THE

BELL JAR

Sylvia Plath

for Elizabeth and David

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword

by Frances McCullough

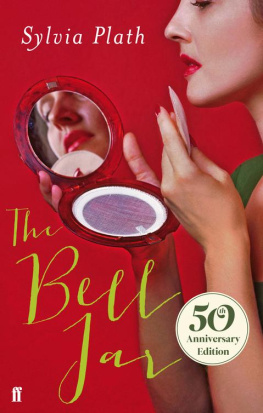

You might think that classics like The Bell Jar are immediately recognized the moment they reach a publishers office. But publishing history is rife with stories about classic novels that barely squeaked into print, from Nightwood to A Confederacy of Dunces, and The Bell jar is one of them. Its hard to say whether, if Sylvia Plath had lived--shed be a senior citizen on her sixty-fifth birthday, October 27th, 1997--the novel would ever have been published in this country: Certainly it would not have been published until her mother died, which would have kept it from our shores until the early 90s. And by that time, Plath might have become a major novelist who might see her first book in a quite different light.

But of course Plath did die a tragic death at the age of thirty, and the books subsequent history has everything to do with that fact. The first time her manuscript came into the offices at Harper and Row in late 1962 it was under the auspices of the Eugene F. Saxton Fellowship, a grant affiliated with the publishing house that supported the writing of the book. The grant required Plath to submit the final manuscript to the Saxton committee. Two Harper editors, both older women with a special interest in poetry, read the novel in hopes of getting first crack at a new voice in the literary world--but both of them found it disappointing, juvenile and overwrought. In effect, they rejected the book, though it hadnt been offered to them officially, and in fact Plath was quite insistent that it shouldnt be published in America because its roman--clef elements would be so hurtful to her family and their friends.

Actually, Plath already had an American publisher. Knopf had bought her first book of poems, The Colossus (1962), an event that triggered the first outpouring of prose that became The Bell jar. For a long time Plath had been thinking about writing a novel; her ambitions to break into the slicks, especially the Ladies Home journal) were constantly on the back burner as she concentrated on her poems. Addressing her as Dear Mrs. Hughes, the Saxton Fellowship had turned down her poetry manuscript, the one that became The Colossus) so it must have been a particular point of pride when they later accepted The Bell jar project.

She also had a British publisher: William Heinemann Limited had published The Colossus in the fall of 1960, and agreed to publish The Bell jar) under the pseudonym Victoria Lucas (though everyone in literary London knew Plath was the author), in January 1963--which turned out to be just a few weeks before Plaths death. Reviews were lukewarm, and Plath was deeply stung by them. But she had already begun another novel the previous spring, and by her mothers account, there was yet another finished one that went up in a bonfire one day when Plath was in a rage. Although she wasnt as surefooted in her fiction as she was in poetry, she planned to write novel after novel once her book of poems (Ariel) was finished.

But by the time The Bell Jar came out in London, Plath was in extremis; her marriage to poet Ted Hughes was over, she was in a panic about money, and had moved to a bare flat in London with her two small children in the coldest British winter in a hundred years. All three of them had the flu, there was no phone, and there was no help with child care. She was well aware of the brilliance of the poems she was writing--and in fact A. Alvarez, the leading critic of the day, had told her they deserved a Pulitzer. But even that knowledge didnt save her from the dreaded bell jar experience, the sudden descent into deep depression that had triggered her first suicide attempt in the summer described in the novel. A number of the same elements were in place this time: the abrupt departure of the central male figure in her life, critical rejection (Plath had not been accepted for Frank OConnors writing class at Harvard that Bell Jar summer), isolation in new surroundings, complete exhaustion.

Plaths suicide on February 11, 1963 brought her instant fame in England, where she had made occasional appearances on the BBC and was beginning to be known through her publications. But she was still not well known here in her native land, and there was no sign that she would become not only the last of the major poets read widely, but also a feminist heroine whose single published novel had spoken directly to the hearts of more than one generation.

When I first arrived at Harper in the summer of 1964, there was no actual job for me--Id been reading for the Saxton Prize novel contest, the latest incarnation of the Fellowship, on a temporary basis, and Id been put on staff simply because, as my new boss put it, If youre as good as we think you are, youll figure out something to do. I looked around; the poetry editor, who was one of the readers of The Bell Jar who hadnt liked it, was retiring. I did a little checking and discovered that virtually every poet in America was unhappy with his or her publisher. This seemed to me a good opportunity to attract some stars to our list, so I proposed hiring a poetry scout--my candidate was Donald Hall. I sent off a memo to Cass Canfield, the publisher, who thought this was a fine idea.

When Don went to London later that year, Ariel had just been published and Don was elated; he bought a copy of the book and sent a cable urging us to publish it. Knopf was of course interested too, but theyd quickly hit a sticking point. None of their poets--and they had a fine list--had ever been paid over $250 as an advance against royalties for a book of poems, and it was unthinkably unfair, they felt, to make an exception for Plath. Meantime, Don pointed out to Plaths husband and executor Ted Hughes that it would make perfect sense to publish Ariel with Harper since Hughes himself was published there, so the nod was going in our direction.

I knew about Plath; her odd name had been ringing in my head ever since Id first heard it from A. Alvarez, whod been teaching at Brandeis in my graduate school days. But these poems profoundly affected me as none of her New Yorker poems or Colossus poems had. Although there was opposition inside the house from some quarters, who felt the poems were too sensational, eventually Roger Klein, a young editor, and I were allowed to buy the book for $750--a small sum, noted editor in chief Evan Thomas--to give the young people their head.

From the moment Ariel appeared in print, it was a sensation, with a double-page spread in Time magazine setting off a frenzy. Women were joining consciousness-raising groups, and Plath was often the center of the discussion. After her death, Ted Hughes, who inherited the copyright on all her work, published and unpublished, had assured her mother that The Bell Jar would not be published in America during Mrs. Plaths lifetime. But the demand for more Plath had led to bootleg copies of the novel coming in from England; at least two bookstores in New York carried the book and sold it briskly.

There was yet another quirk in the publishing history of The Bell Jar, a copyright snag. Because it had been published abroad originally by an American citizen, and had not been published in America within six months of foreign publication or registered for copyright in the United States, it fell under a provision (since nullified) called Ad Interim, which mean it was no longer eligible for copyright protection in America. This had been a closely guarded secret, but one day in 1970 I had a phone call from Juris Jurjevics, an old friend at another publishing house, alerting me that John Simon at Random House was aware of the copyright situation and was planning to publish the book. This was horrifying; I called Simon and explained to him that the only reason the book hadnt been published was out of respect for Mrs. Plaths feelings, that we had an agreement to publish it if she changed her mind or if she died, and that it was unconscionable for him to steal this book. To my utter astonishment, he agreed, and said he would cancel the publication.