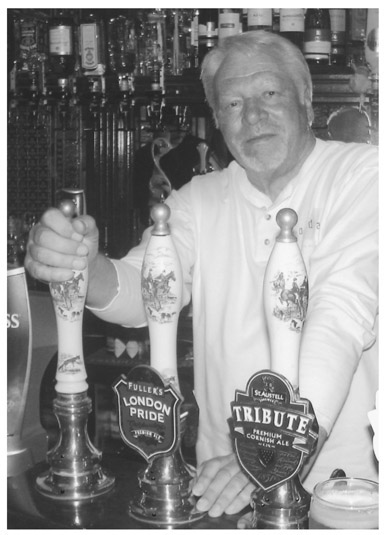

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Sam Lowe has lived in and been writing about Arizona for the past forty-five years. During that time, his stories have appeared in such publications as Arizona Highways, Arizona Highroads, Robb Report, Arizona Republic, Phoenix Gazette, Phoenix Magazine, International Tours and Tourism News, and the Columbus Dispatch. He has also written twelve books about the state, including Speaking Ill of the Dead: Jerks in Arizona History, Arizona Curiosities, and You Know Youre in Arizona When... for Globe Pequot. In April 2009 he was named the Senior Travel Expert for Best Western International. Lowe lives in Phoenix with his wife, Lyn, and his dog, Zachary, both faithful and loyal companions.

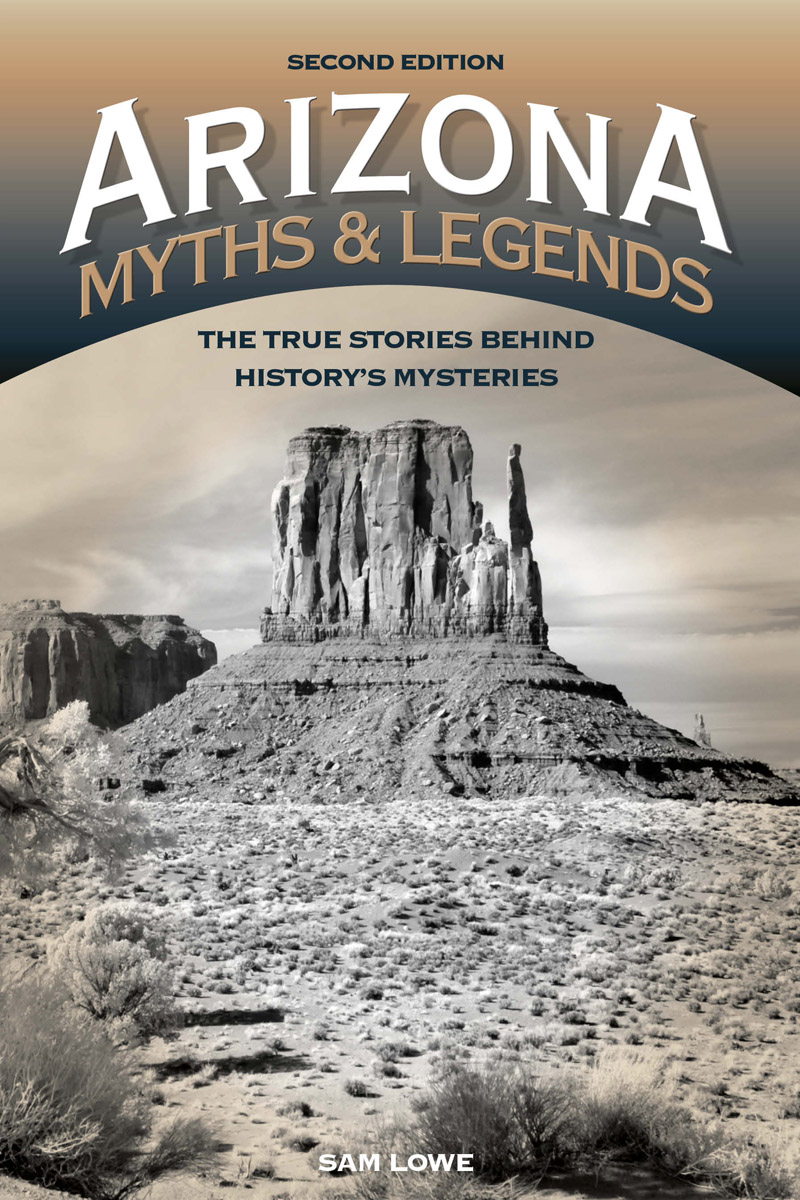

ARIZONA MYTHS & LEGENDS

A TWODOT BOOK

An imprint of Rowman & Littlefield

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2016 by Rowman & Littlefield

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Information available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

ISBN 978-1-4930-2304-2 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-4930-2305-9 (e-book)

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

INTRODUCTION

F irst, a matter of clarification: This is not intended to be a reference book. Rather, it is a collection of stories based on fact. It also includes, however, large doses of supposition, suggestion, hearsay, secondhand information, folklore, saloon and barroom recollections, old wives tales, speculation, and even a smattering of outright fibbing. But quite naturally, all of these are vital content in a publication dealing with myths, mysteries, and legends, which this one does.

I gathered the information from newspaper clippings, magazine articles, websites, reference books, autobiographies, and personal interviews, so it is as factual as I could make it. But regardless of my efforts, it was inevitable that some of those aforementioned elements would slip into my accounts. And, I must admit, I gleefully included them.

The people mentioned herein are long since departed, but their stories live on, usually through books like this. And through supposition, suggestions, hearsay, secondhand information, folklore, saloon and barroom recollections, old wives tales, speculation, and fibs.

So read it with that understanding.

And, of course, enjoy.

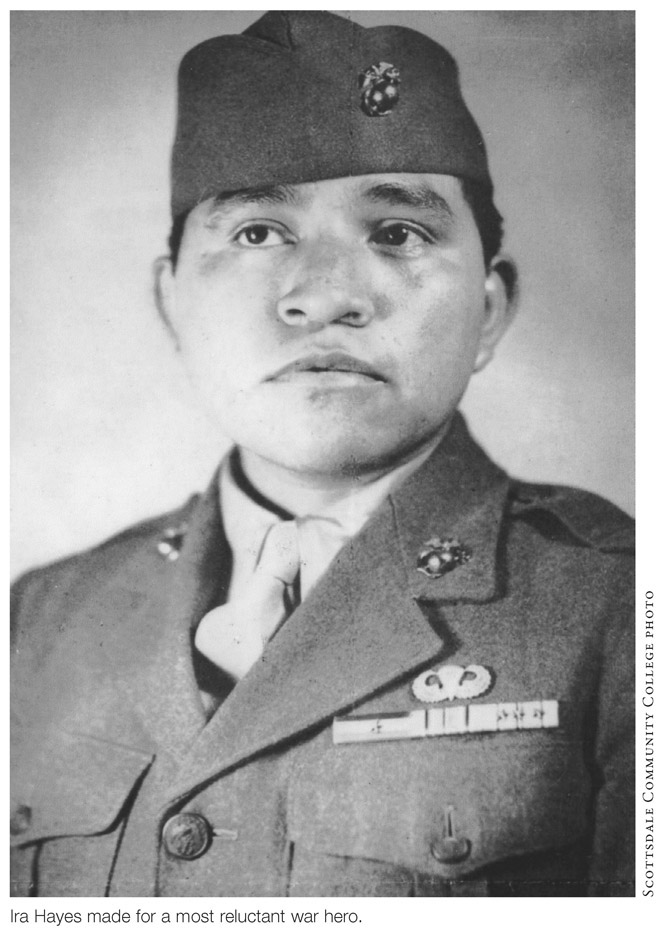

IRA HAYES: ARIZONAS RELUCTANT HERO

I n the chill of the early morning hours of January 24, 1955, members of the Gila River Indian community found the body of one of their friends lying cold near a canal on a patch of desert near Bapchule, a small reservation town south of Phoenix. They recognized him immediately. It was Ira Hayes.

Ira Hayes.

An American legend, dead at such an early age.

A reluctant hero who became a sacrifice during the Second World War.

His tormented life was over. He was only thirty-two years old. But his last few years were a living hell, ignited by the horrors of combat and fueled by well-intended but misplaced homage. Now those who knew him best silently hoped that, in his death, he might find the peace that had eluded him for so many years.

The coroners report listed alcohol and exposure as the major causes of death. It made no mention of either grief or torment, although these surely played a part.

History may record Ira Hamilton Hayes as a hero but, in his own eyes, he neither deserved nor wanted the designation. The government and the military promoted him as an idol and a grateful America accepted him as one. Then once his time in the national spotlight was over, he became a victim, a man who never asked for public acclaim but had it thrust upon him.

And it ruined his life.

Ira Hayes was a Pima Indian first, then a marine, then an unwilling hero. The act that ushered him into a wholly unwanted lifestyle was a chance happening, not a brave deed. He just happened to be there when a single moment immortalized him. He was forced to go along for the ride, regardless of where it took him.

The events leading up to what would become his downfall began on February 19, 1945. American military forces invaded Iwo Jima, a small but strategic island in the South Pacific about seven hundred miles south of Tokyo, Japan. It was a possible supply point for the Allied forces, who considered it important that they prevent the Japanese from using it themselves. Hayes was a part of a landing team met with withering, never-ending fire from the Japanese forces who held the tiny piece of land. Four days later, on February 23, the invaders had captured enough ground to take control. The officers in charge ordered a flag-raising ceremony atop Mount Suribachi, the highest point on the island at 516 feet above sea level.

But the flag they hoisted was deemed too small by the higher-ups, so they gave the order for a second ceremony. This time, armed with a larger flag and accompanied by photographer Joe Rosenthal and about forty fellow servicemen, five marines and a navy corps-man hiked to the top of the peak and planted the second banner. Rosenthal, an Associated Press cameraman, snapped the picture. Days later, the photo appeared on the front pages of newspapers all across America. The act of raising the flag was hailed with all the plaudits that normally accompany great feats of heroism.

It was the first step along a path that would lead to tragedy for five of the six young servicemen shown in Rosenthals photograph.

Three of the flag raisersSgt. Mike Strank of Pennsylvania, Cpl. Harlon Block of Texas, and Pvt. Franklin Sousley of Kentuckydied as the fighting continued on Iwo Jima. The other three were selected to tour the United States as spokesmen for war bond rallies. Each handled the assignment differently. John Bradley, the navy corpsman from Wisconsin, did his duty but then kept his role in the incident a secret, hiding it even from his family, who never knew about it until after his death in 1994. Pvt. Rene Gagnon of New Hampshire tried to capitalize on his fame but it led to business failures, divorce, and alcoholism, culminated by a premature death in 1979.

And Ira Hayes, the Pima Indian from Arizona, tried to run from it only to become a martyr.

Rosenthals image (which shows Hayes at the far left) was awarded a Pulitzer Prize and eventually became the worlds most reproduced photograph. The fight for Iwo Jima stands as the worst battle in Marine Corps history with more than twenty-two thousand casualties, more than they sustained during several months of battle at Guadalcanal.

Ira Hayes was not among them.

Not at first.

But he was most definitely a casualty.

These days, few people on the Gila River Indian Reservation remember the man behind the story. He was born on the reservation on January 12, 1923, and died there a little more than thirty-two years later. He was a member of the Pima tribe, the eldest of eight children. Although shy and introverted, he earned good grades at Sacaton and the Phoenix Indian School. He left high school after completing two years of study to serve in the Civilian Conservation Corps for a couple of months before taking a job as a carpenter. On August 26, 1942, he enlisted in the Marine Corps Reserve at Phoenix for a period referred to by the federal government as the duration of the national emergency. After giving its approval, the tribe sent one of its sons off to fight. It was tradition, in a way. The Pimas had always been known as protectors.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.