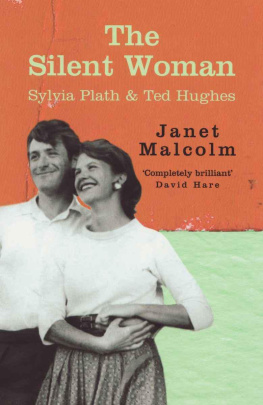

Acclaim for JANET MALCOLM S

The Silent Woman

Not since Virginia Woolf has anyone thought so trenchantly about the strange art of biography. We follow along as Malcolm crisscrosses the United States and Britain in search of Plaths friends, lovers, neighbors, biographers. What makes these exchanges so fascinating is that Malcolm herself has the novelists noticing eye that she has attributed to Plath.

Christopher Benfey, Newsday

There is more intellectual excitement in one of Malcolms riffs than in many a thick academic tome. She is among the most intellectually provocative of authors able to turn epiphanies of perception into explosions of insight. Controversy trails her like clouds of glory.

David Lehman, Boston Globe

It is the best-written and most stirring polemic of the year. Completely brilliant.

David Hare, London Times

The Journalist and the Murderer was a deeply thoughtful exposure of the moral problems of in-depth journalism. [The Silent Woman] contains some of the best thinking I know on both the practical and the philosophical problems of biography.

Bernard Crick, New Statesman & Society

A brilliant literary tour de force that reads like a thriller.

Anna Fels, The Nation

The Silent Woman is a book that sets out to be provocative and succeeds. It is superbly written, flowing like a piece of music from theme to theme, recapitulating here, changing key there, always disguising the complexity of its underlying construction.

Lucasta Miller, The Independent

The magnetic pull of Sylvia Plaths story, and Malcolms personal attraction to it despite her proclaimed scruples, produce the tension that makes The Silent Woman so fascinating. The book is a tour de force, the best thing Malcolm has ever done.

Elaine Showalter, Los Angeles Times Book Review

[Malcolm is] one of the few living writers who practice the New Yorker profile in the grand manner. She has been able to carry the genre to the length it needs; and she possesses a further and a more unusual distinction. In America, she is the only reporter who writes books on culture that show the mark of a participant and not a spectator.

David Bromwich, The New Republic

My heart sinks when I see yet another book about Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes, and then rises again when I realize that the author is Janet Malcolm. In spite of the fact that there have been five biographies of Sylvia Plath along with other shorter accounts of her life and poetry, Malcolms brief, pungent contribution is provocative, original and welcome. I dont think any reader of the book will ever be able to regard the genre of biography in quite the same light again.

Anthony Storr, London Times

JANET MALCOLM

The Silent Woman

Janet Malcolm is the author of Diana and the Nikon: Essays on the Aesthetics of Photography, Psychoanalysis: The Impossible Profession, In the Freud Archives, The Journalist and the Murderer, and The Purloined Clinic. She lives in New York City.

ALSO BY JANET MALCOLM

Diana and Nikon

Psychoanalysis: The Impossible Profession

In the Freud Archives

The Journalist and the Murderer

The Purloined Clinic

Copyright 1993, 1994 by Janet Malcolm

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, in 1994.

Originally published, in different form, in The New Yorker.

Owing to limitations of space, all acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published and unpublished material will be found on .

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition as follows:

Malcolm, Janet.

The silent woman : Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes / by Janet Malcolm

p. cm.

1. Plath, Sylvia. 2. Women poets, AmericanBiographyHistory and criticism. 3. Women poets, American20th centuryBiography. 4. Executors and administratorsGreat Britain. 5. Biography as a literary form. 6. Hughes, Ted, 1930 .

7. Canon (Literature) I. Title.

PS 3566. L 27 Z 776 1994

811.54dc2o

[ B ] 93-33848

eISBN: 978-0-307-83061-6

v3.1_r1

To Gardner

The reporter and the reported have duly and equally to understand that they carry their life in their hands. There are secrets for privacy and silence; let them only be cultivated on the part of the hunted creature with even half the method with which the love of sportor call it the historic senseis cultivated on the part of the investigator. They have been left too much to the natural, the instinctive man; but they will be twice as effective after it begins to be observed that they may take their place among the triumphs of civilisation. Then at last the game will be fair and the two forces face to face; it will be pull devil, pull tailor, and the hardest pull will doubtless provide the happiest result. Then the cunning of the inquirer, envenomed with resistance, will exceed in subtlety and ferocity anything we today conceive, and the pale forewarned victim, with every track covered, every paper burnt and every letter unanswered, will, in the tower of art, the invulnerable granite, stand, without a sally, the siege of all the years.

HENRY JAMES , George Sand (1897)

Liz Taylor is getting Eddie Fisher away from Debbie Reynolds, who appears cherubic, round-faced, wronged, in pin curls and house robeMike Todd barely cold. How odd these events affect one so. Why? Analogies?

SYLVIA PLATH , Journals, September 2, 1958

Contents

P ART O NE

I

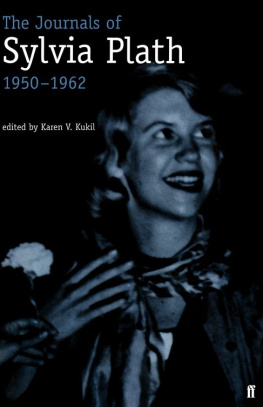

T ED HUGHES wrote two versions of his foreword to The Journals of Sylvia Plath, a selection of diary entries covering the years between 1950 and 1962. The first version (the one that appears in the book, published in 1982) is a short, lyrical essay constructed on a single Blakean themethe theme of a real self that finally emerged from among Plaths warring false selves and found triumphant expression in the Ariel poems, which were written in the last half year of her life and are the whole reason for her poetical reputation. In Hughess view, her other writingsthe short fiction she doggedly wrote and submitted, mostly unsuccessfully, to popular magazines; her novel, The Bell Jar; her letters; her apprentice poems, published in her first collection, The Colossuswere like impurities thrown off from the various stages of the inner transformation, by-products of the internal work. He writes about a remarkable prefigurative moment:

Though I spent every day with her for six years, and was rarely separated from her for more than two or three hours at a time, I never saw her show her real self to anybodyexcept, perhaps, in the last three months of her life.

Her real self had showed itself in her writing, just for a moment, three years earlier, and when I heard itthe self I had married, after all, and lived with and knew wellin that brief moment, three lines recited as she went out through a doorway, I knew that what I had always felt must happen had now begun to happen, that her real self, being the real poet, would now speak for itself, and would throw off all those lesser and artificial selves that had monopolized the words up to that point. It was as if a dumb person suddenly spoke.