Contents

Landmarks

Page List

Trailed

One Womans Quest to Solve the Shenandoah Murders

Kathryn Miles

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL 2022

For Camille and Suzanne,

who saw us through

CONTENTS

Border Woman

Walls her own lands

With her own soul

In communion

With her own spirits

Between two lands is where my heart is.

The land is not mine any less than

It is yours.

I am me you are you. And we are we.

Stop and listen.

Flow and ebb with me.

I bleed. I breathe. I live.

Julie Williams , journal entry

December 12, 1995

Authors Note

Trailed is based on four years of reporting, which includes reviewing court transcripts and motions, archival news stories, and scholarship, along with the authors interviews with over a hundred sources. All dialogue rendered in direct quotations was either independently verified or recorded. Dialogue in italics has either been paraphrased for the sake of clarity or because it is based on a persons recollection and cannot be independently corroborated. Whenever possible, I have used the full names of individuals. In some cases, where people have reasonable expectations of privacy, I have opted to identify them only by their first names. In a few cases, people have asked to remain anonymous because of safety concerns or fears of reprisal. In those cases, I have changed their first names. These changes include the name of my partner at the time, who has asked to be referred to by his nickname, Ray.

This book includes multiple references to violence, including sexual assault and murder, that some readers may find upsetting or otherwise triggering. Every effort has been made to approach these subjects with sensitivity and respect.

Preface

They must have been followed. Thats the thought I return to after all these years.

