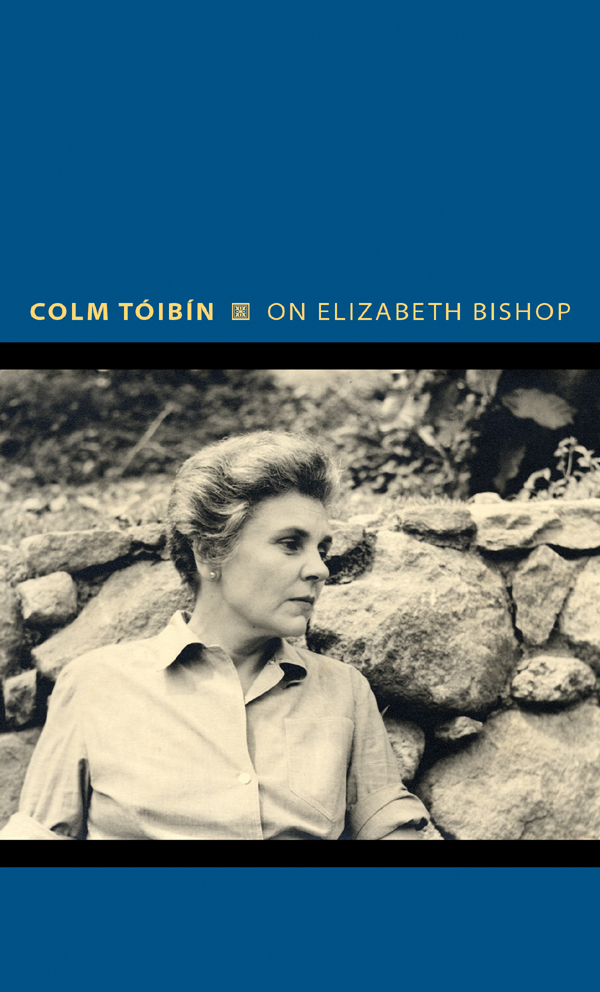

ON ELIZABETH BISHOP

ON ELIZABETH BISHOP

WRITERS ON WRITERS

Philip Lopate | Notes on Sontag

C. K. Williams | On Whitman

Michael Dirda | On Conan Doyle

Alexander McCall Smith | What W. H. Auden Can Do for You

Colm Tibn | On Elizabeth Bishop

COLM TIBN  ON ELIZABETH BISHOP

ON ELIZABETH BISHOP

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2015 by Colm Tibn

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Owing to limitations of space, all acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published material can be found on page 207.

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket photograph Bettman/CORBIS. Courtesy of Vassar College Archives and Special Collections.

Cover photograph courtesy of Vassar College Archives and Special Collections.

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-15411-4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014951285

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Minion Pro and Myriad Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Hedi El Kholti

For Hedi El Kholti

CONTENTS

CONTENTS

ON ELIZABETH BISHOP

ON ELIZABETH BISHOP

No Detail Too Small

She began with the idea that little is known and that much is puzzling. The effort, then, to make a true statement in poetryto claim that something is something, or does somethingrequired a hushed, solitary concentration. A true statement for her carried with it, buried in its rhythm, considerable degrees of irony because it was oddly futile; it was either too simple or too loaded to mean a great deal. It did not do anything much, other than distract or briefly please the reader. Nonetheless, it was essential for Elizabeth Bishop that the words in a statement be precise and exact. Since we do float on an unknown sea, she wrote to Robert Lowell, I think we should examine the other floating things that come our way carefully; who knows what might depend on it? In her poem The Sandpiper, the bird, a version of the poet herself, was a student of Blake, who celebrated seeing a World in a Grain of Sand / And a Heaven in a Wild Flower.

A word was a tentative form of control. Grammar was an enactment of how things stood. But nothing was stable, so words and their structures could lift and have resonance, could move out, take in essences as a sponge soaks in water. Thus language became gesture in spite of itself; it was rooted in simple description, and then it bloomed or withered; it was suggestive, had a funny shape, or some flourishes, or a tone and texture that had odd delights, but it had all sorts of limits and failures. If words were a cry for help, the calm space around them offered a resigned helplessness.

In certain societies, including rural Nova Scotia where Bishop spent much of her childhood, and in the southeast of Ireland where I am from, language was also a way to restrain experience, take it down to a level where it might stay. Language was neither ornament nor exaltation; it was firm and austere in its purpose. Our time on the earth did not give us cause or need to say anything more than was necessary; language was thus a form of calm, modest knowledge or maybe even evasion. The poetry and the novels and stories written in the light of this knowledge or this evasion, or in their shadow, had to be led by clarity, by precise description, by briskness of feeling, by no open displays of anything, least of all easy feeling; the tone implied an acceptance of what was known. The music or the power was in what was often left out. The smallest word, or the holding of breath, could have a fierce, stony power.

Writing, for Bishop, was not self-expression, but there was a self somewhere, and it was insistent in its presence yet tactful and watchful. Bishops writing bore the marks, many of them deliberate, of much re-writing, of things that had been said, but had now been erased, or moved into the shadows. Things measured and found too simple and obvious, or too loose in their emotional contours, or too philosophical, were removed. Words not true enough were cut away. What remained was then of value, but mildly so; it was as much as could be said, given the constraints. This great modesty was also, in its way, a restrained but serious ambition. Bishop merely seemed to keep her sights low; in her fastidious version of things, she had a sly system for making sure that nothing was beyond her range.

Bishop was never sure. In the last line of her poem The Unbeliever, she has her protagonist state that the sea wants to destroy us all, but the last line of Filling Station will read: Somebody loves us all. In the poetics of her uncertainty surrounding the strange business of us all, there was something hurt and solitary. In the first poem in her first book, a poem called The Map, it was as though the world itself had to be studied as a recent invention or something that would soon fade and might need to be remembered as precisely as possible by a single eye.

For her, the most difficult thing to do was to make a statement; around these statements in her poems she created a hard-won aura, a strange sad acceptance that this statement was all that could be said. Or maybe there was something more, but it had escaped her. This space between what there was and what could be made certain or held fast often made her tone playful, in the same way as a feather applied gently to the inner nostril makes you sneeze in a way that is amused as much as pained.

In an early essay on Gerard Manley Hopkins, Bishop wrote about motion in poetry: the releasing, checking, timing, and repeating of the movement of the mind according to ordered systems. Hopkins, she wrote, has chosen to stop his poems, set them to paper, at the point in their development where they are still incomplete, still close to the first kernel of truth or apprehension which gave rise to them. Thus the idea of statement in Hopkins, the bare sense of a fact set down, offers a revelation oddly immediate and sharp, true because the illusion needs to be created that nothing else was true at the time the poem was written. And that making a statement has the same tonal effect as recovering from a shock, recovering merely for the time necessary to say one thing, including something casual and odd, and to leave much else unsaid.

Thus a line in a poem is all that can be stated; it is surrounded by silence as sculpture is by space. Hopkins could begin a poem: I wake and feel the fell of dark not day. Or No worst, there is none. Or Summer ends now. Only then, once the bare statement had been madesomething between a casual diary entry and something chiseled into truthcould the poem begin to be released and then controlled according to ordered systems.

Bishop would begin poems with lines such as I caught a tremendous fish or Here is a coast; here is a harbor or September rain falls on the house or Still dark or The sun is blazing and the sky is blue, and manage even in such inauspicious openings a tone that attended to the truth of things, a tone also of mild, distracted, solitary unease in the face of such truth.

Next page

ON ELIZABETH BISHOP

ON ELIZABETH BISHOP