Contents

by Frieda Hughes

M Y MOTHER, THE POET S YLVIA P LATH , was born on 27 October 1932 in the Massachusetts Memorial Hospital in Boston in the United States. She lived with energy, passion and a thirst for knowledge, which she directed into her literary and artistic endeavours until her suicide on 11 February 1963.

Although she retained our Devonshire family home after she and my father, the poet Ted Hughes, separated in October 1962, my mother felt the need to be in London. She rented a maisonette at 23 Fitzroy Road, where she lived with my younger brother, Nicholas, and me, for just eight weeks before she died.

Now well known for her semi-autobiographical novel The Bell Jar , which was published under the pseudonym Victoria Lucas a few weeks before her death in 1963, it was poetry that first made my mothers name when her collection, Ariel , was published to posthumous acclaim in 1965. It was edited by my father using poems from the manuscript that my mother left on her desk at the time of her death.

In 2004, Faber and Faber in the UK and HarperCollins in the US published Ariel: The Restored Edition , which used my mothers last actual arrangement of her poems. I very much like having both volumes available, as my fathers edition is influenced by his own preferences and what I consider to be his incredibly astute editorial eye, whereas my mothers edition is very much a work in progress, halted in its evolution at the point of her death.

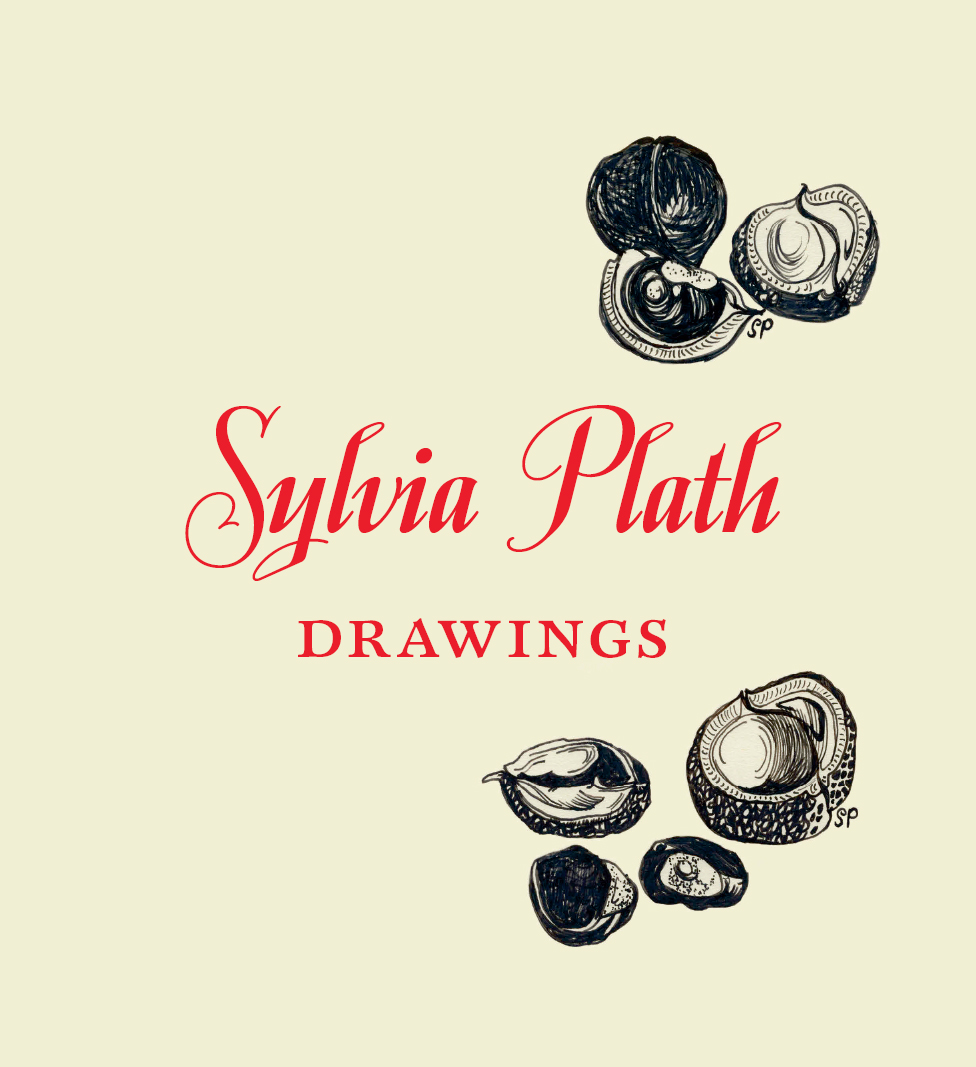

As much as poetry dominated her purpose, however, art was always an important element of my mothers life. As a teenager she was given private art tuition by a Miss Hazelton, and as an adult she wrote in her Yaddo journal (see The Journals of Sylvia Plath published by Faber and Faber in 2000) that she had dreams of grandeur in hoping that the New Yorker might use her illustrations alongside her written work, as the Christian Science Monitor did, giving sanction to my running about drawing chairs and baskets.

