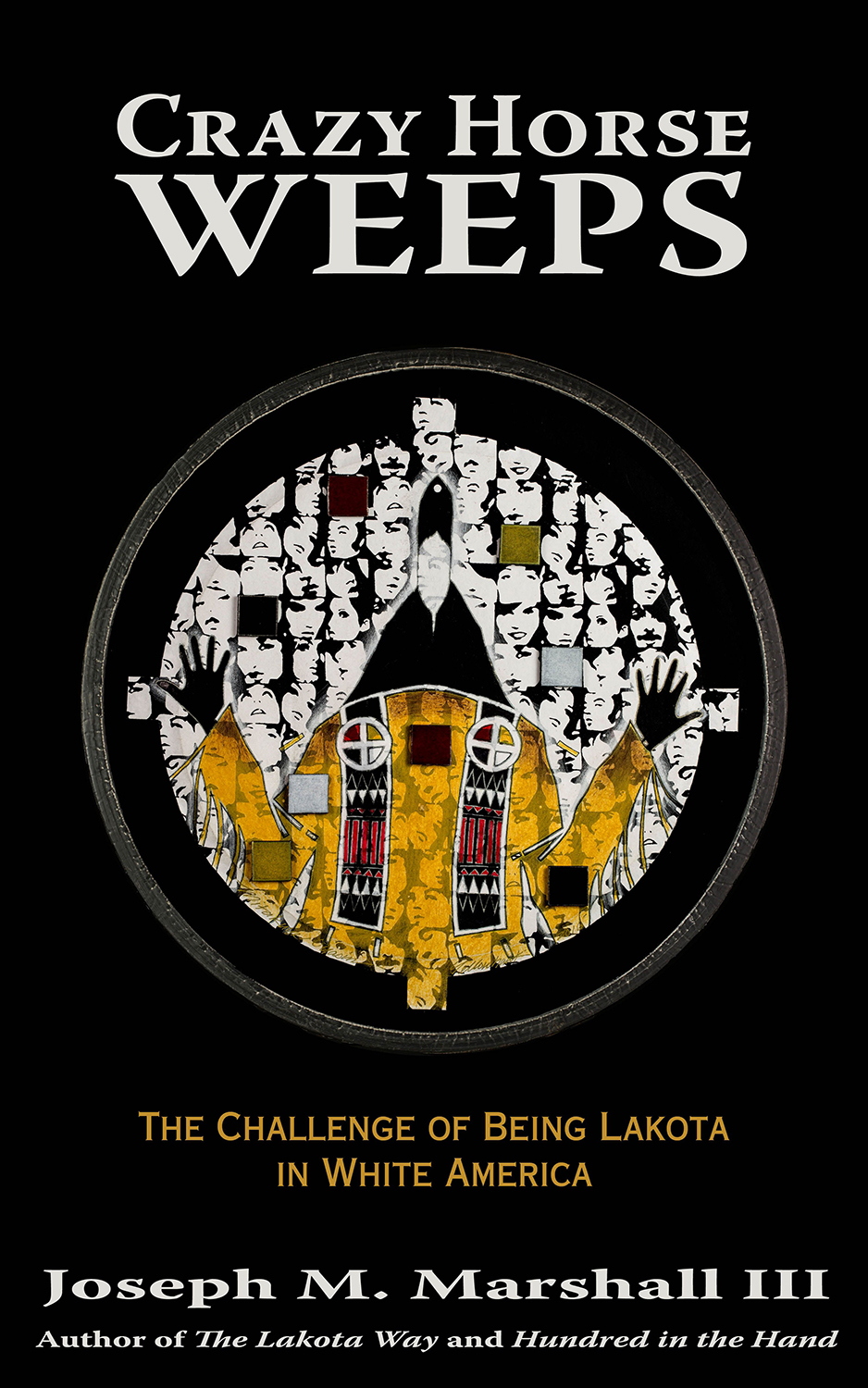

Joseph M. Marshall III

Author of The Lakota Way and

Hundred in the Hand

Preface

One of the most heartbreaking stories I ever heard about Crazy Horse had nothing to do with battles or warfare. I could feel the tears welling up in my eyes when I heard how he wept at the burial scaffold of his daughter who had died of cholera. It became more meaningful, and more heartbreaking when I became a parent.

His heart was broken by the very tragedy that most of us fear more than deaththe loss of a child. Though it is a lonely experience to the parents who have suffered this tragedy, the loss he and his wife endured was obviously not the first for Native parents at that point in our history. And it would not be the last. Furthermore, there is an added factor that even astute historians tend to overlook.

For Crazy Horse and his wife, Black Shawl, there was one unfortunate commonality with other Native parents who lost children in that era. The suffering and deaths of their beloved children (and many adults as well) was directly attributable to invading nonindigenous newcomers. I am, of course, referring to white people, the Europeans and then the Euro-Americans. The daughter of Crazy Horse and Black Shawl was afflicted with cholera, a disease unknown to the indigenous people of North America until the arrival of Europeans, and one for which the prior inhabitants of this continent had no immunity. Other diseases for which Native people had no immunity were measles, chicken pox, and smallpox. The latter, of course, was the most devastating for our ancestors.

