elizabeth Bishop (19111979) from his summer retreat in Castine, Maine, How wonderful you are Dear, and how wonderful that you write me letters In this mid-summer moment I feel at peace, and that we both have more or less lived up to our so different natures and destinies. What a block of life has passed since we first met in New York and Washington! Two years earlier, when their correspondence was briefly interrupted, Lowell acknowledged that I think of you daily and feel anxious lest we lose our old backward and forward flow that always seems to open me up and bring color and peace. Lowell told Bishop in 1970 that you [have] always been my favorite poet and favorite friend, and the feeling was surely mutual. For her part Bishop, with her characteristic blend of directness and wry humor, urged Lowell, Please never stop writing me lettersthey always manage to make me feel like my higher self (Ive been re-reading Emerson) for several days

Through wars, revolutions, breakdowns, brief quarrels, failed marriages and love affairs, and intense poetry-writing jags, the letters kept coming. For these were not merely intimate friends, ready to share each others lives with all their piquant and painful and funny moments, but eager readerseager for the next letter, eager for the next poem. For each, personally as well as artistically, these letters became a part of their abidance: a part of that huge block of life they had lived together and apart over thirty years of witty and intimately confiding correspondence.

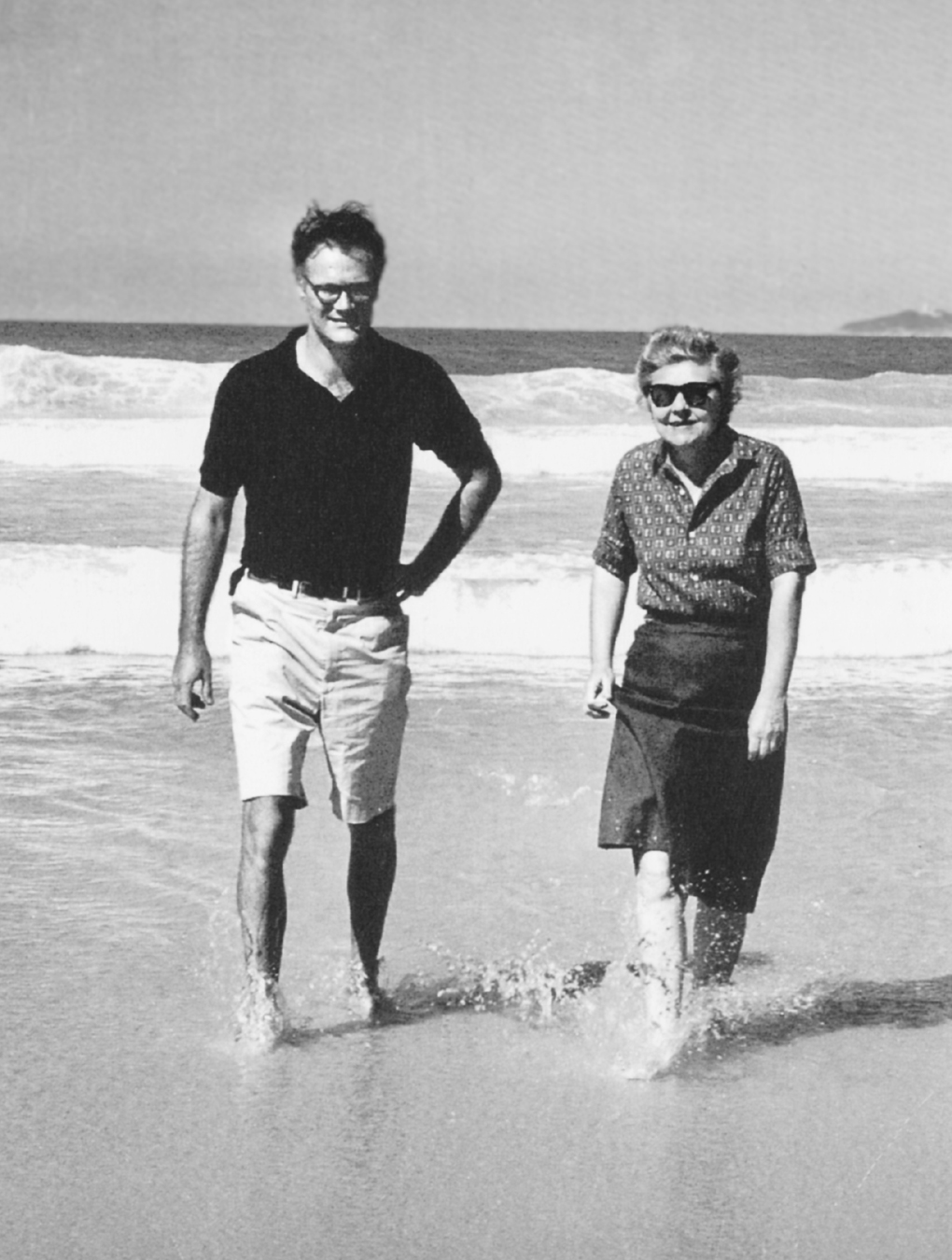

Bishop and Lowell began their lifelong exchange of letters after meeting at a New York dinner party hosted by Randall Jarrell in January 1947. When Jarrell, a gifted poet and the most discerning poetry critic of his age, introduced his old friend Robert Lowell to his new friend Elizabeth Bishop, he was bringing together the two American poets of his generation whom he most admired. The painfully shy Bishop, so often anxious and tongue-tied when among the literati, immediately felt at home with this most imposing of literary lions. Once the letters started coming, any hint of initial stiffness quickly gave way to that easy backward and forward flow. The exchange continued for the next three decades, ending only with Lowells death in 1977. Bishops own death followed two years later, but not before she had written North Haven, the most touching and incisive elegy Lowell ever received: Fun, Bishop wrote of her sad friend, it always seemed to leave you at a loss Yet although both Lowell and Bishop lived lives of some disorder colored by early sorrow, each was clearly having fun with letters as frequently amusingand often downright hilariousas these. Indeed, the droll give-and-take of their affectionate serve and volley is perhaps the letters most surprising and engaging feature. This complete collection of the letters between them extends by more than three hundred letters the published canon of their mutual exchange to be found separately in their selected correspondence: Bishops One Art: Letters (1994), edited by Robert Giroux, and The Letters of Robert Lowell (2005), edited by Saskia Hamilton. The back-and-forth interchange recorded in the present volume provides a window of discovery into the human and artistic development of two brilliant poets over their last and most productive three decades.

