More great titles from PAVILION

Tap on the titles below to read more

| @PavilionBooks |

| Pavilion Books |

| www.pavilionbooks.com |

Preface

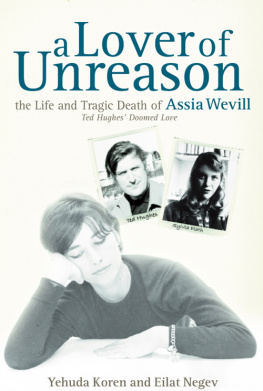

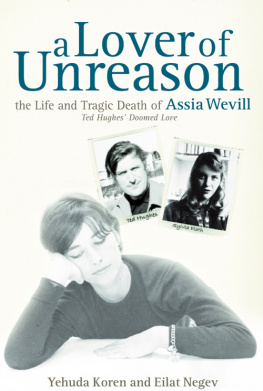

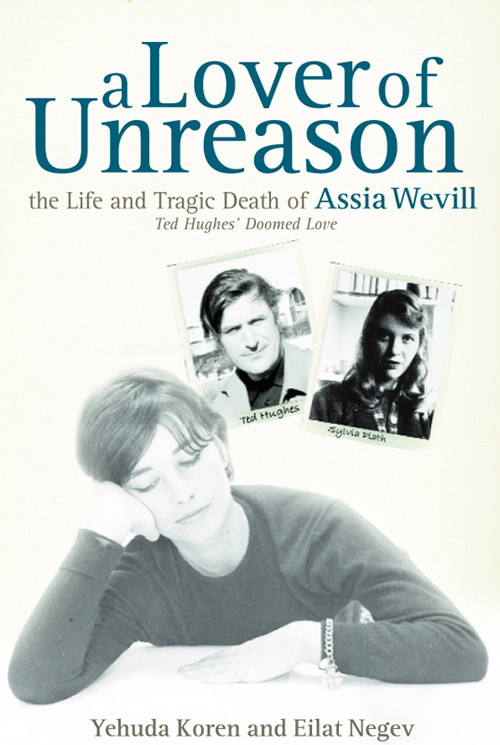

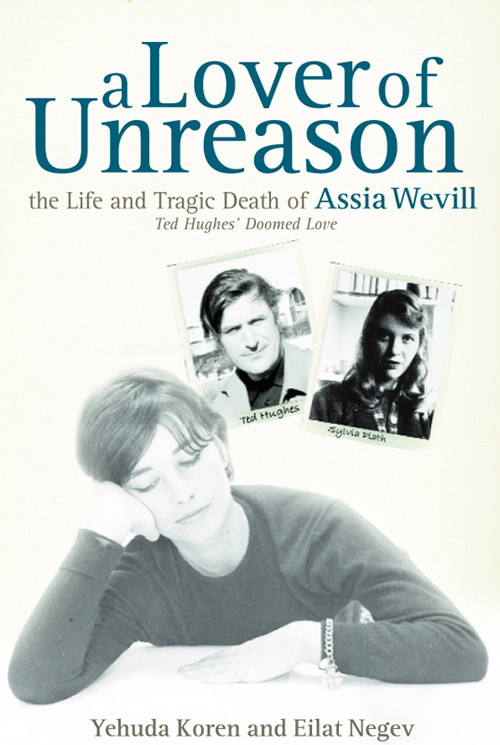

Twenty years ago we were leafing through a book by the Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai, when we chanced upon a poem entitled The Death of Assia G. I cant understand your death in London, Amichai wrote, and we were curious to know who this woman was and what she was to him that he vowed to publicise her death.

We called him the next day.

Amichais answer was laconic and mystifying: Assia was the beloved of his best friend Ted Hughes and an ex-Israeli who died tragically in 1969. The G stood for her maiden name, Gutmann. This set us on our quest.

Ever since, we have been tracing the many facets of Assia Wevills story, and have published a number of features about her in major British, German and Israeli newspapers. In October 1996, we had a world-exclusive interview with Ted Hughes the only personal one he ever granted. For once, he spoke about Assia.

Like Sylvia Plath, Assia shared her life with Hughes for six years, and she, too, bore him a daughter. Still, she has been effectively written out of his story. Any influence she may have exerted on him or his work has been diminished or dismissed. The story of the ultimately tragic failure of his marriage to Sylvia Plath has been related in numerous books and articles from one of two conflicting points of view: his or hers. Either way, Assia was reduced to the role of a she-devil, enchantress, Lilith, Jezebel, the woman alleged to have severed the union of twentieth-century poetrys most celebrated couple.

