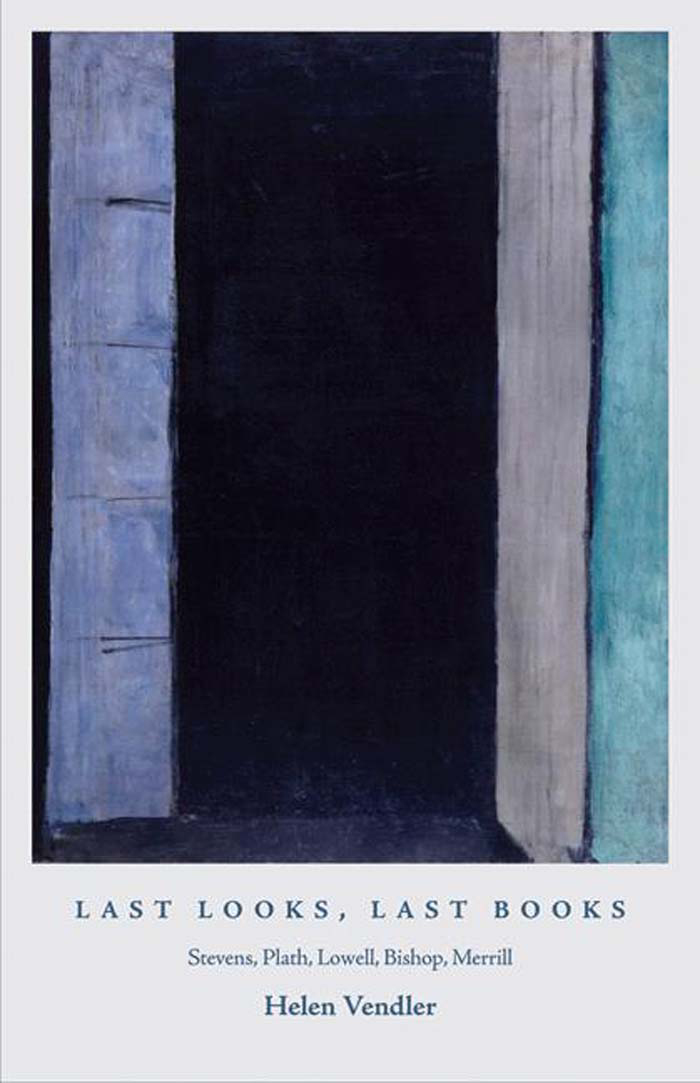

LAST LOOKS, LAST BOOKS

LAST LOOKS, LAST BOOKS

Stevens, Plath, Lowell, Bishop, Merrill

Helen Vendler

THE A. W. MELLON LECTURES IN THE FINE ARTS, 2007 NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON BOLLINGEN SERIES XXXV: 56

Princeton University Press

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2010 Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington

All Rights Reserved

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

This is the fifty-sixth volume of the A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts, which are delivered annually at the National Gallery of Art, Washington. The volumes of lectures constitute Number XXXV in Bollingen Series, sponsored by the Bollingen Foundation.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Vendler, Helen, 1933

Last looks, last books : Stevens, Plath, Lowell, Bishop, Merrill / Helen Vendler.

p. cm. (The A.W. Mellon lectures in the fine arts ; 2007) (Bollingen series ; XXXV, 56)

ISBN 978-0-691-14534-1 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. American poetry20th centuryHistory and criticism. 2. Death in literature. I. Title.

PS310.D42V46 2010

811'.5093548dc22 2009039549

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Adobe Jenson Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

press.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

FOR DAVID, MY BELOVED AND STEADFAST SON

Onely a sweet and virtuous soul,

Like seasond timber, never gives;

But though the whole world turn to coal,

Then chiefly lives.

GEORGE HERBERT

Contents

_________

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to all those at the National Gallery of Art who honored me by the invitation to give the Mellon Lectures of 2007 and by their personal kindness to me during the period of the lectures: Earl A. Powell III, Director of the Gallery; Elizabeth Cropper, Dean of the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts; Therese OMalley, Associate Dean of CASVA; David Brown; and Andrew Drabkin. I enjoyed very much not only the presentation of the lectures but also the social occasions surrounding them, as well as the seminar with the Fellows of CASVA.

