ORDINARY THINGS

ORDINARY THINGS

A DIFFERENT KIND OF VOYAGE

Christopher

PRATT

EDITED AND WITH A FOREWORD BY

TOM HENIHAN

BREAKWATER

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Pratt, Christopher, 1935

Ordinary things : a different kind of voyage / Christopher Pratt.

ISBN 978-1-55081-264-0

1. Pratt, Christopher, 1935- --Diaries.

2. Painters--Canada--Diaries. 3. Newfoundland and Labrador--Biography.

I. Title.

ND249.P7A2 2009 759.11 C2009-902808-5

2009 Christopher Pratt

Editor: Tom Henihan

All images from the authors personal collection, except as noted

Author photograph: Ned Pratt

Cover image Collection RBC Financial Group

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

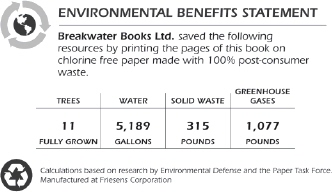

BREAKWATER BOOKS LTD. acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts which last year invested $20.1 million in writing and publishing throughout Canada. We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program for our publishing activities. We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador through the department of Tourism, Culture and Recreation for our publishing activities.

Printed in Canada

Table of Contents

I AM indebted to Breakwater Books, especially Rebecca Rose, Clyde Rose, Annamarie Beckel and Anna Kate MacDonald, for their support and enthusiasm for this project. It originates from many years of notes, diaries, boat logs, and car books, skipping along their surfaces like a stone on a rippled pond, avoiding for now its depths. Rhonda Molloy brought her own understanding of St. Marys Bay to its design and layout; Chad Pelley has been entirely respectful of the voice and origins of these often-rambling entries. They have all been very responsive to my concerns and objectives, and effective in their realization.

My thanks to poet and editor, Tom Henihan, whom I first met when he edited A Painters Poems, for his guidance in the selection of material included here from a much wider, but necessarily limited base, and for the counsel, sensitivity, and advice he brought to the process of adjusting the language of the diary for a wider audience, while preserving its voice and respecting its codes.

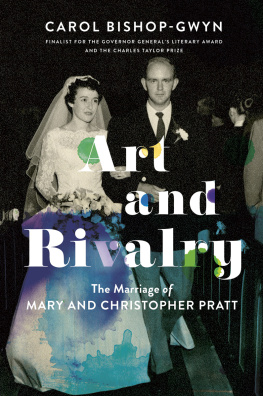

My secretary, Brenda Kielley, has exhibited characteristic patience and professionalism throughout what seemed to be endless adjustments and changes. My children, John, Anne, Barbara, and Ned, and my brother Philip, continue to meet me with care, humour, and forbearance. Many friends and colleagues, in particular the poet Tom Dawe, Tom Smart, Director of the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, and Mira Godard and Gisella Giacalone at The Mira Godard Gallery, have been helpful, encouraging, generous in their understanding, and wise in their cautionary verse. Nor do I forget the profound contribution Mary West Pratt has brought to my work and my life.

My wife and assistant, Jeanette Meehan Pratt, gallantly takes the blame for every bump and pothole in the road that jars my hand as I write, while she drives, and we go in search of this wonderful province much of it already familiar to me, most of it new to her. Her company and enthusiasm enriches all of it.

I have always been surrounded by tolerant, intelligent, caring and compassionate people friends and family alike. I thank them all, many now, sadly, in absentia. They in habit this book at its centre, or just off stage. It is dedicated to them, and in particular to my parents, Emily Christina Dawe and John Kerr Pratt, who were known to their friends, ordinarily, as Chris and Jack.

Christopher Pratt

July 7, 2009

Salmonier

CHRISTOPHER PRATT has written all of his life, marking the ordinary days and events of his life, and those framed by special significance and circumstance. Whether he is writing on a matter of obvious importance or something apparently less decisive, everything is afforded the same consideration. This is consistent with the inherent belief, expressed in a number of different contexts in this book, that the significance things have is the significance we bring to them. In a piece written in 1975, he speaks about his own early awareness in this regard, I believed that picturesque, photogenic, beautiful or even magnificently ugly things had no more claim to precedent than the unadorned, unlit cupboard door outside my bedroom. The sun, a mighty presence, had no greater reality than the 40-watt bulb whose terrestrial energy it had ordained. He finishes the piece by saying, In the face of it, all things are equal in the fact that they exist.

This book is composed of pieces from journals and diaries written from the 1950s to the present, covering a broad spectrum of subject matter and a variety of genres: travel pieces, epigram, humorous anecdote, prose poems. But it is not fragmentary an undertaking as important as his 2005 retrospective, the triumphs and frustrations of a painters life, sailing from Lake Ontario to Conception Bay, Newfoundland, time spent with family and friends, hiking in the Tablelands, or sitting alone on the deck at night at his home in Salmonier, are all rendered as integral aspects of a single picture. While the pieces in this book constitute the story of a life, it is neither autobiography nor memoir, but more accurately, as Christopher Pratt himself has described it, a self-portrait.

Tom Henihan, 2008

I HAVE always had a sense that there is an immense presence in ordinariness. This ordinariness is not a celebration of the sordid or the tawdry or the trite: it celebrates the non-exotic, the anti-picturesque. Conceptually, it is totally North American: it is Hoppers hotel rooms and Hemingways descriptions of Nick Adams and Alex Colvilles cows. It is that substrate of self-consciousness and insecurity that troubles the surface bravado of Walt Whitmans poetry; it is Grant Woods innocence in offering American Gothic up to ridicule. It is why Mary Cassatt ought not to have gone to Paris and why Georgia OKeefe and Emily Carr did better staying home. It is the difference in the albeit mannered peopling of paintings by Thomas Hart Benton and the peasants in the work of Jean Francois Millet who still owed much to Maccicio. It is Shaker furniture, but it is never puritanical. It is the dignity of things that have nothing going for them beyond the fact of their existence. It is an ordinariness saturated with democracy, with potential, like the hum you hear in a length of rope stretched to its limit, just before it breaks.

MY APPENDIX abandoned me at the Grace Hospital in St. Johns on Thursday, July 17, 1952, Dr. Harry Roberts presiding. That was the summer I graduated from Prince of Wales College.

I had a string of encounters with what we then called summer complaint. My mother, who had seen a lot as a nurse in Montreal and St. Johns, got nervous about my symptoms so she and Harry decided that it was better to be safe than sorry. As a result, I had the surgery and spent much of that summer convalescing in our back garden on Waterford Bridge Road while my buddies were off trouting, swimming, courting

Next page