Also by Thomas Powers

Intelligence Wars

The Confirmation

Heisenbergs War

Thinking About the Next War

The Man Who Kept the Secrets

The War at Home

This Is a Borzoi Book

Published by Alfred A. Knopf

Copyright 2010 by Thomas Powers

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of

Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Powers, Thomas.

The killing of Crazy Horse / By Thomas Powers.1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-59451-8

1. Crazy Horse, ca. 18421877Death and burial. 2. Oglala IndiansKings and rulersBiography. I. Title. E 99.03 C 7255 2010 978.0049752440092dc22 [ B ] 2010016842

v3.1

For Halley and Finn,

Toby and Quinn

CONTENTS

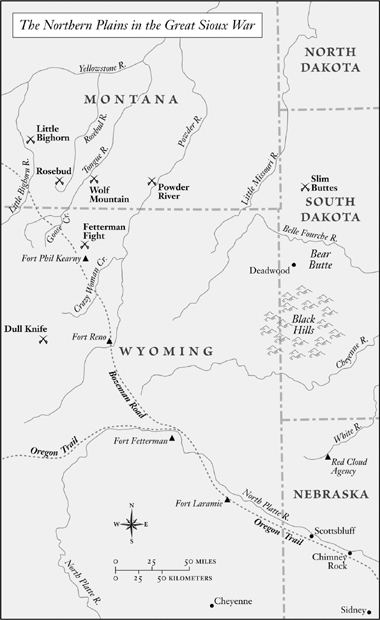

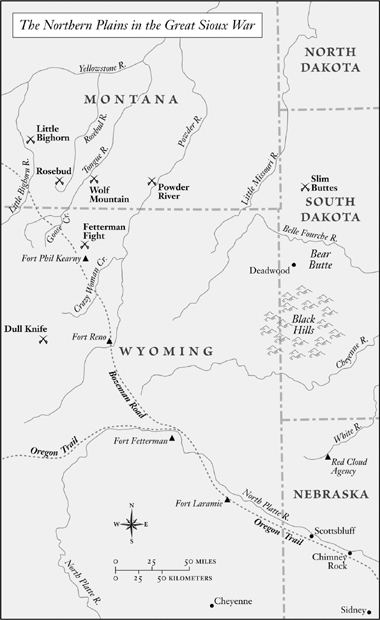

MAPS

INTRODUCTION

Well come for you another time.

The half-Sioux interpreter William Garnett, who died a dozen years before I was born, first set me to wondering why Crazy Horse was killed. He made it seem so unnecessary. I read Garnetts account of the killing in a motel at Crow Agency, Montana, not two miles from the spot where Crazy Horse in 1876 led a charge up over the back of a ridge, splitting in two the command of General George Armstrong Custer. Within a very few minutes, Custer and two hundred cavalry soldiers were dead on a hillside overlooking the Little Bighorn River. It was the worst defeat ever inflicted on the United States Army by Plains Indians. A year later Crazy Horse himself was dead of a bayonet wound, stabbed in the small of the back by soldiers trying to place him under arrest.

Dead Indians are a common feature of American history, but the killing of Crazy Horse retains its power to shock. Garnett, twenty-two years old at the time, was not only present on the fatal day but was deeply involved in the unfolding of events. In 1920 he told a retired Army general what happened. A transcript of the conversation was eventually published. Thats what I read lying on my back on a bed in Crow Agencys only motel.

It was Garnetts frank and thoughtful tone that first caught my attention. He knew the ins and outs of the whole complex story, but even near the end of his life he had not made up his mind how to think about it. Garnett was present on the evening of September 3, 1877, when General George Crook met with thirteen leading men of the Oglala Sioux to plan the killing of Crazy Horse later that night. A lieutenant who had been working with the Indians promised to give two hundred dollars and his best horse to the man who killed him. The place was a remote military post in northwest Nebraska, a mile and a half from the Oglala agency, as Indian reservations were called at the time. Pushing events was the Armys fear that Crazy Horse was planning a new war. Then came a report from an Oglala scout named Woman Dress that Crazy Horse was planning to kill Crook. Something about that story aroused doubts in Garnett when he heard it. Crook was a little in doubt himself. He wanted to know if Woman Dress could be trusted. The answer was close enough to yes to propel events forward.

In the event, nothing went according to plan. Killing the chief that night was altered to arresting him the following day, but that plan ran into trouble as well. It was not the Army that finally seized Crazy Horse in the early evening of September 5, 1877, but Crazy Horse who gave himself up to the Army, then walked to the guardhouse holding the hand of the officer of the day. The chief had been promised a chance to explain himself to the commanding officer of the military post, and he trusted the promise until the moment he saw the barred window in the guardhouse door.

In my experience the seed of a book can often be traced back a long way. This one began with a childhood passion for Indians. It was acquired in the usual way, picked up on the playground in the 1940s and 50s when the game of Cowboys and Indians enjoyed a last flowering. Hopalong Cassidy, Roy Rogers, Gene Autry, and the Lone Ranger were predictable staples of kids television, in my view, but the game itself, played with cap pistols across suburban backyards, invited somebody to take the part of the Indians.

From the beginning I thought cowboys dull, Indians mysterious, compelling, and something that did not fit easily into the gametheir road had been a hard one. Kids have quick sympathies, and mine took shape early. My father helped them form with the books he gave me, which went beyond the usual fare. I still own a lot of the books that kept me up late when I was twelve and thirteen: James Willard Schultzs My Life as an Indian, Mari Sandozs Cheyenne Autumn, Edgar I. Stewarts Custers Luck. They gave me a lifelong appetite for the particular, and a solid grasp of certain truths. One was the fact that the Indian wars were about land, and specifically about removal of Indians from land that whites wanted. Another was the existence of sorrow and tragedy in historyloss and pain that cannot be redeemed. That was not the way I would have put it at the time, but I got the central idea clearly enough. By the time I was fourteen I understood that the treatment of Indians was something people did not like to describe plainly.

Then I grew up. I quit reading about Indians and was caught up by other sorrows, tragedies, and moral complexities. I became a reporter and moved from one subject to another in a progression that always seemed to make sense. The antiwar movement was the first thing I wrote about seriously. From that I learned something about intelligence organizations, and wanted to know more. Study of that in its turn brought me to the history of nuclear weapons, and eventually I was prompted to wonder why the Germans in World War Two failed to build an atomic bomb of their own. Each of these subjects involved much that was hidden, and each absorbed years of work. That was the personal history I brought to Crow Agency in 1994 when my brother and I decided to spend a couple of days at the Little Bighorn battlefield.

The voice of William Garnett thus found a ready listener. What he said prompted many questions. I hadnt thought about Indians for decades, but Garnett brought me back around. Nothing quite opens up history like an eventthe interplay of a large cast pushing a conflict to a moment of decision. It is the event that gives history its narrative backbone. Very often the excavation of an event can reveal the whole of an era, just as an archeologists trench through a corner of an ancient city can bring back to light a forgotten civilization.

But I confess it was wanting to know why Crazy Horse was killed, not the abstract lessons to be drawn from his fate, that drew me on. Its my working theory that pinning down what happened is always the first step to understanding why it happened. Thats where the appetite for the particular comes in, the who, what, and when. Those who watched or took part in Crazy Horses killing seemed to understand immediately that something troubling had occurred, but the publics interest ended with a week of newspaper stories. No official called at the time for a public accounting, and none was made. Histories of the Great Sioux War have treated the killing as regrettable but forgettable, something between a footnote and an afterthought. The event itself remained obscure, muffled, sketchily recorded. In the histories, William Garnett was typically given a sentence or two, if his role was noted at all.