More great titles from PAVILION

Tap on the titles below to read more

| @PavilionBooks |

| Pavilion Books |

| www.pavilionbooks.com |

Preface

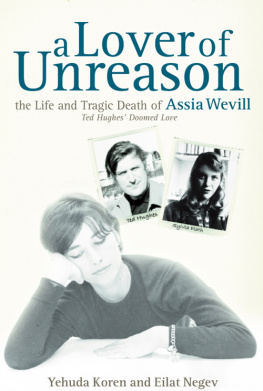

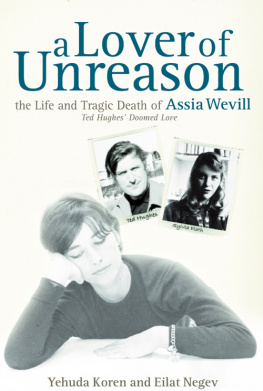

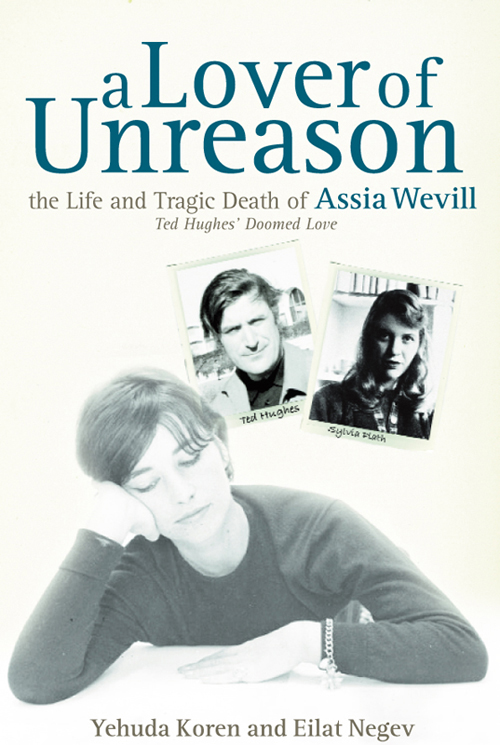

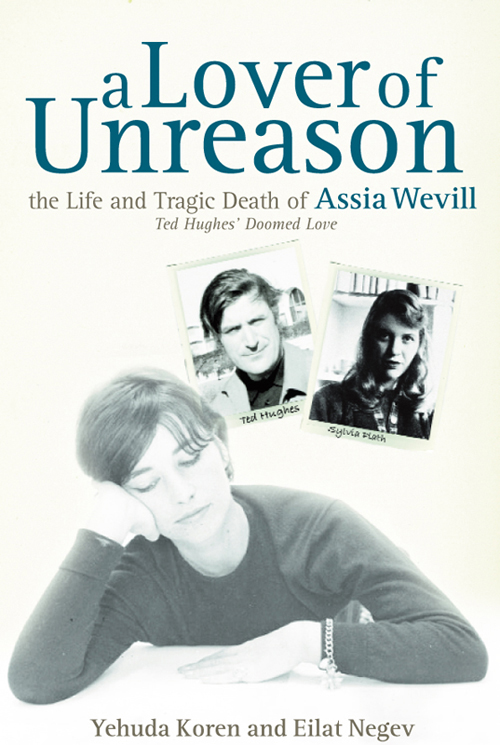

Twenty years ago we were leafing through a book by the Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai, when we chanced upon a poem entitled The Death of Assia G. I cant understand your death in London, Amichai wrote, and we were curious to know who this woman was and what she was to him that he vowed to publicise her death.

We called him the next day.

Amichais answer was laconic and mystifying: Assia was the beloved of his best friend Ted Hughes and an ex-Israeli who died tragically in 1969. The G stood for her maiden name, Gutmann. This set us on our quest.

Ever since, we have been tracing the many facets of Assia Wevills story, and have published a number of features about her in major British, German and Israeli newspapers. In October 1996, we had a world-exclusive interview with Ted Hughes the only personal one he ever granted. For once, he spoke about Assia.

