THE WILD WEST FOR KIDS

CRAZY HORSE

THE WILD WEST FOR KIDS

CRAZY HORSE

JON STERNGASS

Copyright 2014 by Jon Sterngass

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Sky Pony Press books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Sky Pony Press, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Sky Pony is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyponypress.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

eISBN: 978-1-62873-849-0

Manufactured in China, August 2013

This product conforms to CPSIA 2008

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sterngass, Jon.

Crazy Horse / Jon Sterngass.

pages cm. -- (The Wild West for kids)

Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-62636-159-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Crazy Horse, approximately 1842-1877--Juvenile literature. 2. Oglala Indians--Kings and rulers--Biography--Juvenile literature. 3. Indians of North America--Great Plains--Wars--Juvenile literature. I. Title.

E99.O3C729435 2014

978.0049752--dc23

[B]

2013033651

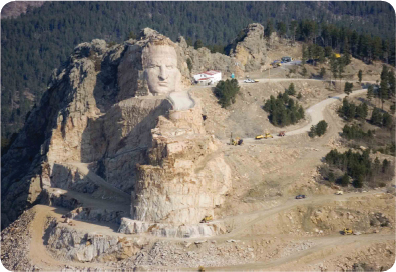

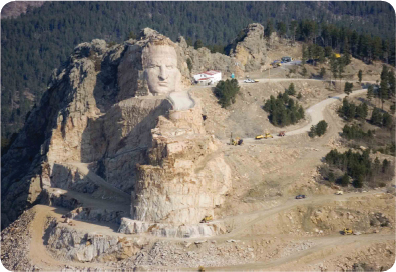

THE MYSTERIOUS WARRIOR

D eep in the heart of the Black Hills of South Dakota, the Crazy Horse Memorial rises out of Thunderhead Mountain. Under construction since 1948, it is a dramatic monument in the form of Crazy Horse, a Lakota Sioux warrior, riding a horse and pointing into the distance. If completed, the sculptures final dimensions will be 641 feet (195 meters) wide and 563 feet (172 m) high, making it the worlds largest statue. The memorial to Crazy Horse will dwarf one of the most popular monuments in the country, Mount Rushmore, located only eight miles (12 km) away. The heads of the presidents at Mount Rushmore are each 60 feet (18 m) high, but the head of Crazy Horse will be 87 feet (26.5 m) high.

Some wonder, however, if it will ever be finished. The carving was inspired by a letter to sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski, who had worked for a short time on Mount Rushmore. In 1939, Chief Henry Standing Bear wrote to Ziolkowski, My fellow chiefs and I would like the white man to know that the red man has great heroes, too. Ziolkowski began carving in 1948, and the work has been going on ever since. Ziolkowski died in 1982, but his wife and several children remain closely involved with the work. Although the face of Crazy Horse was completed and dedicated in 1998, the entire work is far from completion.

The Crazy Horse Memorial, located in the Black Hills of South Dakota, is being carved out of Thunderhead Mountain. It has been under construction since 1948. If finished, it will be the worlds largest sculpture.

Yet the monument to Crazy Horse is not without its critics, many of them Lakota. It is being carved out of land considered sacred by some Native Americans. Lame Deer, a Lakota medicine man, remarked, The whole idea of making a beautiful wild mountain into a statue of him is a pollution of the landscape. It is against the spirit of Crazy Horse. Russell Means, a famous Native American activist, also criticized the creation of the sculpture. Crazy Horses story continues to relegate us as a people to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, said Means. People think Indian people are relics; we do not exist in the present. That makes it easy for non-Indians to say, Oh, lo, the poor Indian, and we love his romantic image, and we are sorry for what our ancestors did to him, but we can continue to do it to these Indian people today with impunity.

So even in death, Crazy Horse continues to inspire people and excite argument. Who was this Lakota warrior and why does he still capture the imagination of twenty-first-century America.

A Mysterious Warrior

Crazy Horse is one of the greatest of Native American heroes, but much about his life is a mystery. It is not easy to write his biography. Crazy Horse was quiet and shy. He rarely spoke in public or participated in public ceremonies. He almost never took part in councils, treaty sessions, or any kind of meetings with whites or Native Americans. He was a feared and respected warrior, but he did not brag about his war deeds. He did not leave behind any letters, diaries, speeches, or account books to tell his side of the story. The longest recorded statement by him is barely 200 words.

For almost his whole life, Crazy Horse avoided whites. He lived the life of a Lakota warrior, raiding and hunting on the Northern Plains. For about the first 35 years of his life, it is difficult to determine what he said or felt. His biography can only be assembled from the memories and oral tradition of the Lakota people. Truth telling and the oral historical tradition are important in Native American cultures. Storytellers had fantastic memories for remembering minute details. Yet many times, they related their stories of Crazy Horse 25 to 50 years after the events they described. Their descriptions and recollections are crucial, but they are not always accurate. Sometimes, reliable Native American eyewitnesses even contradict each other.

The mid-nineteenth-century Lakota, like most preindustrial people, were not obsessed with dates and statistics. It is almost impossible to determine the year of Crazy Horses birth. The chronology of the events of his life is often jumbled. People have told some stories so many times that the stories have acquired the exaggerations of legend. Without anyone to contradict them, people have felt free to add or change details.

In the last two years of his life, Crazy Horse led the Lakota in two of the most famous battles of the American West: the Rosebud and the Little Bighorn. From this period, a great deal of white and Native American documentation exists; however, the U.S. Army recollections and memoirs often are colored by the cultural assumptions and the racism of the time. Army reports sometimes covered up embarrassing incidents or arguments and often tried to glorify minor engagements into victories or explain away defeats.

Native American testimony from these years, while less biased, is also not reliable. Lakota and Cheyenne warriors worried about white revenge and often deliberately distorted the truth. Plains Indians accounts of battles were usually centered on individuals. They are useful in recalling personal incidents, but they seldom have much to say about group behavior in warfare. There are also problems in the translation of words and phrases.

In the final four months of Crazy Horses life, he lived on a reservation. For this period, there are almost too many witnesses. American and Lakota sources all seem to have an argument to make, a side to take, or a position to prove. Stories contradict each other, culminating in Crazy Horses incredibly controversial death. Historians are unable even to agree whether his death was murder or an accident, a planned conspiracy or a huge mistake. The wealth of material means that most biographies of Crazy Horse spend more than half of their pages on the last two years of his life, from the Battle of the Rosebud to his death.

Next page