Sounds True

Boulder, CO 80306

2012, 2016 Joseph M. Marshall III

SOUNDS TRUE is a trademark of Sounds True, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the author and publisher.

Published 2012, 2016

Cover and book design by Rachael Murray

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-1-62203-996-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Marshall, Joseph, 1945

The Lakota way of strength and courage : lessons in resilience from the bow and arrow / Joseph M. Marshall III.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-60407-878-7

1. Teton IndiansHistory. 2. Teton philosophy. 3. Teton IndiansSocial life and customs. I. Title.

E99.T34.M36 2012

978.004975244dc23

2011028292

eBook ISBN 978-1-60407-747-6

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

OTHER BOOKS BY JOSEPH M. MARSHALL III

Nonfiction

Returning to the Lakota Way: Ancient Values for the Modern World (2012)

To You We Shall Return: Lessons About Our Planet from the Lakota

The Power of Four: Leadership Lesson of Crazy Horse

Keep Going: The Art of Perseverance

The Day the World Ended at Little Bighorn: A Lakota History

Walking with Grandfather: The Wisdom of Lakota Elders

The Journey of Crazy Horse: A Lakota History

The Lakota Way: Stories and Lessons for Living

The Dance House: Stories from Rosebud

On Behalf of the Wolf and the First Peoples

Fiction

The Long Knives Are Crying

Hundred in the Hand

Winter of the Holy Iron

How Not to Catch Fish: And Other Adventures of Iktomi (childrens)

Audio

To You We Shall Return: Lessons About Our Planet from the Lakota

Quiet Thunder: The Wisdom of Crazy Horse

Stories from the Lakota Way

For Connie

Introduction

Child of the Moon, Child of the Sun

There was a time when Lakota boys looked at a new bow and arrows the way any modern teenager gazes at an iPod, a cell phone, or the latest version of a video gamelongingly and lovingly. There was one basic difference, however. Lakota boys eventually learned how to make their own bows and arrows and learned the life lessons associated with them.

Bows and arrows have been around for thousands of years and, as weapons for hunting and warfare, were critical to the survival of cultures all over the world. They were frequently and literally the difference between starvation and plenty and very often between life and death.

Although I heard about the bow (itazipa) and the arrow (wahinkpe) in stories told by both of my maternal grandparents, I never actually saw the real thing until my grandfather made a set in 1950. The bow was of ash wood, and the arrows were thin chokecherry stalks. Like countless Lakota boys before me, I was immediately drawn to them. The feeling was somewhat like meeting an old friend. More than likely, I felt an inherent cultural connection with them. My lifelong fascination began the moment my grandfather placed the arrows, one at a time, on the bowstring and shot them into the air. As I watched those feathered shafts arc gracefully through the sky, I knew they would be part of my life for as long as I lived.

When I asked where the bow came from, it was my grandmother who replied.

From the moon, she said.

She explained that the moon was a woman, and it was she who gave us Lakota the bow. I accepted what she said without question. Several evenings later, she showed me the sliver of a new moon hanging in the sky. The thin, silver crescent looked exactly like my grandfathers bow when he drew it back to shoot an arrow.

