Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

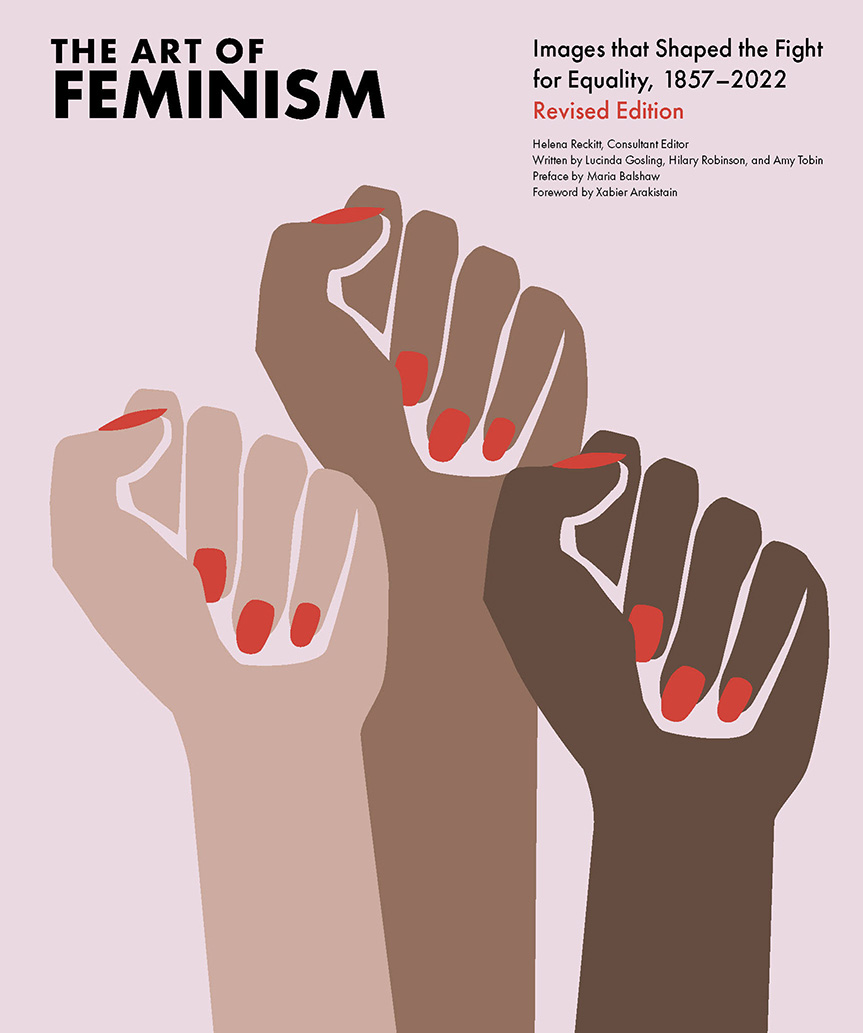

About the cover art:

Femme Fists by Brooklyn-based designer Deva Pardue was created in response to the results of the 2016 presidential election in the United States. Its rooted in the belief that issues of gender, ethnicity, and race cannot be separated. The now-iconic image went viral during the 2017 Womens March, when it was shared widely and carried in womens marches all over the world. Pardue has leveraged the illustrations popularity to raise money for womens rights organizations such as the Center for Reproductive Rights, Emilys List, the Joyful Heart Foundation, She Should Run, and Safe Horizon.

Copyright 2018, 2022 Elephant Book Company Limited

This 2022 edition is published by Chronicle Books by arrangement with Elephant Book Company Limited, Purcell, St. Marys Hall, Rawstorn Road, Colchester, CO3 3JH, United Kingdom

constitute a continuation of the copyright page.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-7972-2038-3 (epub, mobi)

ISBN: 978-1-7972-1754-3 (hardcover)

Cover: Femme Fists illustration copyright by Deva Pardue, For All Womankind, www.forallwomankind.com

Editorial Director: Will Steeds

Executive Editor: Joanna de Vries

Project Editor (revised edition): Lucy Doncaster

Project Editor (original edition): Anna Southgate

Book Design: Paul Palmer-Edwards

Picture Research: Sally Claxton; Katie Greenwood

Proofreader: Marion Dent

Indexer: Cheryl Hunston

Proofreader and indexer (revised edition): Paula Clarke Bain

For Chronicle Books: Natalie Butterfield

Chronicle books and gifts are available at special quantity discounts to corporations, professional associations, literacy programs, and other organizations. For details and discount information, please contact our premiums department at corporatesales@chroniclebooks.com or at 1-800-759-0190.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

Contents

Preface

Maria Balshaw, Director of Tate, London, U.K.

