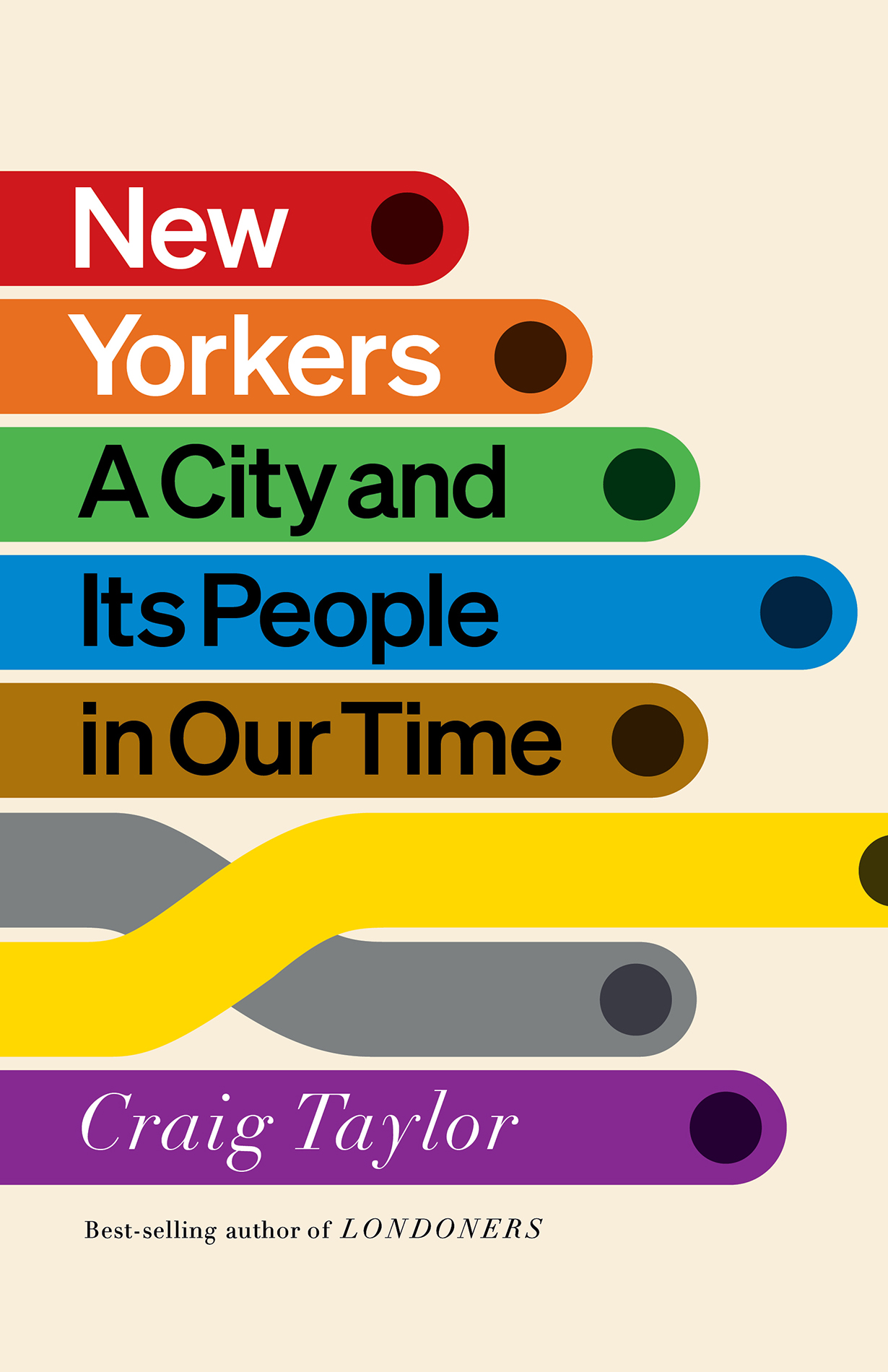

New

Yorkers

A City and

Its People in

Our Time

Craig

Taylor

W.W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

For my father, who made the journey.

What a strange, what a fantastic city... there was something here that one experienced nowhere else on earth. Something one loved intensely. What was it? Crossing the streetsstanding on the street corners with the crowds: what was it that induced this special climate of the nerves... a peculiar sense of intimacy, friendliness, being here with all these people and in this strange place... They touched your heart with tenderness and you felt yourself a part of the real flight and fluttersearching their faces, speculating about their dooms and destinies.

Isabel Bolton, Do I Wake or Sleep

O ne night, on a Manhattan-bound F train, a man pushed his way past me. He stumbled, grabbed at a pole for balance, grabbed at it again, succeeded, stood for a few moments, and finally sat. He placed one hand on a yellow plastic seat, stared at it, and said, More pain. The man lifted his head and addressed a stranger standing nearby: More pain, he said. When the doors opened at East Broadway I stepped out before More Pain Man was pushed onto the platform by the stranger, who followed him for a few steps and kept repeating the words I dont want to fight you before his friends pulled him back onto the F. The train left the station. Now alone, More Pain Man stood on the platform. It was late. The station was empty, so the acoustics were perfect when he yelled out those same wordsa description of what he had already received or a demand for the future, I wasnt sure.