Having graduated from Smith College on 6 June 1955, my mother attended Newnham College at Cambridge University from October 1955 to June 1957, reading English on a Fulbright fellowship from the States. While at Cambridge she met and married my father; their wedding took place at 1.30 p.m. on 16 June 1956, by special licence from the Archbishop of Canterbury, in the Church of St George the Martyr, Bloomsbury. They didnt initially make their marriage public knowledge because my mother feared losing her grant.

In June and July 1956 my parents honeymooned first in Paris and Benidorm, before returning to Paris in August, which my mother recorded in some of her sketches. It wasnt until October that year that the couple decided to let Fulbright and Newnham know they were married: fortunately, my mothers fellowship wasnt affected.

In his final collection of poems, Birthday Letters , my father mentions my mothers drawings; in his poem Your Paris my mother draws the Paris roofs, a traffic bollard, a bottle, and him too. In his poem Drawing he describes how the very act calmed my mother, and how she became focused and still, and how, as the hours burned away the objects she rendered were tortured into their last position, and the whole scene was imprisoned, for ever.

My mother frequently recorded her literary and artistic evolution in her letters and her diaries; in a letter to my father dated 7 October 1956 (Sunday morning), which is included in this book, she describes sketching cows in Grantchester Meadows only the day before. This was one of several letters my mother wrote to my father from Cambridge during their periods of self-imposed separation, which were intended to maintain the illusion that they were not married.

In a letter to her friend from Smith College, Marty (Marcia) Brown Stern, dated Saturday 15 December 1956, she wrote effusively about her new husband, telling Marty, He started me writing & drawing again after a bad winter... She frequently credited my father with inspiring her to creativity when she became stuck or felt herself to have lost direction.

The art of others was also inspiration for her poems; following a request from ARTnews in 1958, she wrote poems inspired by the works of her favourite artists. At the time she was teaching freshman English at Smith College, where she had once been a student, and was also auditing an art history course taught by Smith professor Mrs Van der Poel.

On 22 March 1958 in a letter to her mother, my mother was ebullient: Ive discovered my deepest source of inspiration, which is art: the art of the primitives like Henri Rousseau, Gauguin, Paul Klee, and De Chirico. I have got out piles of wonderful books from the Art Library (suggested by this fine Modern Art Course Im auditing each week) and am overflowing with ideas and inspirations, as if Ive been bottling up a geyser for a year.

My mother wrote two poems inspired by de Chirico, two by Rousseau and four by Klee. While working on these poems she discussed her influence in an interview on 18 April 1958 that she and my father recorded with Lee Anderson in Springfield, Massachusetts: I have a visual imagination. For instance, my inspiration is paintings and not music when I go to some other art form... I see these things very clearly.

Some of my mothers early artwork, together with sketches and drawings over letters and postcards, is to be found with her archive in the Mortimer Rare Book Room at Smith College, Massachusetts, and at the Lilly Library, Indiana University, Bloomington. The pictures in this book, however, are the collection that my father gave to my brother and me before his death on 28 October 1998; they are mostly from 1956, the year of my parents marriage, and follow my personal arrangement as dates of composition cannot be determined in all cases.

Although my father had divided the drawings between us, my brother asked that I keep them together and look after them until we could, in the fullness of time, organise an exhibition for them. But life got in the way and the years passed, and then, tragically, on 16 March 2009 my brother also committed suicide.

It wasnt until November 2011 that the drawings finally went on show to be sold at the Mayor Gallery, Cork Street, London.

F RIEDA H UGHES , 25 March 2013

Sunday morning

October 7, 1956

Dearest love Teddy...

A brilliant gray morning... sweet gift of an extra hour last nightwhy cant they do that every day? All the new little girls including Janeen, Dina, Jess, Marie, left for church this morning after breakfast armed with bibles talking about catching the service as if it were a bus. I beamed benevolently at them over my third atheistic cup of coffee and ate my existentialist egg; they really are very sweet, but, my god, so young, so young. In twenty days I shall have completed my 24th year and begun my 25thI am cruel in putting it this way, but it is true; a quarter of a century gone to pot; and please the lord let there be three more quarter centuries all blessed by your presence, come day, come night, come hurricane and holocaust...

O Teddy, how I repent for scoffing in my green and unchastened youth at the legend of Eves being plucked from Adams left rib; because the damn storys true; I ache and ache to return to my proper place, which is curled up right there, sheltered and cherished; I am sure you, as a man, will hack out some sort of self-sufficience in this year, missing only one rib; but I; my whole sense of being is blasted by your absence; and I am again having the most terrible of nightmares, no matter how stoically I go about in the day; it all catches up at night; last night it was you and youterribly realistic, and then this gruesome series of Ethiopian tribal ceremonies all centering about totems, purifying rituals, and most terrible; perhaps over all was the epigraph of Augustines I read yesterdayVerily some have become eunuchs for Thy sake. God, its terrible; the daily world I can wrest, amid great hurt and void, more and more to my will, but I get to dread the night so; before supper I can feel it coming on me, and I get cloyed at supper and dont want to eat, and rush out into the dark, and walk blindly; and then read, putting off bed and putting it off; and then those damn nightmares.