I write this preface after a weekend in 2018 where the United Kingdom witnessed a feminist performance on an epic scale. Many tens of thousands of women, in London, Glasgow, Newcastle, and from across the whole country, became Processions a mass-movement art performance marking 100 years since partial suffrage was granted in the United Kingdom.

This collective performance, with women carrying and wearing banners and costumes in the purple, white, and green of the suffragette movement, created a feminist spectacle that closed the center of London as both protest and celebration. This two-fold orientation speaks of the gender conflicts of the past one hundred years, and the issues and challenges that are still part of our now. A more than one-hundred-year view is the admirable aspiration of this important text. This book reminds us, as Processions does, how feminism has always been a plural and intersectional movement, even if this has not always been acknowledged or properly addressed. The United Kingdoms 1918 suffrage victory was, of course, a limited emancipation of some white women and too many decades passed with change being felt in unequal measure across the differences of race, ethnicity, sexuality, and class.

The optimism of our now is that art and social mores are moving in nonbinary directions and, as this book vividly documents, we see an ever more plural feminist art practice meeting an engaged activism that seeks to shape an intersectional world view beyond gender and other hierarchies. In seeking to represent over a century of change, this collectively authored text allows us to see the long history of this kind of thinking in the practice of artists and to notice the ellisions and omissions we now also need to own. In taking us from the art of the original suffrage banners to the gender fluid activism of the present day, The Art of Feminism sets out in plain language the, as yet, incomplete story of feminist emancipation. We are all on that procession and there is still some way to go. As a feminist Director of Tate, I salute the multiple and contested practices of artists working within the wide variety of feminist paradigms traced by the authors and I commend the authors for their determination to encompass many world views.

Foreword

Xabier Arakistain, feminist curator, Bilbao, Spain

It was only fifty years ago that, lifted by the feminist activism of the 1960s and 1970s, women became permanently and centrally involved in art theory and practice. It was in that context, echoing Virginia Woolfs proposition about women and literature in A Room of Ones Own , that American art historian Linda Nochlin first applied the renewed feminist perspective to art history with her now legendary article Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?, published in Artnews in 1971.

Nochlins article revealed that art is one of the institutions that reproduce the enduring sociosexual order that maintains and perpetuates masculine hierarchy, which in those years came to be designated by a new term: the patriarchy. Nochlins article inspired a series of studies, publications, and exhibitions devoted to recovering female artists who had been ignored or undervalued by official art history. It also provided the basis for a new paradigm of historiographical and curatorial practice that, at the risk of oversimplification, aims to include women and their work in the discipline.

Some felt this approach was insufficiently transformative because it would fail to incorporate the knowledge and political and social agenda of feminism. A decade later, in 1981, British art historians Griselda Pollock and Rozsika Parker published Old Mistresses: Women, Art and Ideology , in which they affirm that, contrary to popular belief at the time, women have always made art, and had not been systematically erased from the history of art until the twentieth century. They add that art made by women has been categorized as minor under the negative stereotype that they lacked creativity and were therefore unable to contribute to or influence the course of art. They stress that rather than merely being a means of excluding women, such stereotypes are absolutely foundational in the current construction of the discipline of art history and its canons. Therefore, they object to presenting the history of women in art merely as a struggle for inclusion in institutions such as art academies. In their view, this approach conceals the ways in which women have succeeded in making art in different contexts, despite being constrained as much by their sex as their class. Moreover, they emphasize that if we only see womens history as a progressive struggle for inclusion against great odds, we are falling into the trap of reaffirming the assumed, established, and often unconscious norms of the field as it has been shaped by men and male dominance. Finally, Parker and Pollock openly question the belief that women should fight for recognition in the current status quo, rather than focusing on dismantling it. In Old Mistresses , they establish the basis for the question that Pollock would ask in 1994, namely: Can art history survive feminism? She argues that, in her attempt to understand the nature and effects of feminist intervention, she cannot confine herself to the strict domain of the history of art and its discourse in the context of art history: to understand the effect of feminism she has to go far beyond art historical critical and interpretative schemas. In turn, Pollocks perspective has also inspired another historiographical and curatorial practice, focused on exhibiting and explaining the work of women artists from positions and terms different from those of dominant art criticisma practice that Pollock herself has continuously explored. A valid objection to this approach is that the process of reevaluating artworks made by women may in some instances lead to a lack of critical appraisal of such works as a product of a specific patriarchal power relations.