In the broader context, had white people not come to North America, Crazy Horse and Black Shawls daughter, whom they had named They Are Afraid of Her, would not have contracted cholera and would likely have lived a long life. But the horrific reality is that the Europeans did come and the Euro-Americans continued the invasion. The stage was set for Crazy Horses daughter hundreds of years before she was born. If the Lakota had avoided contact with the invaders, perhaps the impact of diseases would have been less. But diseases were not the only consequence.

Difficult, sudden, unexpected, and even tragic change had fallen upon Crazy Horses people long before the death of his daughter. Furthermore, this had been occurring for the indigenous people of Turtle Island (more or less the common pre-European name for North America among many indigenous nations) for at least three hundred years by then, attributable to the newcomers from Europe. It is difficult, perhaps impossible, to point to a particular moment and determine that as the point in time when change began to manifest negatively for indigenous people as a consequence of the newcomers arrival.

Negative changes included displacement from villages, homelands, and hunting lands; confusing and convoluted interactions with the newcomers; untold numbers of deaths from unknown diseases; confrontations; battles; massacres; and in the end, long, drawn-out wars; broken promises; loss of lands; limited existence on reservations; and loss of culture. Of course, these rather antiseptic descriptions cannot fully describe the number and horrific nature of atrocities suffered by indigenous people at the hands of white people. There are too many, but a very short list includes the New England smallpox blankets, Trail of Tears, the Long Walk suffered by the Navajo, Sand Creek, and Wounded Knee.

A realistic description of each would be nearly impossible for most people to read. One example is the Sand Creek Massacre. It occurred in November of 1864, in which the 3rd Colorado Volunteers under the command of Colonel John Chivington (a Methodist minister) attacked a Cheyenne and Arapaho village encamped under a white flag at Sand Creek in eastern Colorado. Days later the attackers paraded through the streets of Denver with body parts of women and children attached to their uniforms. Of course, one can only imagine how those body parts became body parts. Multiply this kind of gut-wrenching ugly reality by a few hundred, and perhaps the average non-Native American can dare to try to understand the real history of North America in the past five hundred years.

Only now are white people, albeit still not enough, beginning to accept the extent to which their conquest of North America decimated the indigenous peoples who had already been here for tens of thousands of years. Regrettably and tragically, there is not a point at which it stopped completely. Granted, the physical atrocities have been fewer, but they are still occurring. And we must say that because of Wounded Knee in 1973, and because the killing of Native peoples by police continues to occur at the highest rate for any ethnic group, and because of the use of military tactics and equipment by police against the peaceful protests that began in 2016 against the oil pipeline in North Dakota. But the frightening reality is that the attitudes that enabled Manifest Destiny are still alive and are the basis for racism and government policies and actions.

Those attitudes fostered the US governments policies and actions that can be summed up in the phrase, Kill the Indian and save the man, the banner under which the assimilation of Native peoples into American mainstream society occurred. The consequences of those attitudes and policies have been the continued diminishing of Native languages and culture, which bears a further consequence that most of us Native peoples do not see or want to seethe assimilation into white mainstream culture. Furthermore, there is a darker and even more damaging consequencea skewed awareness of our own history, influenced heavily by white perspective.

We Lakota, and all indigenous descendants of the original Turtle Islanders, have endured much, to say the least, as previous paragraphs testify. We have lost much as wellinitially homelands and territories, freedom, and ancient lifestyles. Yet we are on the cusp of losing more. Indeed we stand on the edge of losing it all. The fact of the matter is our final stronghold is not territory or a piece of land. Our final stronghold is our sense of identity.

Identity is simply defined as the fact of being who or what a person or thing is .

Our Lakota identity was strong and powerful. For countless generations we were hunter-gatherers and evolved into a cohesive and well-defined society with strong and necessary roles for males and females, a society that formed beliefs, customs, traditions, spirituality, and values based on the realities of a relationship with the natural environment. We understood our roles and our place within the reality of the natural order. We looked on the land as a relative and not a commodity. In short, we knew who we were and where we had come from. However, that began to change the moment the newcomers from Europe gained a foothold into our territories and a semblance of credence in our thinking.

Our Lakota identity is obviously not what it once was. It has been altered by two broad and insidious factors: intermarriage with Europeans and Euro-Americans and forced assimilation into the mainstream American culture. Intermarriage thinned our bloodlines and was a factor in the alarming swiftness by which assimilation was able to diminish our sense of who we were, and who we are.

A necessary, if not frightening question that each of us contemporary Lakota must ask ourselves is a simple one, though I fear that while the answer may be simply given, the consequences of it are anything but simple: What language do we speak predominantly?