Although Bishop confessed to Lowell in a 1975 letter that she had been almost too scared to go to that fateful 1947 meeting, in Lowell she discovered an artistic counterpart whose individuality, verbal flair, and dedication to craft mirrored her own. And the letters themselves are unique. For the artistic distinction of the correspondents, for the unfolding intimacy of the interchange, for its sustained colloquial brilliance of style (with neither poet ever on stilts), for its keen observation of both the ordinary and the extraordinary spiced with a wealth of literary and social history and a smorgasbord of literary gossip, it is hard to think of a parallel.

As the correspondence began in 1947, Bishop was thirty-six and Lowell had recently turned thirty. David Kalstone, in his groundbreaking Becoming a Poet: Elizabeth Bishop with Marianne Moore and Robert Lowell (1989), rightly observes that they could not have met at a better moment. As poets, each had lately published a prizewinning first volume and was achieving substantial recognition for the first time. Bishops North & South (1946) had won the Houghton Mifflin Poetry Prize Fellowship, which included publication and a cash prize, for a book manuscript that triumphed over more than eight hundred rival submissions. Lowells Lord Wearys Castle (1946), which included new poems as well as extensive revisions from his 1944 small press Land of Unlikeness, had wonstill more impressivelythe Pulitzer Prize, making him one of the youngest poets ever to receive that award. Indeed, while both poets would receive many public honors, including a Pulitzer for Bishop in 1956, Lowell would, throughout their lifetimes, continue to enjoy a public reputation that exceeded his friends. One prominent critic, Irvin Ehrenpreis, an admirer of both poets, dubbed their era The Age of Lowell. Lowell appeared on a 1967 Time magazine cover and was regularly featured in other mainstream media not only for his poetry but for his left-of-center political interventions and for a life marked by widely publicized mental breakdowns. Bishop, by contrast, shunned publicity, was retiring by temperament, and lived for long periods in Key West or Brazil, remote from the major American cultural centers, and her work was intensely prized by a narrower circle. Bishop tended to be thought of while living as, in John Ashberys now-famous phrase, a writers writers writer. In the years since her death, however, Bishops reputation has risen dramatically, fully catching up with Lowells, and in the eyes of some, surpassing it. These admiring friends are now linked in many readers mindsas they were in Jarrells six decades beforeas perhaps the two outstanding American poets of their talented mid-century generation.