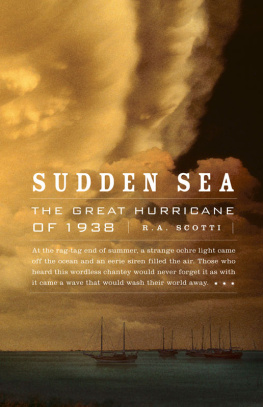

Thirty-Eight

Thirty-Eight

The Hurricane That Transformed New England

Stephen Long

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Calvin Chapin of the Class of 1788, Yale College.

Copyright 2016 by Stephen Long.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Janson Roman type by Integrated Publishing Solutions, Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015945291

ISBN 978-0-300-20951-8 (cloth : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my father, who gave us summers in the woods,

and to my mother, who made those years so much fun

Thomas Long (19112001)

Mary Beers Long (19162013)

Contents

Preface

The hurricane that pummeled the East Coast on September 21, 1938, was New Englands most damaging weather event ever. Call it New Englands Katrina and you might be understating its power. The storm plowed into Long Island and New England without warning, killing hundreds of people and destroying roads, bridges, dams, and buildings. The devastation to the regions infrastructure required repairs costing $300 million in Depression-era dollars, approximately $5 billion today.

Almost every word that has been written about the 1938 hurricane recounts the damage to the built environment and to the people who lived in it. It has been an urban story rather than a rural one, a tale of the coast rather than the inland forest. Thats understandable. Compared with the loss of human life and the destruction of property, damage to trees might seem like a scratch on the fender of a car thats been totaled. Still, our lives dependeither directly or indirectlyon forests, and the destruction of a thousand square miles of forestland remains a story that needs to be told.

Forest ecologists have long seen Thirty-Eight as a touchstone event and have studied its long-lasting impacts across the region, but their impressive work on the role of huge disturbances like this has not reached the layman. Little has been written for public consumption about what happened to the forests of New England, and some of it has been so casually reported that its grossly inaccurate. In a book titled Hurricane!, Joe McCarthy (no, not that Joe McCarthy) notes that New Hampshire lost half of its white pines, which is a reasonable statement. But McCarthy follows that with this whopper: Most of the timber felled by the hurricane was too splintered to be used, except as firewood or as pulp at a paper mill. In fact, the hurricane recovery effort awakened a moribund wood-products industry from the Depression. The administrators of Franklin Roosevelts New Deal were accustomed to big challenges and had shown no timidity in putting the full force of the government into play, so the U.S. Forest Service jumped in and created a new agency to respond to the emergency. It expedited the salvage of billions of board feet of logs, but it had another reason to rid the area of the limbs, branches, and boles that carpeted New England. Forest Service officials feared a wildfire that, once ignited, could spread throughout the region, killing more people and destroying more infrastructure. The scale of the timber salvage and fire hazard reduction meant that the regions worst hurricane was followed by the largest logging job the country has ever seen.

In Thirty-Eight I tell the story of this unprecedented one-two punch through a number of lenses: forest ecology, meteorology, social science, political science, and land management. An event of this magnitude requires a multifaceted narrative because the natural disaster and the human historybefore and aftercannot be separated. Ecology and economy have never been wound more tightly together.

The last time a storm of anywhere near this magnitude had hit New England was more than a century before, in 1815. So many generations had come and gone since then that the possibility of a hurricane had disappeared from the public consciousness, and newspapers the following day proclaimed it New Englands first hurricane. Such an extended period without hurricanes seems inconceivable, given our recent history of extreme weather events. Meteorologists and forest historians tell us that another hurricane of this magnitude could occur at any time. We live in an entirely different world from the one laid low in 1938. In Thirty-Eight I examine the ways those differences will influence how destructive the next hurricane will be.

If you have an interest in New England history, forests and trees, or extreme weather events in a changing world, pull up a chair. This is a book about forests and people. We are part of nature. We have changed nature profoundly, but still our forests sustain us economically, ecologically, and spiritually. In Thirty-Eight, I tell the story of a remarkable hurricane and show how a combination of natural disturbance and human actions has created the world we live in. More than seventeen million people now live within the area affected by the hurricane. The green landscape that surrounds us might seem like a comfortingly stable backdrop for daily life, but it is a dynamic system changing every day. And every once in a great while, an explosion of change bursts across a wide area in a way that people never forget.

Acknowledgments

I completed much of the research for this book as a Charles Bullard Fellow at Harvard Forest. I am grateful to the researchers and staff at that very welcoming institution, who were so helpful and a great pleasure to work with. Special thanks to Dave Orwig, Emery Boose, Audrey Barker Plotkin, Elaine Doughty, Julie Pallant, John OKeefe, Clarisse Hart, Scot Wiinikka, Edythe Ellin, and Laurie Chiasson. Brian Hall stepped up with his considerable mapping skills and created the illustrations that help explain the meteorology. David Foster, Harvard Forests director, deserves superlatives in many regards: inspiring teacher and leader, prolific writer, and highly influential figure in the world of ecology and conservation, he still always found time to help me understand the nuances of natural and human disturbance. He has opened many doors for me, and for that, I am indeed grateful.

I thank Bob Saul, whose encouragement, enthusiasm for this project, and generosity made it possible for me to set aside the time I needed to complete the writing.

I am indebted to the many people who told me their stories of living through the Great New England Hurricane, especially Harry and Joan Brainerd, Dustin and Jane White, Fred Hunt, Bryce Metcalf, Lois Sherwood, Jim Colby, Allen Britton, Tink and Polly Hood, Fred Spooner, Harold Luce, John Hemenway, and Put Blodgett. My gratitude to Fred Hunt, Jim Colby, Harry Brainerd, and Harold Luce is tempered with sadness; they were instrumental in helping me understand the terror of the storm and have passed away before they could hold this book in their hands.

Some other people you will meet in the book have been enormously generous with their time, particularly Charlie Cogbill and Lourdes Aviles, who put up with an endless stream of follow-up questions, and local weatherman Mark Breen, who gave me a crash course in meteorology.

Next page