More life, Id been told when I arrived in New York, and more of life. You will hold the inside doorknob of your apartmentI was toldand you will think to yourself, Get ready to enter the oceanic power. Its no use arguing with it. Its no use doing anything but relenting, letting it hit you, moving with that force. In New York you will always get more.

New York meant more of everything. More joy, more sorrow, more pleasure, more pain. More experience, more possibilities to find love, more wealth, and a poverty with more of a sharp, punitive edge. Even if, statistically, New York was now smaller than Baoding and Tianjin and Hyderabad and many others, it still overwhelmed in its old familiar ways. More awe as the skyline rose, more moments of incredulity as light flooded down the canyon of an avenue, and more disgust at what looked to be grease smeared on the back of an Elmo costume in Times Square. More Elmos. More actual height could be found in the skyscrapers of Kuala Lumpur. Still, it just felt like the city held more: more elevators, more LED lights, more nail salons, more rats, more bridges.

Over the course of my years in New York, I felt that pain, but also enveloping love, and I got caught up in more diversion than expected. I was awed by what was endlessly offered up. I loved the concentrate; I loved the proximity to strangers, how every day you were inches from weirdness, greatness, and everything in between. It was the greatest ongoing flicker of human life Id ever encountered. Something or someone came at you in each moment, and what you got, in interactions with the city, was a consistent assault on the senses. Your senses were worked and exercised and reworked every day. I loved the endless sense of and-this-ness: this man, and this woman, and this look, and this detail, and this necklace on that cyclist, and this and thisa richness that sank down beneath you till it hit the serpentinite and schist, the Fordham gneiss and Inwood marble and Hartland formation. Until that point, there was always more. And then you crossed to the next block and started the process all over again. This and this and this.

ALL OF IT WAS NEW to me when I moved to New York in January 2014 to start reporting New Yorkers. I had spent the previous decade researching, reporting, and writing two books about other places. They were based on my experiences interviewing a wide array of people to get a feel for their lives, their work, and the places they made. For the first one, Return to Akenfield, I had spent a couple months in an English village with hunters, farmers, apple pickers, priests, publicans, teachers and shopkeepers, commuters and retirees, and a gnarled old rag-rug maker, all in an effort to capture rural life a generation after Ronald Blythes classic 1969 book, Akenfield. As a follow-up I spent five years walking the streets and squares of London, interviewing Londoners. The book that resulted, Londoners, presented a contemporary portrait of the city from more than eighty voices, street sweepers to investment bankers, a manicurist to a dominatrix.

Neither of those books were about places Id grown up knowing; I had moved to London from a seaside village in western Canada. But not knowing a place, not being of a place, left a space for others to step forward to explain. I imagined there would be no lack of candor. I only knew that I wanted to craft a book about New York in the twenty-first century, filled with the voices and sounds and places and people of New York, the life of the city right now. A book that would capture the richness of its conversation, the complaints and quiet admissions of a city in flux; and one that would weave together the voices of an enormously diverse city: people from every borough, the rich and the poor, young and old, immigrant voices and native, those emboldened by the city as well as those whod felt its sharp edge.

It takes one proof of address to get a New York Public Library card. Mine allowed me to keep going back to James Baldwin and Joseph Mitchell and Vivian Gornick and Jacob Riis, Marianne Moore and Edith Wharton and Langston Hughes, Jane Jacobs, Frank OHara, Bernard Malamud, Oscar Hijuelos, and Ralph Ellison. I had my own copy of Robert Caros The Power Broker and was told that some people couldnt travel with such an enormous book on the subway, so they cut it into thirds. The first incision should be made at page 359, the second at page 828. I kept mine whole.

I was also surrounded by the excellent writing about New York City that comes out every month, every week, every day, every few minutes in the stack of remaining hometown newspapers and magazines, in the New York Times Metro section, as well as the eruption of superb reporting online and on the radio and the commentary that unfurled on the social media feeds of observant New Yorkers. All of this work is vital, intimidating, often entertaining, but I wanted to find something more direct, and to create a kind of oral portrait of the city grounded in the flow of New Yorkers speech.

I took my cue from writers who had walked the streets and done the legwork. From Riiss reports from the filth and degradation of tenement blocks in How the Other Half Lives, and from E. B. Whites Here Is New York a half century later, in which he wrote about strangers who have pulled up stakes somewhere and come to town, seeking sanctuary or fulfillment or some greater or lesser grail. These seekers teemed through New York in the hot summer of 1948 when White wrote the piece; they still fill the sidewalks. It was these sidewalks that seemed to usher forth conversation. I liked books where you could almost see New York conversation rising from the pavement. I started walking the city, and then I started walking with other people, and got to feel the incantatory power of New York sidewalks. In one of my many guides,

Next page