I zaak Walton was my excuse to go to England. I had been thinking through ideas to get money from Yale in the form of a traveling fellowship for two years, and several attempts had failed. The most notable of these was my proposal to fish the headwaters of the Tigris River in Eastern Turkey, the site of Eden in Miltons Paradise Lost. Id told the judges on the committee that I thought I would glean some great wisdom from catching trout that were descendants of those which had witnessed mans fall from Paradise. They didnt bite.

My more realistic approach, which was still a hard sell, was that I was going to fish in the footsteps of a legitimate seventeenth-century author, Izaak Walton. You know, hes the guy who wrote The Compleat Angler, the book that everyones heard of but not everyone has read. Its the third most frequently reprinted book in the English language after the Bible and the worksof Shakespeare, I told the committee, it went through over four hundred editions in three hundred years. I told them during my interview that Waltons words spoke to me, that fishing was my passion, and that his book represented and defended every facet of the art of angling more lucidly than I ever could. I lied; at that point I hadnt even read it.

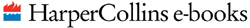

Shortly after I won the fellowship, I read the Compleat Angler cover to cover and began to believe my lie, or at least my lie had become a prophesy that was being fulfilled. The book settled my mind and pulled me into both its pastoral fantasy and its philosophies concerning the timelessness and immortality achieved through fishing. I began to draw out my route, to imagine where I would go, and the places I wanted to touch that perhaps Walton had. I wanted to see his ghost, the ghost of this great and humble man who during the English Civil War, one of Britains most turbulent times, wrote this seemingly simple and wonderful book that would become the most widely acclaimed piece of angling literature, moving beyond the cultish circle of fisherman and into the mainstream.

Walton was sixty when The Compleat Angler was published, a sage man whom everyone liked, a man who was a simple tailor but because of his genial nature had won the company of kings. I began to identify with Walton; I was simple too, a Connecticut Yankee whose intention now was to enter the highest classes of English society, to fish in the backyards of lords and princes and to make them my friends. Fishing was a common bond that would break all boundaries. And when some American gentleman at one of my talks suggested that my winning the fellowship to go fishing in England was a boondoggle Igot defensive. I wanted to strike him down with my defense of angling armed with Waltons words.

Fishing is my religion and the trout stream is my temple. Izaak Walton was the anglers Messiah, and I was prepared to go on this pilgrimage to England and meet the people who were connected with Waltons ideals. I didnt exactly know what I would find, but I was going, and had sent letters to key people who owned private water to ask if I may fish. If I didnt get permission I figured Id trespass; as far as I knew theyd stopped beheading people for poaching. But even after I got permission to fish in what I would come to realize were some of the best trout waters in the world, I felt like a spy, as if I were stealing the kings game, that I was invading a foreign society. I felt like Alice must have felt in Wonderland or like the Connecticut Yankee in King Arthurs court; I was in this strange and beautiful world where everyone was mad, completely batty, except me. It felt like I had mistakenly walked into an asylum.

Dont let the similar language thing fool you, my British friend warned me when he picked me up from the airport, England is very different from America. He was right, they drove on the wrong side of the street.

And where did Walton fit into all this? He was the reason I was there. I had a plan, I was going to visit the fishing temple his friend Charles Cotton built on the river Dove, the place where they used to hang out and discuss angling after a day of fishing. I heard it still existed and I wanted to touch it. The temple became the object of my pilgrimage.

And I had to trespass to get to it: the American way! In fact, the American way worked the whole time I was there. While I was dressed in a T-shirt and jeans, anglers I came across were in their Burberry tweeds and ties, but I caught more fish than they did. I taught them a new cast(e) system, these strange people in England; an Englishman couldnt have done what I did. They didnt admit it but they admired Americans.

This book is about the people Ive met and some places Ive been; it is about my budding love affair and exploration with the English language and how fishing provided our introduction. As Waltons was, this book is a defense of angling, and in being a defense of angling it is a justification of the life I have lived until this point. In an effort to show that the trials that Walton endured and the things he said about life are still relevant, through the course of this story I will draw parallels between his life and mine. This text, therefore, inevitably leans toward the autobiographical. Books on Walton have been written, many biographies of his little-known life as well as his times, and writing another, without displaying my own feelings, even if I had some startling new evidence about his sexuality or something, in my opinion would be worthless. Im exploring why Walton and his book have survived for almost three hundred and fifty years, and in doing so hope to revive the popularity his works have at times enjoyed. Waltons originality as an author is striking, and we wonder as we read him, as well as about him, how a man born so humble, a tradesman, could have evolved into one of the most gifted literary innovators of his time. When one begins to read Walton it becomes apparent immediately that he had an extraordinary gift for friendship, and what makes him so appealing is that he extends this friendship to his readers and invites us to follow through this pastoral fantasy world to the trout stream:

You are well overtaken, Gentlemen, a good morning to you both; I have stretched my legs up Tottenham-hill to overtake you, hoping your business may occasion you towards Ware, whither I am going this fine fresh May morning.

M any of the discoveries and advances that have surfaced along the river of my life have been serendipitous consequences of my passion for fishing. My essay for college entrance was on ice fishing, and the man who interviewed me at the Yale admissions office was a fisherman. I matriculated at Yale and on the second day of school in New Haven, I joined the crew team because they rowed on the Housatonic River where I grew up fishing. Sophomore year I entered a contest for book-collecting sponsored by the rare-book library at school and won with my collection of trout books, introducing me to the community of Yale bibliophiles. Junior year my own book on trout was published, and suddenly it was no longer taboo to talk about fishing during dates. My senior-year roommate and I put our affinities for singing and acoustic guitar playing together in our band called Trout, playing our original tunes at local coffeehouses, which did even more for my dating life. So you see, when it came time to write my senior essay for the English major, it was only natural that I choose for my subject Izaak Walton and his book