Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

Copyright 2014 by Kathryn Miles

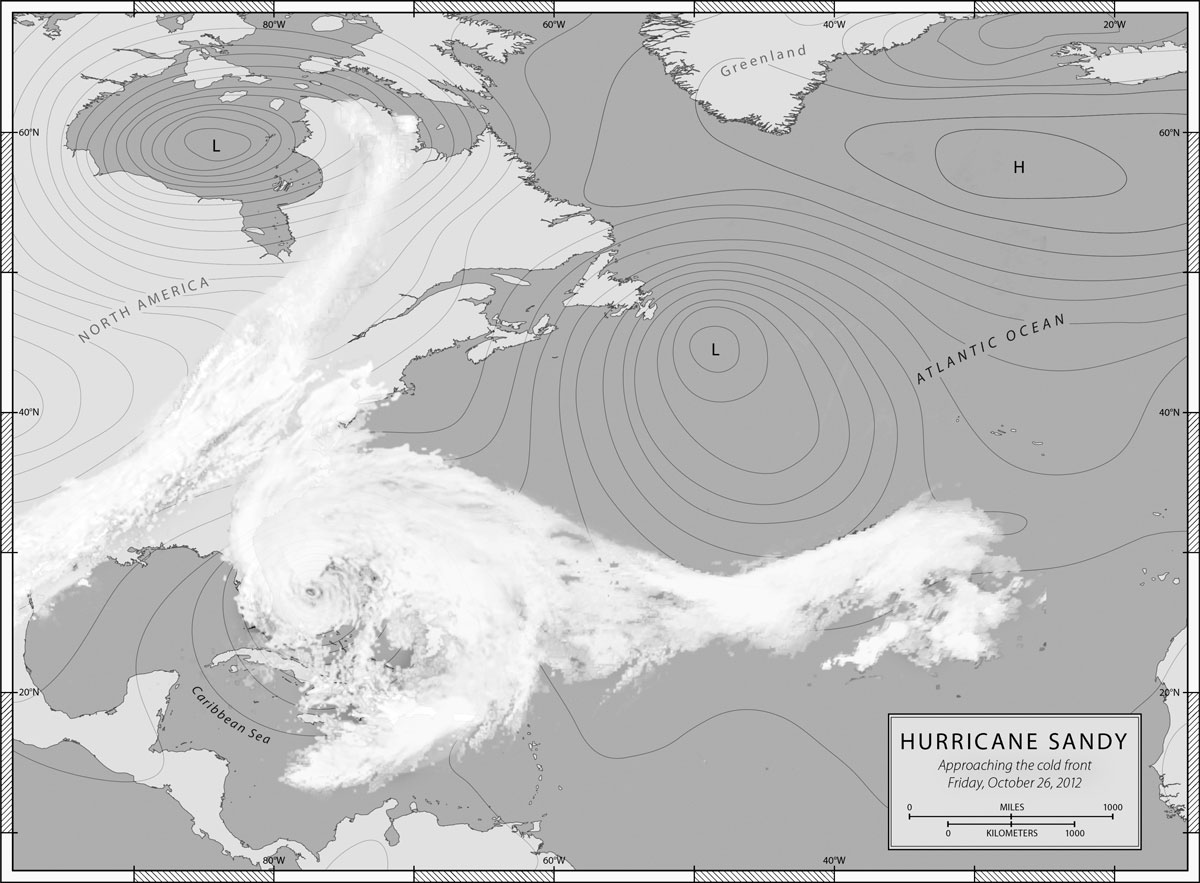

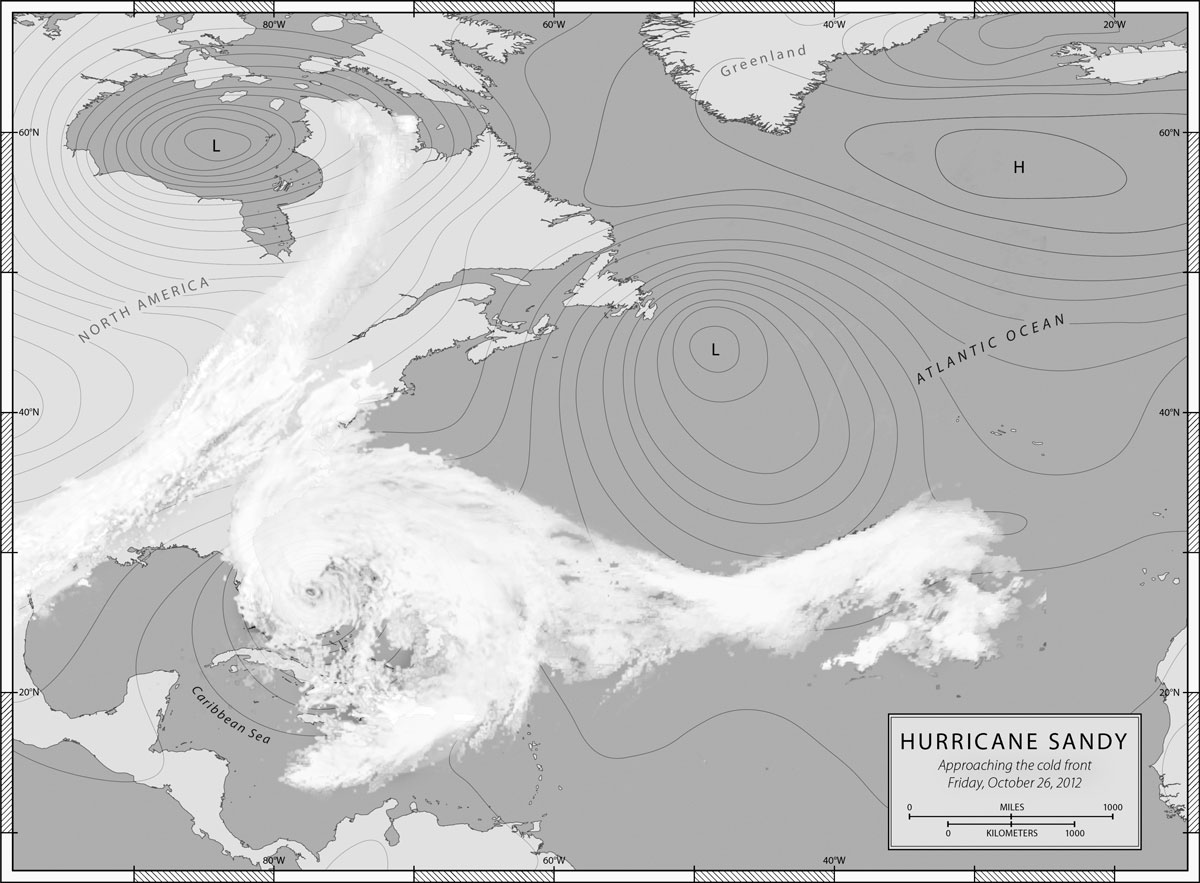

Endpaper map copyright 2014 by Margot Carpenter/Hartdale Maps

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

DUTTONEST. 1852 and DUTTON are registered trademarks of Penguin Group (USA) LLC

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Miles, Kathryn, 1974 author.

Superstorm : nine days inside Hurricane Sandy / Kathryn Miles.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-698-18622-4

1. Hurricane Sandy, 2012. 2. HurricanesUnited StatesHistory21st century. 3. Weather broadcastingUnited States. I. Title.

QC945.M46 2014

551.55'2dc23 2014031087

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Version_1

For Hayden,

who helped write the first word

In the eye of a hurricane, you learn things other than of a scientific nature. You feel the puniness of man and his works. If a true definition of humility is ever written, it might well be written in the eye of the hurricane.

Edward R. Murrow

CONTENTS

LANDFALL

T HE SKY WAS lit by a full moon that night, but no one could see it. Everythingthe enormous harvest moon, the stars, the horizonhad been consumed by cloud. The storm was so immense it caught the attention of scientists on the International Space Station, who stopped what they were doing and peered out their windows. From there, the cloud cover seemed almost limitless: 1.8 million square feet of tightly coiled bands so huge they filled the windows of the station, so thick they showed only the briefest insinuation of an eye. It was the largest storm the planet had ever seena storm big enough to consume the entire Eastern Seaboard and beyond.

