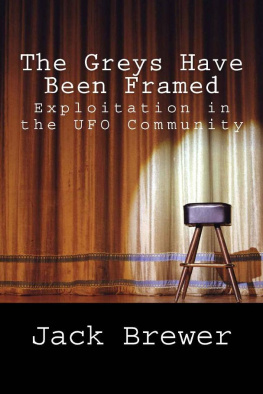

Zane Greys Wild West

A Study of 31 Novels

Victor Carl Friesen

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina, and London

A version of Chapter 1 appeared originally in Zane Grey Review 16, no. 4 (June 2001); Chapter 8 appeared in Zane Grey Review, 25, no. 1 (May 2010); Chapter 14 appeared in Zane Grey Review 25, no. 3 and 4 (December 2010); a version of Chapter 18 appeared in Zane Grey Review 16, no. 1 (December 2000); and a version of Chapter 25 appeared in Zane Grey Review 24, no. 4 (December 2009). Chapter 15 was originally published in The Concord Saunterer, New Series 6 (1998), and appears here courtesy the Thoreau Society Collections at the Thoreau Institute at Walden Woods.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1273-7

2014 Victor Carl Friesen. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Cover art: Charles Marion Russell, A bad hoss, 1905 color lithograph from original 1904 painting (Library of Congress)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To my fellow members of Zane Greys West Society

Preface

There is some difficulty in selecting 31 of Zane Greys Westerns, half his total output, for inclusion in a book of literary discussion. Of course, a volume with continuing popularity has to be included. I am thinking now of Riders of the Purple Sage, the best-selling Western ever written (and its sequel, The Rainbow Trail). But once one gets beyond a dozen or so obvious choices, gradations in literary worth become more debatable. Different critics will disagree as to which plots are better written; what seems overdramatized to one may not be distracting to others if the characters are sufficiently gripping. Also, personal taste becomes a factor, where subject or locale and memories connected with first readings play a part (see Pfeiffer, So You Want..., 2, in the bibliography; page references other than to Greys novels pertain to this bibliography). My choices stem from wishing to best show the scope of Greys interests in the West and his powerful descriptions of the land. How does he convey the ideals of this opening territoryhis stated aim?

My selection of novels provides as wide a sampling as possible, a range of subjects encompassing frontiersmen, horse wranglers, cowmen, gunmen, prospectors, bandits, Native Americans, backwoodsmen, hunters, fishermen, foresters, farmers, teachers, and construction workers (on railroad and telegraph lines). The work of all these people is predominantly outdoors, with wild nature as setting, a determinant of action and often of character too, particularly effective as desert in Wanderer of the Wasteland or deep woods in The Man of the Forest. Besides these locales parklands, canyons, mountains, rivers, lakes, and an ocean are the backdrops in some fifteen statesfrom West Virginia in the East (the first western frontier) to Arizona in the Far West, the setting for nearly half the novels (it is Greys favorite state), and even beyond to California.

The time of the 31 books dates from events leading to the last battle of the Revolutionary War, at Fort Henry on the Ohio River, 1782 (Betty Zane), to the flapper era of the 1920s (Code of the West). A cluster of books deals with the cowboy world that developed in the western states or territories following the Civil War, the late 1860s through to the 1880s. It was the cow pony that raised the rider above the rest of us earthbound beings and made him a folk hero. Grey builds up this fact in such books as the spirited Knights of the Range. And gunmen-cowboys can be heroic too, as in Robbers Roost and Nevada, the latter at the turn of the century. In Last of the Duanes, the title character is in fact the ultimate gunslinger. (Heroes with the lesser role of shoot-out artist appear in at least half a dozen other books considered here, Lassiter in Riders being an obvious example.)

Another cluster of books pertains to World War I. The Desert of Wheat graphically describes battle scenes and a soldiers subsequent convalescence. The Call of the Canyon, a fine sociological study, and The Shepherd of Guadaloupe show returned veterans trying to adjust to an uncaring Roaring Twenties society (in Shepherd, the quick-witted jibes of a secondary female character pretty much steal the show). Grey sees some hope of veterans finding themselves in the elemental West, its simpler, richer lifestyle, rather than in the East (that man is richest whose pleasures are the cheapest, affirms naturalist Henry David Thoreau [Journal 8:205]). Sometimes, as well, we see an Easterner, man or woman, a newcomer to the spacious West, find his or her real home and vocation under The Light of Western Stars (in this book a New York woman, a socialite, successfully runs a ranch). While a characters real battle may seem to be for mere survival and/or material success, it is really for inner fulfillment.

Several novels have women as main protagonists, like The Call of the Canyon above. In Woman of the Frontier Greys understanding portrayal of the title character makes it one of his best books. Under the Tonto Rim, another example, pictures a teacher in a hillbilly setting. The women are drawn from real life, people Grey knew (Wheeler, Two Roads..., 8; see also Pauly, 11420). He presents such a variety, in principal or supporting roles, all uniquely characterized, that on the whole they seem more interesting than the men, who are generally involved in physical action. This is the case in Wild Horse Mesa, where three women are portrayed, playing off each other to reveal their individualities, while a commenting hero looks on. Greys sure ear for dialogue between women or men (or between both) is key to his vivid delineation of these people.

I have included most books focusing on horsesForlorn River is one, Wildfire a particular favorite. Grey knows and loves these animals, and depicts them well. Also, there is a good proportion of novels of direct historical interest, The U. P. Trail being an example, where East meets West through railroad building in the 1860s. Cattle drives, extending through several states/territories from 1867 to 1882 before more railroads ended their necessity, are picturesquely captured in The Trail Driver. And the near extermination of buffalo in Texas, 1874, is accurately told in The Thundering Herd. Gold-rush fever is described in The Border Legion (Montana, 1863) and Thunder Mountain (Idaho, 1906). As well, I have included Zane Greys very first novel, self-published Betty Zane (1903); the last published in his lifetime (and written in the first person), Western Union (1939); and one recently published in book form, the previously mentioned Last of the Duanes (1996).

The inclusion of two other books, generally not considered among Greys best, needs some explanation. Another war-veteran account, Rogue River Feud, is hardly a Western, as the term is commonly defined, for its overall subject is fishingcommercial and sport. However, the setting is certainly as far westerly as one can be in the contiguous United States, down Oregons most scenic river to the Pacific coast, and there

Next page