Copyright 2011 by Eilat Negev and Yehuda Koren

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Bantam Books,

an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

B ANTAM B OOKS and the rooster colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain by JR Books, London, in 2011.

Excerpts from The Old Century and Seven More Years and various

other letters and archival material, copyright by Siegfried Sassoon.

Used by permission of the Estate of George Sassoon.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Negev, Eilat.

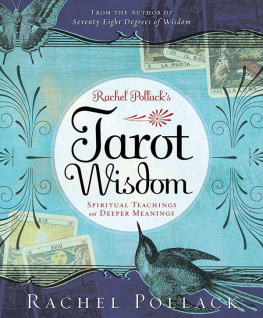

The first lady of Fleet Street : the life of Rachel Beer: crusading heiress

and newspaper pioneer / Eilat Negev and Yehuda Koren.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-345-53238-1

1. Beer, Rachel, 18581927. 2. Newspaper editorsGreat BritainBiography. 3. Women newspaper editorsGreat BritainBiography. 4. Newspaper publishingGreat BritainHistory. 5. Women publishersGreat BritainBiography. 6. Observer (London, England) 7. Sunday times (London, England : 1822) I. Koren, Yehuda.

II. Title.

PN5123.B345N46 2011

070.5092dc23

[B] 2011017498

www.bantamdell.com

Jacket design: Christine Kell

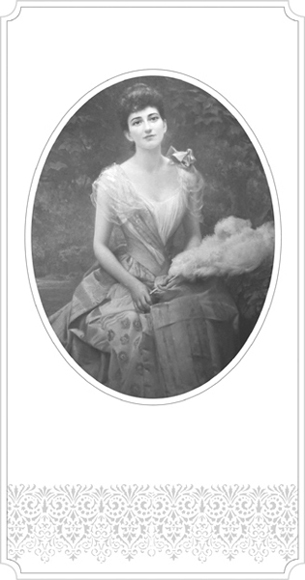

Jacket photograph: National Portrait Gallery, London

v3.1

Contents

Prologue

Late May 1903. Earls Court, a two-story

stone mansion in Tunbridge Wells.

A slight woman sits erect in her chair, nearly swallowed by her weighty crepe mourning dress. Heavily framed mirrors, priceless paintings, dim-gilt Chinese cabinets, and fresh lilies and orchids adorn every inch of the spacious drawing room.

She is almost numb in the presence of the seventy-three-year-old barrister sitting opposite her. Though he is a Master in Lunacy, summoned by the court to certify her mental state, Thomas H. Fisher is not a physician, and has not been schooled in psychiatry. This womans fate lies in his handsif he signs a document certifying that she is of unsound mind, she will be stripped of many of her rights, wont control the considerable inheritance due to her from her wealthy husband, and will be consigned to the outside government of herself, her manors, messuages, lands, goods and chattels.

That he is there is not surprising. Three physicians have already examined this woman and filed their reports, all at the request of her own family. One of them, Dr. George Henry Savage, is a leading expert in the field of lunacy. Though in his book On Soundness of Mind and Insanity, published that very year, Dr. Savage admitted that what is sane in one man is insane in the conduct of another, and what may be sane at one period of our lives would be insane at another, his assessment of this woman allowed for no such ambiguity. He pronounced her of unsound mind after one short interview.

Still, she might have filed legal documents. She could have tried to refute the judgments on her sanity. She has not, and she will not. She sits passively, instead, sensing that these matters are a fait accomplithe verdict has already been reached, and the forces allied against her are too strong to be defeated.

ONE MIGHT ASSUME that Rachel Beer, the woman in question, was just another pampered English lady, either too proud or too ill-prepared by a life in which her every need was met by others to do anything but surrender meekly to outside judgments. In truth, she was anything but that stereotypical Victorian lady. She achieved a more stunning kind of success than can be measured in bank accounts or stock portfolios.

In the late nineteenth century, women were denied the vote and were not given equal access to education. It was actually believed that too much intellectual activity would cause them nervous breakdowns. It was at this time that Rachel Beer owned and edited the Sunday Times and, eventually, The Observer. She was the first and only woman to edit two national newspapers, over eighty years before another woman was to take the helm of a Fleet Street paper. When one considers that many of her women contemporaries hardly had access to a newspaper, her accomplishments are all the more remarkable.

The few women who managed to crack the leaded glass ceiling in journalism and in most other careers in Rachel Beers time provoked extreme antagonism, and their assertiveness was perceived as a threat. Female journalists were often restricted to the so-called Womens Sphere, reporting on the latest frocks, frills and society gossip. Politics were considered out of bounds for them, and they werent welcome in the Press Gallery of the House of Commons. Though she was deprived of the tips and connections to which male journalists had ready access, Rachel Beer adamantly refused to limit herself to feminine topics. She fearlessly raised her voice on foreign and domestic matters throughout her time at both the Sunday Times and The Observer.

As an editor, Rachel Beer championed causes like the Public Amusements Bill, an innovative means of reducing crime and reforming morals through ratepayer-funded free educational and entertainment functions for the lower and middle classes. A working woman herself, she also stood for various womens causes. At the Womens International Congress, she made a memorable statement: It was Victor Hugo who said that the nineteenth century is the womans century. At the root of the whole question lies the demand for the rightno, not to votebut to labour, and to receive adequate pay for work done. She even took on traditional male bastions, calling for the resignation of the commander-in-chief and the elimination of his wasteful and expensive position.

She and her husband, Frederick Beer, who inherited The Observer from his father, were leading London socialitesexhibitions, musical soires, and theater and opera performances were held at their opulent Mayfair mansion, and they were frequently featured in the society pages. Their collection of paintings was coveted by museums, andas Rachel was a gifted pianist and composerthey also owned a wide array of the finest musical instruments. But though the Beers were fortunate enough to have been born into wealth, and didnt deny themselves luxuries, they clearly understood the obligations that came with that privilege. Their philanthropic efforts were impressive in their breadth and the level of their generosity.

Rachel was evidently a woman in love with life, the possessor of a vigorous and adventurous soul. Why, then, at forty-five, did she submit so passively to those questioning her sanity and her ability to care for herself? Why did she allow herself to be torn from her active life and her prestigious position in society?

In seeking answers to these questions, we must look not only at Rachels astounding life and career but at the meteoric rise to riches of two prominent Jewish immigrant families. Rachel Beer (ne Sassoon) was the daughter of S. D. Sassoon, the grandson of the familys patriarch, Sheikh Sason ben Saleh. The Sassoons ascent to power and wealth spread their considerable influence from Baghdad to Bombay and beyond, eventually leading them to prominence in London, the great commercial center of the world. Her husbands family had its roots in the harsh Frankfurt ghetto. His father, Julius Beer, relocated to London and made his fortune through investing in the emerging technologies of the timerailroads and submarine telegraphy. When Rachel and Frederick married, they united the wealth and histories of their grand families.