It had already wreaked devastation in the Caribbean, taking lives and destroying families. Now the storm was marching up the Atlantic, turning the ocean into unimaginable chaos. Waves the size of a two-story house collided against one another, exploding in foam and fury and blocking everything else from view as millions of pounds of water rose and crashed and fell, only to rise again. Those same waves fueled the machine that created them, sending more and more moisture into the storms core, where energy exploded with the force of a nuclear bomb. Gale-force winds rose and then spread out for 870 nautical miles, threatening everything in their path. The system was growing.

Nightfall came by imperceptible degrees. The wind and rain did not. They were soon punctuated by an omnipresent moaning: a kind of dark, low hum that made it seem as if the entire world was haunted. Within minutes, that moan became a constant, pervasive shriek as gusts of 90 miles per hour were recorded everywhere from Washington, D.C., to New York City. Barometers plummeted to unseen lows, heralding the force of the storm. So, too, did the apocalyptic precipitation that began to follow: almost thirteen inches of rain in Bellevue, Maryland; nearly six in Cleveland, Ohio. Twenty inches of snow fell in places like Kentucky and Newfound Gap, a low pass in the Great Smoky Mountains that divides North Carolina and Tennessee. In West Virginia, more than three feet of snow fell near the town of Richwood, collapsing roofs and collecting into barricade-like drifts six feet tall.

At the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., keepers scrambled to corral their charges inside, wrangling elephants and clouded leopards, the facilitys iconic pandas, and even a spindly, two-week-old dama gazelle. As they did, the storm turned inland, fixing a bead on the mid-Atlantic coast. Heralded by hurricane-force winds, the storm announced its arrival long before it made landfall, knocking down power lines and exploding transformers. A woman in Toronto was killed when a large illuminated sign pulled from its supports, then plummeted thirty feet to the ground. An eight-year-old Pennsylvania boy died when a tree fell in his Franklin Township yard. Not long after, an enormous oak fell through a home in North Salem, New York, crushing two best friends, ages eleven and thirteen, but leaving the rest of the homes occupants unharmed.

And still the storm continued its relentless beat to shore, charging across three hundred miles of open ocean, picking up strength with every step. Meteorologists and scientists, officials and emergency managers stood baffled: What was this thing? By the time many of them decided, it was too late to issue warnings, too late to persuade millions of people their lives were in danger.

Gusts rose to 83 knots, building the waves higher, blowing off their tops and sending cataracts of salt water through the air for miles. Across Manhattan, those residents who resisted the call to evacuate struggled to walk down rain-swept streets, where litter tornadoed around telephone poles and newspaper kiosks. Awnings sheared off of storefronts and took flight. Flags stood straight and solid; trees rippled as if suddenly liquefied. Nearly a thousand miles away, spray from twenty-foot surf on Lake Michigan crashed onto Chicago museum-goers and commuters. At the international airport in Gary, Indiana, 50-mile-per-hour winds grounded planes. Hundreds of stranded passengers sat packed in terminals from Baltimore to Oklahoma Cityand beyond.

By 6:00 P.M. that evening, three million people were without power, most of them in Manhattan and the surrounding boroughs. The lights went out on Broadway. Wall Street ground to a standstill and would remain closed for two daysthe first time weather had shut down stock markets for consecutive days since the Great Blizzard of 1888. Out on Ellis Island, the Statue of Libertywhose newly renovated crown had reopened to visitors just one day beforelost her torchlight and went dark.

At New York Universitys Langone Medical Center, hospital officials were certain their patients would be safe, despite the deteriorating conditions outside. But the facilitys backup power system soon failed, shrouding the eighteen-story complex in blackness and requiring the evacuation of three hundred patients into a caravan of ambulances that extended blocks down rain-torn streets. The first to emerge from the darkened hospital were twenty infants from the neonatal intensive care unit, each one cocooned in blankets and heating pads and carried down nine flights of stairs by nurses, administrators, and maintenance workers. They worked by flashlight and feel, delivering first the babies and then the most critical patients, some of whom weighed well over two hundred pounds. They moved silently, synchronized, and often arm in arm, working together in teams of five or ten and stopping frequently to check breathing tubes and vitals. The only audible sound, some would report later, was that of the growing wind and surf. Waves so big they hardly seemed real rolled through streets. It was like being in a movie, said the staff, only much, much scarier.