Like Sylvia Plath, Assia shared her life with Hughes for six years, and she, too, bore him a daughter. Still, she has been effectively written out of his story. Any influence she may have exerted on him or his work has been diminished or dismissed. The story of the ultimately tragic failure of his marriage to Sylvia Plath has been related in numerous books and articles from one of two conflicting points of view: his or hers. Either way, Assia was reduced to the role of a she-devil, enchantress, Lilith, Jezebel, the woman alleged to have severed the union of twentieth-century poetrys most celebrated couple.

Assia Wevill was a complex person, born to dichotomies. Her remarkable life evinces both the limitations and the possibilities of a gifted, independent-spirited, ambitious woman in the mid-twentieth century. To gain a variety of perspectives on her character and to amass as much detail and as many dimensions as possible we have interviewed seventy people, including her sister and brother-in-law. Her schoolfriends in Tel Aviv and the British soldiers who dated her there have contributed substantially to our sense of the beautiful, rebellious teenage Assia. Her three husbands have provided insights into the captivating woman she was. Intimate friends of Assia and her colleagues from advertising, as well as friends of Hughes and Plath, have shared with us their memories of Assia in London in the sixties.

Our intensive search for new primary source material has not gone unrewarded and in its course we have uncovered a wealth of documents and private papers, many of which were not known to exist. We worked in numerous archives around the world, and gathered new findings from the Hughes and Plath archives and from those of prominent poets who corresponded with them. Some of the material was censored until recently.

The examination of this material in conjunction with Assias diaries, letters and poems is of great importance in the understanding of the writing of the protagonists of the book and of the events that surrounded the two suicides. It reveals the inter-relationship of their work and is all the more important for the fact that some of Assia and Plaths writing was destroyed.

A Lover of Unreason charts the emergence of a singular twentieth-century woman. Exotic, cosmopolitan, cultured, she mesmerised men and women alike. Yet she was also a divorcee (thrice), a career woman, the other woman, and a single mother: she openly defied the conventions of a censorious pre-feminist society.

Assia was on a quest to moor herself emotionally and express herself creatively. Yet security would continually elude her, for all her apparent self-assurance, charm and sophistication. At the same time as she strove to free her creative spirit and declare her independence, so she defined herself by, and bound herself to, the men in her life, ultimately to catastrophic effect. In her increasingly obsessional relationship with Hughes, doubt, fear, distrust and humiliation would dog her, and dislodge her. She and Hughes would not marry, they would not find the house that they would make their own. Instead, Assia unmoored, again the nomad, always the mistress or muse would end the journey.

The exquisitely beautiful Assia inspired, or provoked, many epithets in the pursuit of a destiny that took her, via several continents, from dark pre-war Berlin via Tel Aviv, Vancouver and Mandalay, to London in the swinging sixties. In the end, none would prove to be more fitting than the epithet (and epitaph) she chose for herself in her last will and testament: Here lies a lover of unreason and an exile.