As I wrote these lectures, I profited from month-long residencies at the National Humanities Center (the Assad Meymandi Residency) and the American Academy of Berlin. I thank Dr. Meymandi; Geoffrey Harpham, Director of the National Humanities Center; Kent Mullikin, Executive Director of the Humanities Center; and Gary Smith, Executive Director of the American Academy of Berlin for their generous welcome. I was aided in writing these lectures not only by my compensation as Mellon Lecturer but also by research funds from the Department of English at Harvard (the Hyder Rollins Fund) and from my research fund as a University Professor.

I thank Steven Yenser of UCLA for our conversation about James Merrills difficult poem, The Instilling.

I am indebted to Kristin Lambert, my assistant, for continued help in preparing the final manuscript, and to Hanne Winarsky of Princeton University Press for helping this book into print. I also thank Ellen Foos and Dalia Geffen at Princeton.

LAST LOOKS, LAST BOOKS

1

Introduction: Last Looks, Last Books

There is a custom in Ireland called taking the last look. When you find yourself bedridden, with death approaching, you rouse yourself with effort and, for the last time, make the rounds of your territory, North, East, South, West, as you contemplate the places and things that have constituted your life. After this last task, you can return to your bed and die. W. B. Yeats recalls in letters how his friend Lady Gregory, dying of breast cancer, performed her version of the last look. Although for months she had remained upstairs in her bedroom, three days before she died she arose from her chairshe had refused to take to her bedand painfully descended the stairs, making a final circuit of the downstairs rooms before returning upstairs and finally allowing herself to lie down. And Yeats himself, a few years later, took his last look in a sonnet called Meru, which cast a final glance over all his cultural territory: Egypt and Greece, good-bye, and good-bye, Rome!

In many lyrics, poets have taken, if not a last look, a very late look at the interface at which death meets life, and my topic is the strange binocular style they must invent to render the reality contemplated in that last look. The poet, still alive but aware of the imminence of death, wishes to enact that deeply shadowed but still vividly alert moment; but how can the manner of a poem do justice to both the looming presence of death and the unabated vitality of spirit? Although death is a frequent theme in European literature, any response to it used to be fortified by the belief in a personal afterlife. Yet as the conviction of the souls afterlife waned, poets had to invent what Wallace Stevens called the mythology of modern death. In the pages that follow, I take the theme of death and the genre of elegy as given and focus instead on the problem of style in poems confronting not death in general, nor the death of someone else, but personal extinction. I draw my chief examples of such poetry from the last books of some modern American poets: Wallace Stevens, Sylvia Plath, Robert Lowell, Elizabeth Bishop, and James Merrill. The last books of other American poetsJohn Berryman, A. R. Ammonscould equally well have been chosen, but the poems I cite illustrate with particular distinction both the rewards and the hazards of presenting life and death as mutually, and demandingly, real within a single poems symbolic system.

Before I come to describe pre-modern practice in such poems, I want to illustrate very briefly in two poets, Stevens and Merrill, what I mean by the problem of style in a poem that wishes to be equally fair to both life and death at once. Both poets show style as powerfully diverted from expected norms by the stress of approaching death. The first of these poems is by Wallace Stevens, and it is called The Hermitage at the Center. (Even its title is baffling; the poem has no hermitage and no hermit, at least at first glance):

THE HERMITAGE AT THE CENTER

The leaves on the macadam make a noise

How soft the grass on which the desired

Reclines in the temperature of heaven

Like tales that were told the day before yesterday

Sleek in a natural nakedness,

She attends the tintinnabula

And the wind sways like a great thing tottering

Of birds called up by more than the sun,

Birds of more wit, that substitute

Which suddenly is all dissolved and gone

Their intelligible twittering

For unintelligible thought.

And yet this end and this beginning are one,

And one last look at the ducks is a look

At lucent children round her in a ring.

Stevens has here presented a poem that seems unintelligible as one reads it line by line. It contains, as we eventually realize, two poems that have been interdigitatedone of death, one of life, converging in a joint coda. The first poemthat of death, of seasonal end, of unintelligible extinctioncan be seen by reading in succession the opening lines of the first four tercets: