The Tacky South

SOUTHERN LITERARY STUDIES

Scott Romine, Series Editor

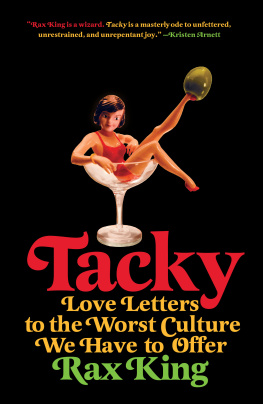

TheTACKY

SOUTH

Edited byKATHARINE A. BURNETT

& MONICA CAROL MILLER

Foreword byCHARLES REAGAN WILSON

LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS  BATON ROUGE

BATON ROUGE

Published by Louisiana State University Press lsupress.org

Copyright 2022 by Louisiana State University Press

All rights reserved. Except in the case of brief quotations used in articles or reviews, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any format or by any means without written permission of Louisiana State University Press.

Manufactured in the United States of America First printing

DESIGNER: Mandy McDonald Scallan

TYPEFACE: Livory

Cover illustration: Sahroe/Shutterstock.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Burnett, Katharine A., 1983 editor. | Miller, Monica Carol, 1974editor. | Wilson, Charles Reagan, writer of foreword.

Title: The tacky South / edited by Katharine A. Burnett, and Monica Carol Miller ; foreword by Charles Reagan Wilson.

Description: Baton Rouge : Louisiana State University Press, [2022] | Series: Southern literary studies | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021053985 (print) | LCCN 2021053986 (ebook) | ISBN 978-0-8071-7734-1 (cloth) | ISBN 978-0-8071-7789-1 (paperback) | ISBN 978-0-8071-7790-7 (pdf) | ISBN 978-0-8071-7791-4 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: TackinessSouthern States. | Southern StatesIn popular culture. | Southern StatesPublic opinion. | Southern StatesCivilization. | Parton, Dolly. | Aesthetics, American.

Classification: LCC F209 .T25 2022 (print) | LCC F209 (ebook) | DDC 306.0975dc23/eng/20220124

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021053985

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021053986

Contents

CHARLES REAGAN WILSON

KATHARINE A. BURNETT AND MONICA CAROL MILLER

JOLENE HUBBS

JOE T. CARSON

ELISABETH AIKEN

GARTH SABO

CATHERINE EGLEY WAGGONER

JIMMY DEAN SMITH

JILL E. ANDERSON

AARON DUPLANTIER

MONICA CAROL MILLER

JARROD HAYES

KATHARINE A. BURNETT

JOSEPH A. FARMER

MARSHALL NEEDLEMAN ARMINTOR

TRAVIS A. ROUNTREE

MICHAEL P. BIBLER

ANNA CREADICK

ISABEL DUARTE-GRAY

SUSANNAH YOUNG

Foreword

THE SOUTHERN TACKY HALL OF FAME

V. S. Naipaul was the most world-weary looking man I had ever seen when he visited my office at the Center for the Study of Southern Culture in 1984. He was touring the University of Mississippi campus as part of his time in the American South that led to A Turn in the South (1989), and that well-traveled writer looked bored. The Nobel Prize-winning authors eyes lit up, though, when he viewed a framed poster that portrayed Elvis Presley walking up to heaven. As Naipaul put it, the poster showed a tight-trousered, full-bottomed Presley playing a guitar in the lower left-hand corner, with a staircase leading up to his mother and Gracelandthe Presley house in Memphisin the sky. Country legend Hank Williams was there to greet him. Graceland was suspended in air, with surrealistic, eerie colors of bright reds and blues, and meteors flashed by. A crown decorated the canvas as well.

Naipaul was harsh in judging it as redneck fulfillmentsocially pathetic at one level, but he also saw it as religious art of a kind, with Christian borrowings that included the beatification of the central figure, with all his sexuality. Graceland seemed like a version of the New Jerusalem in a medieval doomsday painting. Throughout his book about the South, Naipaul saw the region as a postcolonial society and related it to the West Indies where he grew up. Emancipated slaves in the British West Indies at first had few heroes, he recalled, but then they embraced such cultural figures as sportsmen, then musicians, and then politicians. The glory of the black leader became the glory of his people, he concluded. Something of that adulation from the islands seemed to be at the back of the Presley cult. He realized that music in the South carried much of a peoples emotional needs.

Naipauls observations provide an appropriate preview to this book on southern tacky, a phenomenon that has been largely ignored by scholars but that offers insights into American studies and southern studies. The beginning place is history. When did this phenomenon begin? Did John Smith, the worldly adventurer, set souvenirs of his travels on his desk at Jamestown? Did Thomas Jefferson build an ingenious contraption to hold his collection of southern tacky at Monticello? Neither scenario is likely. I think of tacky artifacts as mass-produced ones that are part of popular culturecharacteristic of modern times and not earlier. William Gilmore Simms was apparently the first writer to evoke the term, noting in The Partisan (1835) a dirty-field-tackey. The term did not come into common usage, though, until the late nineteenth century. Century magazine (September 1888) referred to parts of Georgia with its po whites and pineywood tackeys. A Peterson magazine (January 1884) writer identified a Virginia countryman as a specimen of the genus tacky, and we can certainly be grateful for this unexpected biological grounding to the concept.

Material southern tacky dates back to the late nineteenth century, when admirers of Confederate leaders created an iconography of Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson, Jeb Stuart, and others, and placed their images on mass-produced prints, knives, whiskey bottles, sacks of flour, roadhouse signs, decks of cards, and innumerable other products of regional business. The southern identity a hundred years ago was a white-dominated, political-military regional self-consciousness, and the Confederate images symbolized it during the initial development of a broad popular culture in the region. In the twentieth century, the southern identity became more democratized. The redneck rebel soldier on a t-shirt seemed to interest the modern South more than the men staring down from Stone Mountain.

The images of southern tacky by the late twentieth century showed that the southern identity became tied in with popular culture more than ever. Likenesses of the heroes and celebrities of music, literature, film, and television are found on magazines, posters, postcards, buttons, pins, ties, shoestrings, and matchbox covers, to name only a few of the carriers of the iconography. Dolly Parton, Hank Williams, Jr., Richard Petty, Andy Griffith, the Dukes of Hazzard, Rhett and Scarlettall are members of the Southern Tacky Hall of Fame.

The King of southern tacky is surely Elvis. Born into a poor Mississippi family, Presley developed an aesthetic of bright colors, opulence, and sensuality that has much in common with the fantasies of other poor, rural, white southerners. With his fabulous success, he remained true throughout his life to this ideal of taste. Graceland seems to some visitors a nightmare of the garish, but it is filled with touches of vitality and good humor. His image, moreover, adorns countless artifacts because people will buy virtually anything with Elvis on it. Ten of thousands of snapshots were made of him, fan shots, and each angle of him in his jumpsuit is a token of southern tacky.

Southern tacky lacks the moral connotations of trashy when used to describe a southern poor (or nonpoor) white. But it has aesthetic connotations. Again, the poor white is the starting point for understanding. An 1889 reference indicated that tacky in the South included a man neglectful of personal appearance. The word is also used to describe a scruffy horse, which in the etymological imagination seems close to the image of the poor white.

Next page

BATON ROUGE

BATON ROUGE