Assia Wevill was a complex person, born to dichotomies. Her remarkable life evinces both the limitations and the possibilities of a gifted, independent-spirited, ambitious woman in the mid-twentieth century. To gain a variety of perspectives on her character and to amass as much detail and as many dimensions as possible we have interviewed seventy people, including her sister and brother-in-law. Her schoolfriends in Tel Aviv and the British soldiers who dated her there have contributed substantially to our sense of the beautiful, rebellious teenage Assia. Her three husbands have provided insights into the captivating woman she was. Intimate friends of Assia and her colleagues from advertising, as well as friends of Hughes and Plath, have shared with us their memories of Assia in London in the sixties.

Our intensive search for new primary source material has not gone unrewarded and in its course we have uncovered a wealth of documents and private papers, many of which were not known to exist. We worked in numerous archives around the world, and gathered new findings from the Hughes and Plath archives and from those of prominent poets who corresponded with them. Some of the material was censored until recently.

The examination of this material in conjunction with Assias diaries, letters and poems is of great importance in the understanding of the writing of the protagonists of the book and of the events that surrounded the two suicides. It reveals the inter-relationship of their work and is all the more important for the fact that some of Assia and Plaths writing was destroyed.

A Lover of Unreason charts the emergence of a singular twentieth-century woman. Exotic, cosmopolitan, cultured, she mesmerised men and women alike. Yet she was also a divorcee (thrice), a career woman, the other woman, and a single mother: she openly defied the conventions of a censorious pre-feminist society.

Assia was on a quest to moor herself emotionally and express herself creatively. Yet security would continually elude her, for all her apparent self-assurance, charm and sophistication. At the same time as she strove to free her creative spirit and declare her independence, so she defined herself by, and bound herself to, the men in her life, ultimately to catastrophic effect. In her increasingly obsessional relationship with Hughes, doubt, fear, distrust and humiliation would dog her, and dislodge her. She and Hughes would not marry, they would not find the house that they would make their own. Instead, Assia unmoored, again the nomad, always the mistress or muse would end the journey.

The exquisitely beautiful Assia inspired, or provoked, many epithets in the pursuit of a destiny that took her, via several continents, from dark pre-war Berlin via Tel Aviv, Vancouver and Mandalay, to London in the swinging sixties. In the end, none would prove to be more fitting than the epithet (and epitaph) she chose for herself in her last will and testament: Here lies a lover of unreason and an exile.

Jerusalem, May 2006

Prologue

At noon on Sunday, 23 March 1969, Assia Wevill telephoned Ted Hughes at his home, Court Green. They had spent the past five days house-hunting in Yorkshire. On Saturday Assia had returned to her young daughter in London, and he to his children in Devon. For six years they had been trying to set up a home together but every failed attempt drove another wedge between them. They had a vicious quarrel over the phone that culminated with Assia insisting that they should separate for good: the relationship between them was no more than hobbling on and she simply did not believe any longer that he really wanted to be with her. Still, Assia did not slam the door on their future together completely. She remarked that she had spotted an ad for a house to rent in Devon, in the old market town of Barnstaple. Ted asked for the address and promised that he would take a look at it. Assia was not pacified, however, and they resumed arguing until, finally, she told him that her bags were packed and she was going to visit some friends in Dorset for a week. He was not to phone her back, she said, and without waiting for his response, she put down the phone.

Ten minutes later, Ted did phone back, and they continued their squabble. The two of them had endured scores of similar dead-end arguments over the past years and he felt that Assia was reciting her old grievances towards him. In apathy and exhaustion he had repeated his worn-out reassurances. After hanging up, Assia returned to the lounge, but Else Ludwig, her German au pair, sensed nothing unusual.

It was a cloudy, dry, cold day, just four degrees Celsius and they all three Assia, her daughter Shura, and Else stayed indoors. Else had asked for permission to visit her friend Olga, who lived a short walking distance away and, at 7.30 p.m., before leaving, she went into the four-year-old Shuras room, and saw that she was in her bed, and asleep. Mr Wevill was in her bedroom. She was still dressed.

Assia then acted quickly. She made sure that the sash-type window in the kitchen was fully shut and pushed the small dining table and chairs over to the wall. From her bedroom she fetched some sheets, pillows and an eiderdown, and laid them on the kitchen floor, next to the gas oven. She poured herself a tot of whisky that she kept for occasional guests she had abstained from alcohol throughout her life and gulped it down. With another tot she then swallowed some sleeping pills. Seven times she gulped the whisky and swallowed the pills. Wobbling, she went into Shuras bedroom and lifted the sleeping child tenderly in her arms. In the dimly lit corridor she carefully negotiated the two steps that led back down into the kitchen. She laid Shura on the makeshift bed, closed the kitchen door tightly, turned all the gas taps fully on and opened the door of the Mayflower gas cooker. She switched off the kitchen light. Then she lay down quietly beside her daughter, so as not to wake her up. Their heads were lying close to the gas cooker. Assias feet almost touched the door.

Next page