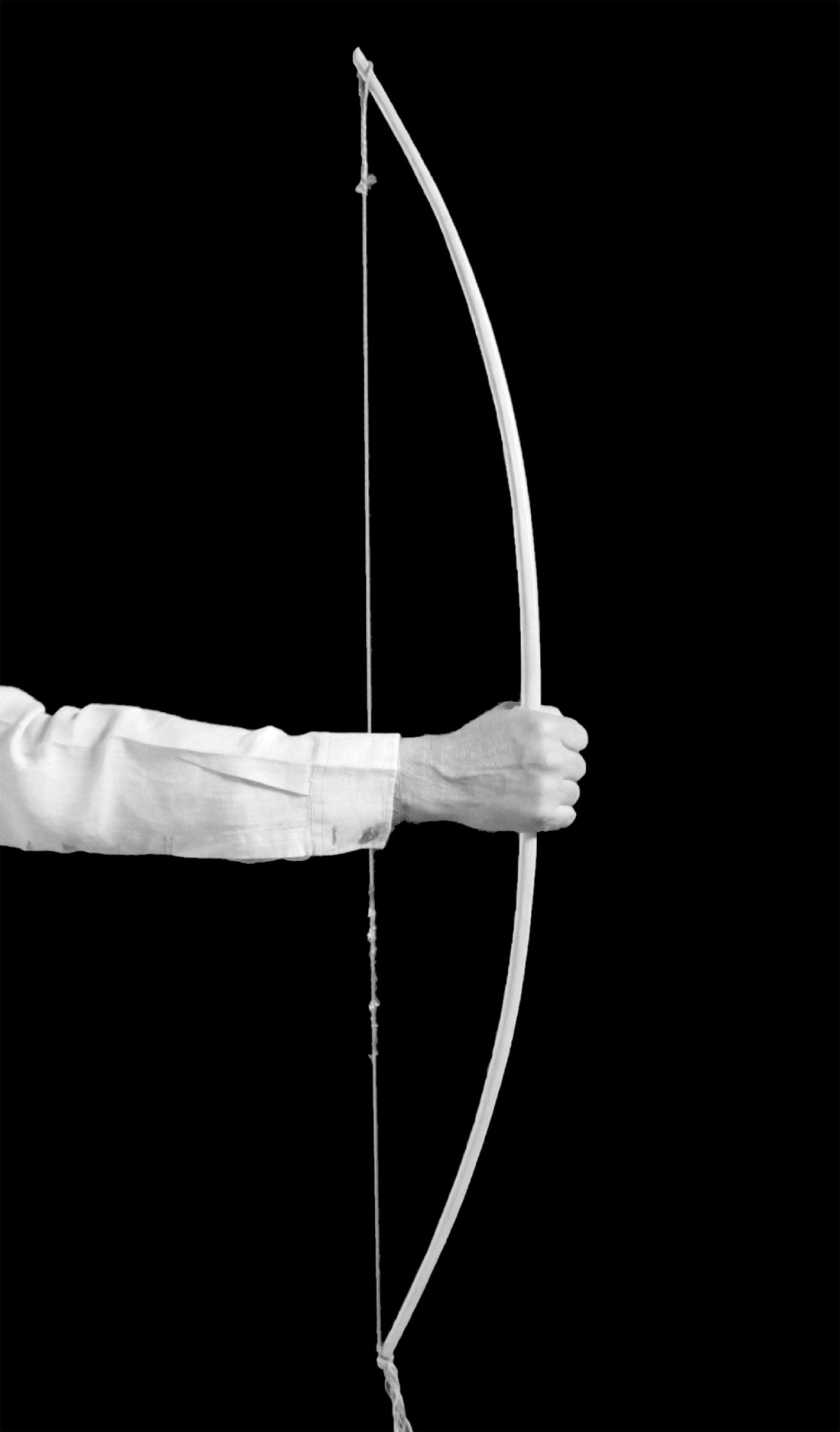

According to my grandfather, someone in the distant past saw that same sliver of a new moon and related it to the function of a bow. A bow works by reacting to being drawn, or bent, when the archer pulls back on the string. When the string is released, the reflexive action launches the arrow. Anyone who is familiar with how a bow works, and especially anyone who has constructed primitive bows, knows that the bow must be designed to withstand the stress of being drawn or bent. Bad design or poor craftsmanship will cause one or both of the limbs to work improperly or even break under stress.

If nothing else, a primitive Lakota bow is the epitome of simplicity. When strungthat is, when the string is attached to both tipsit resembles a narrow capital D. It is widest in the middle, the point where the archer holds it. The length from below this handle to the tip is the bottom limb, or wing. Above the handle is the top limb. In order for the bow to function smoothly time after time, both limbs have to bend uniformly. In other words, the stress has to be equal on both limbs.

The thinnest sliver of a new moon also is widest in the middle and gradually tapers to both ends. As my grandfather said, some archer in the distant past realized that he (or she) was looking at a design wherein the limbs of a bow would flex, or bend, evenly. Therefore, practically, as well as spiritually, the moon did give us the bow.

Lakota ashwood bow with sinew string

Sooner or later, I asked the next obvious question: if the bow came from the moon, where did the arrow come from?

From the sun, was my grandfathers reply.

I already knew that the sun was considered a man, so I deducedcorrectly, as it turned outthat the arrow must be male. One late afternoon, when the suns rays were shafts of light descending through a broken bank of clouds, my grandfather pointed to them. Those were the arrows of the sun. While the bow was a graceful curve, the arrow was absolutely as straight as straight could be.

Neither the moon nor the sun told us what sort of material the bow and arrow were to be made of. However, given that my Lakota ancestors harvested from the natural environment everything they used, wore, lived in, and ate, they knew the characteristics of every kind of raw material. Hardwoods were used for bows because they were more flexible than softwoods, and both soft-and hardwood stalks were used for arrows.

In pre-reservation days, bows and arrows were absolute necessities for the Lakota hunter/warrior. He used that weapon set to procure the resources needed for food, shelter, and clothing, as well as to defend family, home, and community against enemies. Around the age of twelve, every boy began to learn to craft them. It was a skill refined and polished year after year. There were usually a few who were much more skilled than others. Nevertheless, every man in the village was a bow maker and arrow smith.

During the first years on the reservations, bows and arrows were still being made and used for hunting. Some were made to sell to whites, and several white collectors had been able to acquire some prior to the reservation era. There were still many men of my grandparents generation, like my grandfather, who had the knowledge and skills to make bows and arrows. My father had a basic knowledge, but as far as I know, he never made or used them. Technically speaking, the Lakota primitive bow and arrow have not been lost to history, but they have only barely survived.

Next page