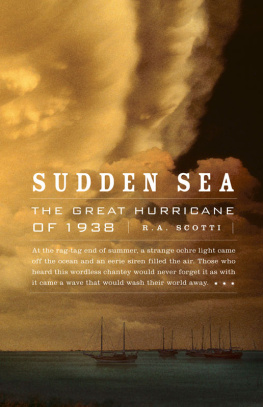

The Great Hurricane: 1938

The Great Hurricane: 1938

CHERIE BURNS

Copyright 2005 by Cherie Burns

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, or the facilitation thereof, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Any members of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or publishers who would like to obtain permission to include the work in an anthology, should send their inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Burns, Cherie.

The great hurricane1938 / Cherie Burns.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

eBook ISBN-13: 978-1-5558-4614-5

1. HurricanesNew York (State)Long IslandHistory20th century. 2. Long Island (N.Y.)History20th century. 3. Long Island (N.Y.)Biography. I. Title.

F127.L8B93 2005

974.7'21043dc22 2005041211

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

for Dick, Alex, and Jessie

Confronting a storm is like fighting God. All the powers in the universe seem to be against you and in an extraordinary way, your irrelevance is at the same time both humbling and exalting.

Frances Legrande

Introduction

I first heard about the Great Hurricane of 1938 from a friend in Nantucket. She explained that her mother felt anxious when visiting her seaside cottage during rainy weather or when she felt the rhythm of the waves rising through the floorboards on certain summer nights. Her grandmother had been killed in a hurricane in Rhode Island that had swept hundreds of people off the beach, she said. I had never heard of such a thing, especially in New England. I had seen newscasts of the victims of hurricanes in Florida and the Caribbean, but their losses were mainly property since they had always been evacuated well ahead of time.

A few years later I heard again of the Great Hurricane of 1938. I was with a woman from Rhode Island who mentioned that her grandparents had both drowned in the big hurricane in Rhode Island. By then I had seen for myself what a hurricane can do. I was in Nantucket in August 1991 when Hurricane Bob hit the East Coast. I got a firsthand look at the damage I had seen before only on television. No lives were lost in Nantucket that year, but fallen trees made the streets of our village impassable. Power and water were knocked out for several days, and in its wake was a bitter parching of all the summer foliage. The 110-mile-per-hour winds and salt spray stripped all the trees or turned them brown overnight. Summer ended in a day. Some deciduous trees never recovered. As I drove into Nantucket town the morning after, I saw the masts of sailboats in the harbor tilted at a sickening 45 degrees. Another boat had been driven into a restaurant. The clear sky and winking bright sun sparkled in the moisture still trapped in the air, like a sly wink after some act of treachery. It took weeks to clean and repair the damage.

That same fall another storm came to Nantucket. The October 11 storm, which would become known as the infamous perfect storm, wreaked much more damage on both Long Island and Nantucket. The local Nantucket newspaper made a video I watched later on Thanksgiving. No footage had ever affected me as did that black-and-white tape of two middle-aged sisters hurrying to remove what they could from their seaside house, just down the bluff from ours, before the waves claimed it. Then came the worst. In an eerily silent scene, the house rode slowly out to sea on the waves. For several moments it swayed and drifted like a houseboat, and then the vertical white trim along the roof and sides collapsed like Popsicle sticks. A final surge of waves with whitecapped spray rose and the house was gone, swallowed whole by the sea.

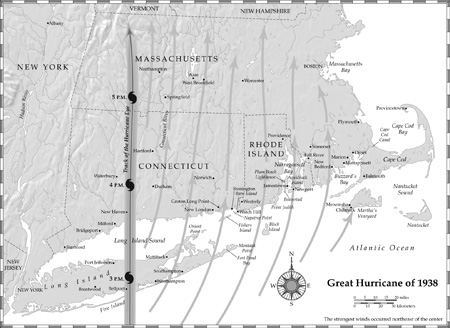

Soon after, I read about the Great Hurricane of 1938 in The Perfect Storm. In making his point that a mature hurricane is the most powerful event on earth, author Sebastian Junger mentioned that in the Hurricane of 1938, the waves shook the earth so hard that they were registered by a seismograph five thousand miles away in Alaska. The perfect storm that swept away the crew of the Andrea Gail in the Grand Banks of the Atlantic was of considerably lesser magnitude than the 1938 hurricane. The Great Hurricane of 1938 seems to have earned a little-known place in the annals of sea history despite its wider anonymity. When later I spoke with a friend, an excellent sailor, who talked about sailboat racing off the spit of sand that is now Napatree Point, I told him the point was once lined with gracious summer cottages and that children in woolen swimsuits played in the surf in front of the houses off Fort Road. I could see that he didnt believe me.

Why, I began to wonder, was this legendary hurricane not better known? Except for the above references, televised anniversary specials during hurricane season, and a few books compiled from newspaper accounts and historical collections, the Great Hurricane of 1938 had been largely forgotten. Yet everyone I asked who had lived through it knew about the tragedy. To them it was a milestone event like Kennedys assassination, Pearl Harbor day, or even September 11. The answer lay partly in history. The day after the hurricane, Hitlers troops moved into Czechoslovakia and the news media were mesmerized by the emerging specter of World War II. As a result, the Great Hurricane came and ripped its way from Long Island to Providence without the nation ever comprehending the enormity of the disaster.

Even when predicted, hurricanes are experiences no one forgets. I recently spent an evening with a woman from St. Thomas who tried to explain to me the sensation of pressure bearing down on her head that accompanied the hurricane she had experienced in the tropics in 1995. She talked of her roof buckling, of watching furniture blow out the door of her house, and of the shattering sound of breaking glass and splintering trees and furniture as clearly as if theyd happened yesterday. The hurricane winds sounded like the roar of a speeding freight train, she recalled. It was the same description Id heard from the survivors of the Great Hurricane. This woman also spoke of the post-traumatic depression survivors experienced, and I made note that not one of the nearly fifty survivors I interviewed for this book spoke of depression or flagging mental health following the Great Hurricane of 1938.

In reporting this book, I have come to believe that, sixty-five years after a disaster, people have forgotten the emotional trauma that came in its wake. They focus instead on the drama of the event, and it is the active elements of the disaster that fascinated them then and now. Thats what seems to lodge in memory. Back then people didnt talk a lot about how they felt, perhaps because they didnt have the luxury of doing so with the Depression at their backs and the outbreak of another world war ahead. In 1938 people seemed to get on with life, no matter how dismal the prospect.

I was also amazed at the way memory plays tricks with people in extreme circumstances. The experience of a disaster is clearly so intense that it seems to bend the laws of physics and make people believe they witnessed impossible events. I heard of a car being picked up by the wind and hurled into a pond like a toy and of a little boy blown up into the air like someone in a Harry Potter story until his nanny, in the nick of time, grabbed him by the foot and yanked him back to earth. The ferocious experience of the hurricane was so far outside the normal boundaries of routine occurences that many people believe things happened that clearly didnt, or were exaggerations of the real events.

Next page