Jerusalem, May 2006

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the following sources from which we have drawn and quoted: our interviews with Celia Chaikin, Assia Wevills sister, telephone interview, January 1999, email exchange, January 1999May 2002, interviews in Canada, MayJune 2002, and subsequent emails, letters and telephone calls, July 2002April 2006; Arnold Chaikin, Assias brother-in-law, interviews in Canada, MayJune 2002: the Chaikins kindly provided us with photographs from their family album, as well as with correspondence and documents pertaining to Assia and the Gutmann family; John H Steele, Assias first husband, letter exchange and excerpts from his diary, July 2002January 2004; Richard (Dick) Lipsey, her second husband, interview in Canada, June 2002, and email exchange, July 2002June 2003; his sister, Thirell (Lipsey) Weiss, email exchange, AugustDecember 2002; David Wevill, Assias third husband, interview in Texas, November 2003, and email exchange, September 2002December 2005; Ted Hughes, interview in London on 8 October 1996; Olwyn Hughes, letter exchange, August 2002June 2003; about Assias life in the 1940s, we interviewed Leila Andreas and Wedad Andreas, in Israel, November 2001; Hannah Weinberg-Shalitt, interview in Israel, January 1999; Mira Hamermesh, interview in London, October 2001; Keith and Pam Gems, interview in London, December 2003, and letter exchange, August 2002February 2004, as well as correspondence and photos from the 1940s and 1950s that they have kindly provided us with; John Bosher, telephone interview and email exchange, JulyAugust 2002, as well as excerpts from his diary; Esther Birney, telephone interview, December 2001, and a letter from January 2002; about Assias life in England and Burma in the 1950s, we interviewed Liliana Archibald, in London, March 2003; Alton Becker, email exchange, MarchJuly 2002; Marilyn Corry, email exchange, September 2002; Martin Graham, interview in London, October 2001; Philip Hobsbaum, email exchange, October 2001May 2003; Edward Lucie-Smith, interview in London, October 2001, and email exchange, December 2001 August 2003; Patricia Mendelson, interview in London, September 2001, as well as correspondence and photos of Assia and Shura; Don Michel, email, September 2002; Ian Montagnes, email exchange, SeptemberOctober 2002; Roger Philips, email exchange, November 2001; Peter Porter, interview in London, September 2001, and letters, OctoberDecember 2001; Jo (Reed) Price, email exchange, SeptemberOctober 2002; Kenneth Reed, a letter from November 2002; about Assias life in England and Ireland in the 1960s: Al Alvarez, interview in London, September 2001; Anne (Adams) Alvarez, interview in London, October 2001; Martin Baker, interview in Oxfordshire, October 2001, and email exchange, November 2001January 2004, as well as footage of Assias film and photographs that he took of her and Shura; Kathleen Becker, interview in London, September 2001, as well as a memoir written by her late husband, Gerry Becker; Tom Boyd, telephone interview, September 2004; Anna (Owen) Bramble, interview in London, October 2001; Sue Byrne, email exchange, November 2001; John Chambers, interview in London, September 2001; Douglas Chowns, email exchange, November 2001June 2003; Barrie Cooke, telephone interviews in November 2002 and in March 2004; Janos Csokits, interview in Budapest, March 2006, and letter exchange, December 2003September 2005; Jane Donaldson, email and letter exchange, November 2003February 2004, as well as photographs of Assia; Dan Ellerington, telephone interview, January 2002; Ruth Fainlight, email exchange, JanuaryFebruary 2004; Jonny Gathorne-Hardy, interview in London, October 2001; Michael Hamburger, letters JuneJuly 2002; Brenda Hedden, interviews in England, SeptemberOctober 2001; Guy Jenkin, interview in London, October 2001; Ann Henning Jocelyn, interview in Ireland, March 2005; Robert Jocelyn, Earl of Roden, interview in Ireland, March 2005; Angela Landels, interview in London, October 2001; Richard Larschan, interview in Massachusetts, USA, June 2004, and email exchange, September 2001December 2005; Fay Maschler, interview in London, October 2001; Julia Matcham, interview in London, September 2001, and letters and email exchange, September 2001December 2002; Horatio Morpurgo, email exchange, April 2003; Lucas Myers, email exchange, November 2001December 2003; Hugh Musgrave, interview in Ireland, March 2005; Keith Ravenscroft, email exchange, October 2001; Clarissa Roche, interview in England, September 2001, as well as a copy of the unpublished memoir written by the late Trevor Thomas; Teresa Reilly, telephone interview, April 2005; Philip Resnick, email exchange, April 2004; Chris Roos, interview in London, October 2001; David Ross, interview in London, March 2003; Ann Semple, telephone interview, January 2002; Elizabeth (Compton) Sigmund, interview in England, August 2001, and subsequent email exchange, SeptemberDecember 2001, as well as Assias tapestry letter to Sylvia Plath, and Hughess letters to the Comptons; Ben Sonnenberg, email exchange, August 2002; Royston Taylor, email exchange, November 2001February 2002; John Wainwright, interview in London, October 2001; Daniel Weissbort, interview in London, May 2002, and letter exchange, April 2002September 2005; Fay Weldon, interview in London, September 2001; Chris Wilkins, email exchange, October 2001.

Next page