I sought the advice and opinions of many wise people in the preparation and execution of this book, but still went ahead and wrote it anyway. Sincere thanks to Alan Samson for his encouragement and faith from the books very inception, to Richard Beswick and particularly Sarah Shrubb for all their advice and input, and to Lizzy Kremer for being the worlds greatest agent. Special thanks also to Hilary Hale.

Big thanks are due to Andy Yeatman and Martin Rowley at the Met Office, and Jane Watson, David Anderson and Nikki Richardson at BBC Radio 4.

Daphne Caine at the Isle of Man governments Department of Tourism (www.gov.im/tourism/) was helpful way beyond the call of duty, while I am also particularly indebted to Lisa Morgan at Braathens (www.braathens.no) and Bill Tinto at Scotia Travel (www.scotiatravel.com) for their assistance.

Thanking everyone who helped to make my job easier would take up a whole extra volume, but Wenche Ringstrand, Jo Heuston, Julie Robson and Clive Ramage, Brian Rees, Donald and Eileen Cowey, Mike With, David and Nessie Taylor, Matt Wright, Campbell Scott, Lew and Prince Michael of Sealand, Tim Bennett, the Broadstairs Babes, Sam Lacey, Mum and Dad, Roy and Sandy Sands, Hugh MacDonald, J.R. Daeschner, Lola Brown, Mick Collins, Paul and Emma sJacob, Tim and Elizabeth OBrien, Douglas Greig, Helen Carter and Emma Murray all provided invaluable assistance, encouragement and in some cases terrific travel companions. There are many people I havent mentioned here by name, mainly because I am completely disorganised and forgot, but a great big Thanks, folks and a (strictly metaphorical) round of drinks to everyone.

Special thanks and much, much love to Katie for putting up with my frequent absences, rank disorganisation and chronic untidiness. As usual, I couldnt do it without you.

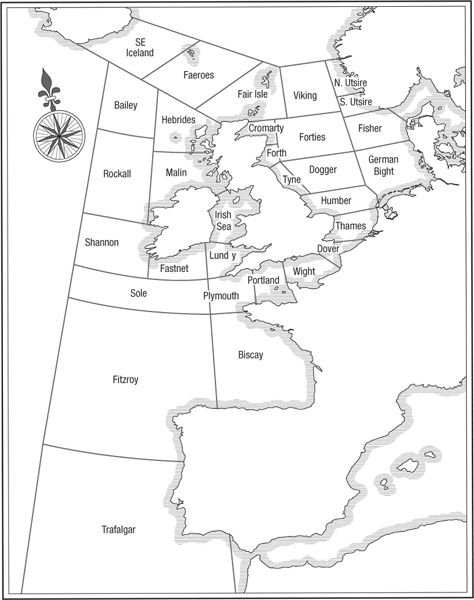

The solemn, rhythmic intonation of the shipping forecast is as familiar to us as the sound of Big Ben chiming the hour. Since its first broadcast in the 1920s it has inspired poems and songs in addition to its intended objective of warning generations of seafarers of impending storms and gales.

Sitting at home listening to the shipping forecast can be a cosily reassuring experience. Theres no danger of a westerly gale eight, backing south-westerly increasing severe gale nine later (visibility poor) gusting through your average suburban living room, blowing the Sunday papers all over the place and traumatising the cat. The chances of squally showers, moderate or good becoming poor later, drenching your new sofa and reducing the unbroken two-year run of Hello! magazines under the coffee table to a papery pulp are frankly slim unless theres a serious problem with your radiators. Theres definitely something comforting about the fact that although some salty old sea dog in a draughty wheelhouse somewhere will be buttoning his souwester even tighter at the news there are warnings of gales in Rockall, Malin and Bailey, you can turn up the central heating and see if theres a nice film on the telly. The Cruel Sea, perhaps.

Oddly comforting though the shipping forecast is, to most of us it is totally meaningless. A jumble of words, phrases and numbers which could be thrown into the air, picked off the floor and read out at random and most of us wouldnt be any the wiser. It has, however, accompanied most of our lives from childhood, a constant, unchanging cultural reference point that goes back further than Coronation Street, the Ovalteenies and even the Rolling Stones. No one, not even the most committed mariner, listens to all four broadcasts every day. In fact very few of us make a point of listening to the shipping forecast. But its always there, always has been, always will be, lodged inexplicably in our subconscious. Stop anyone in the street and ask them to name as many of the areas as possible and the chances are theyll get through about half a dozen before even pausing for breath. I guarantee Dogger and Fisher will be two of them as well. Ask them how they know these things, and youre likely to receive in response a gaze into the middle distance, a slight furrow of the brow and a Well, er, dunno really .

For me as a small boy, when the shipping forecast came on the kitchen radio just before six oclock in the evening it meant that my tea was nearly ready. It didnt mean any more than that; just a hotchpotch of incomprehensible words that acted as a Pavlovian bell to my tastebuds. In fact, its only recently that the words Forties, Cromarty and Forth have stopped causing me to salivate slightly and think of Findus Crispy Pancakes.

If anything, the sound of the shipping forecast made me think of being safe at home. It also necessitated at least one visit to Greenwich Hospital when the familiar words prompted an uncontrolled hunger-inspired scamper of stockinged feet across polished kitchen lino that was interrupted at full tilt by an unfortunately positioned domestic appliance. Stitches were required. Come to think of it, I could probably blame the shipping forecast for the scar on my forehead that scuppered an otherwise inevitable modelling career.

Childhood visits to casualty aside, for me the shipping forecast retains a soothing, homely aspect to it, which is strange when you think that its contents are anything but soothing and homely. But as I grew up and began to sprout hair in places Id never considered before, and began to live in places Id never considered before, catching the shipping forecast on the radio would always be a comforting experience. The forecast itself might be telling me otherwise, but hearing it meant that everything was all right. No matter how bad things got, no matter how dubious any career or romantic issues became, not to mention global events, the knowledge that the shipping forecast was still going out four times a day, regular as clockwork, meant that everything would be fine. Not, perhaps, for the good people of Hebrides when they heard severe gale nine was heading their way in the next few hours, but the great scheme of things was generally all right. Oh, and my fish fingers were nearly ready.