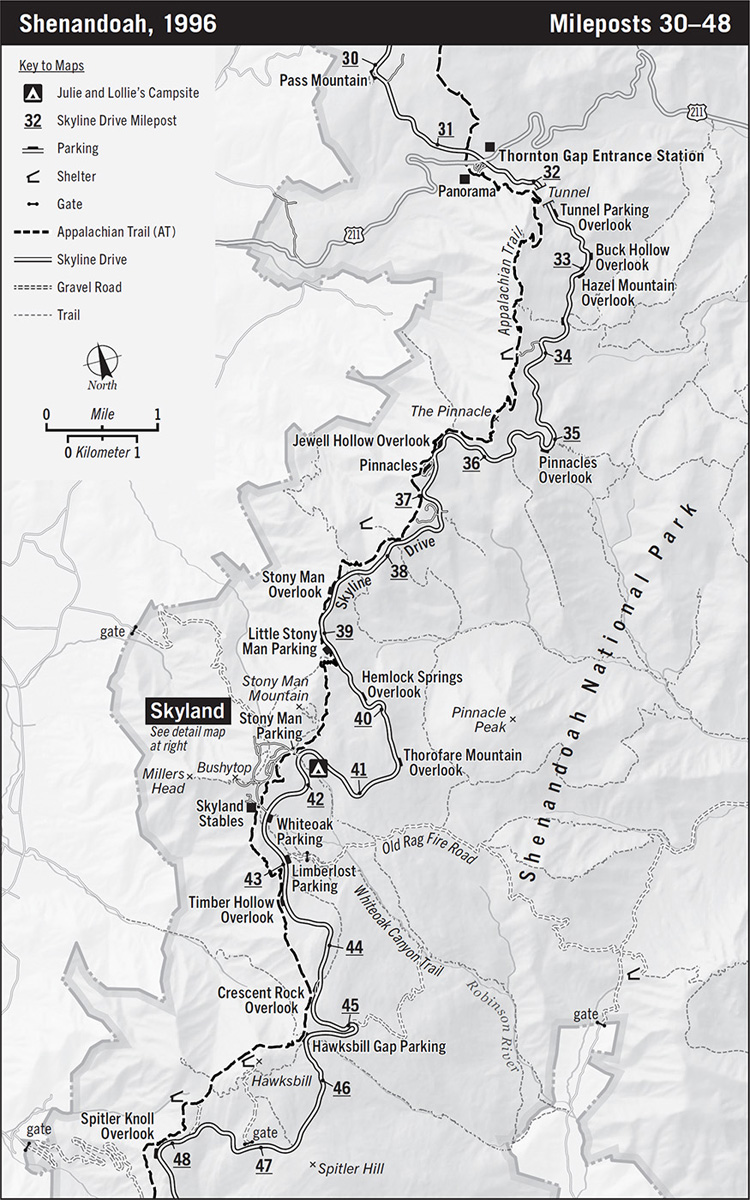

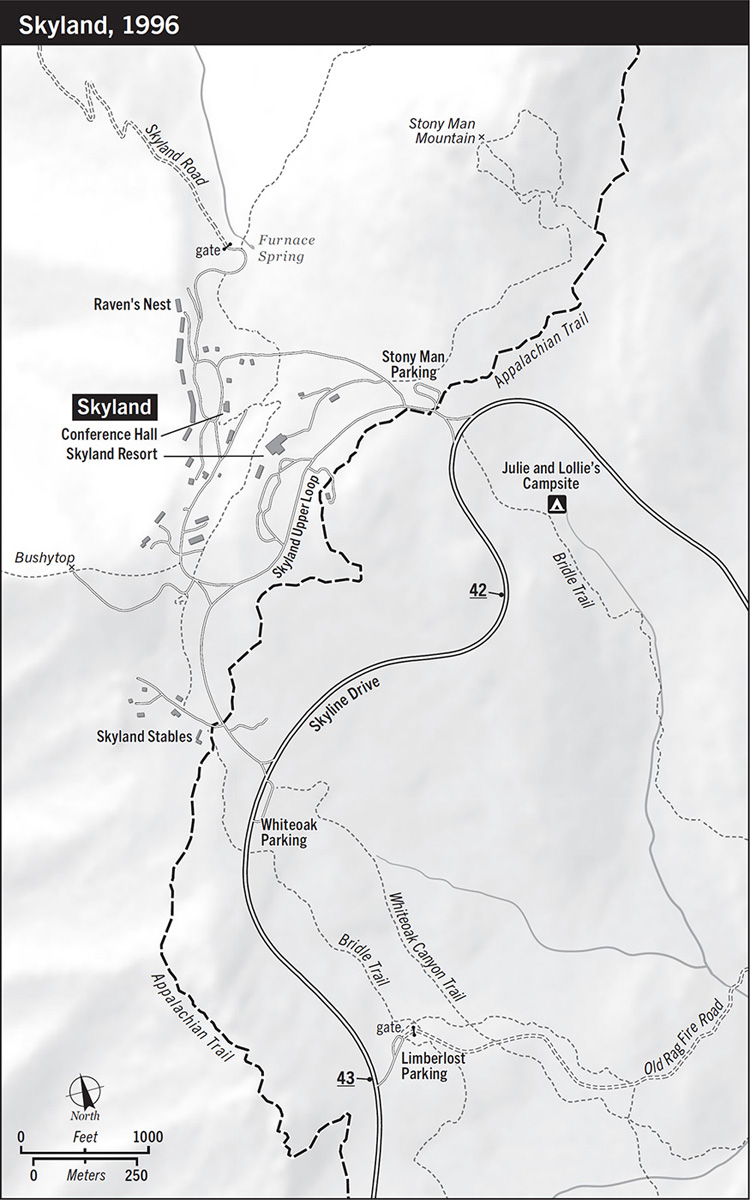

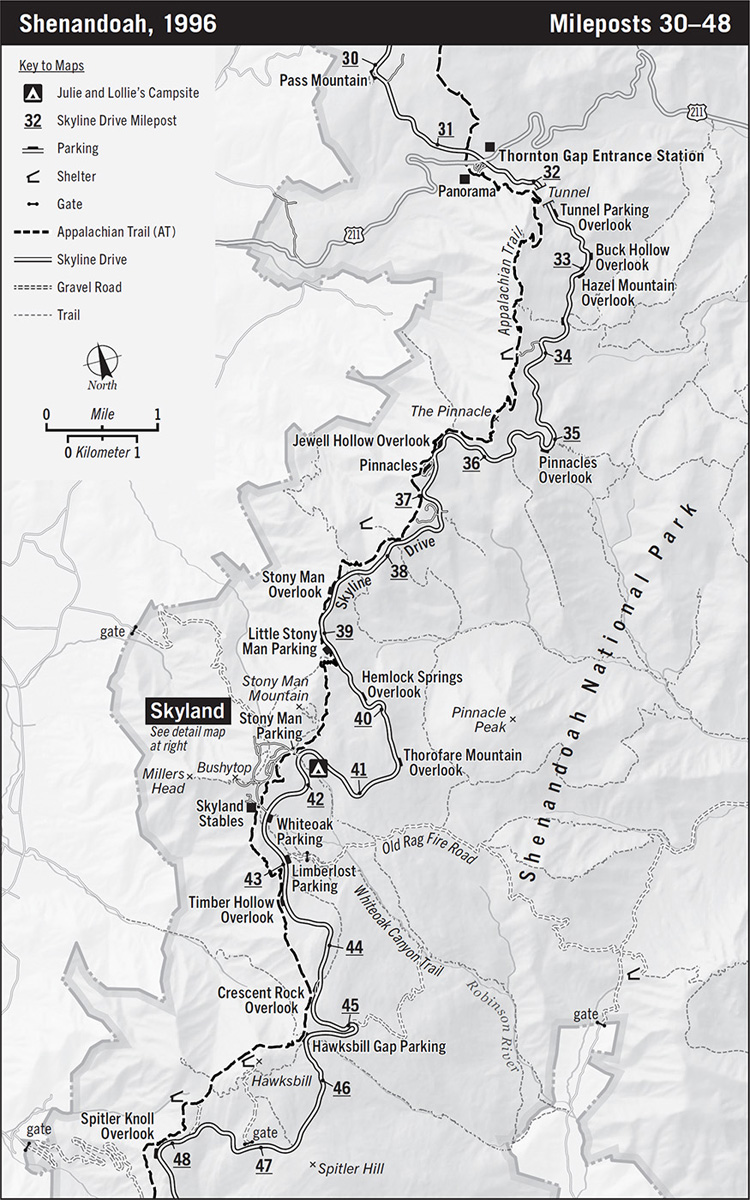

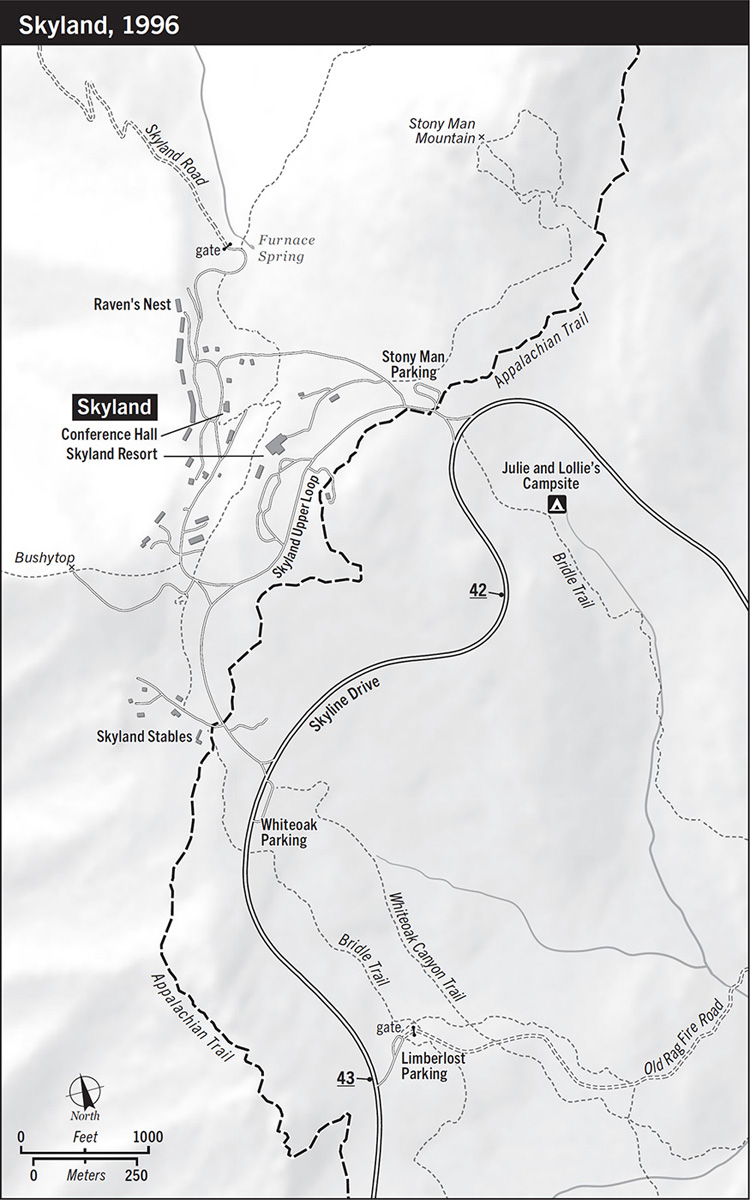

They must have been tracked as they left the Skyland lodge and stepped across Skyline Drive, the well-traveled backbone of Virginias Shenandoah National Park. Hefor murderers are almost always hesmust have been prowling Skylands parking lots and public areas, hoping hed find the right target. Perhaps he studied the two young women as they lounged in the grass outside the lodge, oblivious as they consulted a map or warmed themselves in the afternoon sun. Maybe he bumped into one of them as she was leaving the restroom or grabbing a drink in the taproom. Something about their countenance and mannerisms must have caught his eye, made him decide hed found what he had been hunting for.

He was calculating and confident. He would have thought little about following the women as they left the lodge area and descended that lonely, overgrown path. He must have felt emboldened once he realized how easy it was to hide there. Spring had come early to the Shenandoah Valley. Up near the lodge, grass had already become meadow: blades waved high and were bowed over by seed; wildflowers stood in ostentatious clumps. Along the Bridle Trail, the gnarled stems of mountain laurel and rhododendron had erupted in glossy, deep leaves, creating a sea of dark shadows. Towering above them, a canopy of wizened hickories and chestnut oaks made the corridor feel close and tight, blocking everything but the immediate present from view. The foliage was so thick, in fact, that days later searchers looking for the women would repeatedly walk past their hidden campsite without even noticing their brightly colored tent.

But not him.

He must have hung close, stalking them as they turned off the trail and bushwhacked back to their campsite. The roar of the nearby stream would have masked the sound of his footfall as he drew near. And even if the women had time to scream, he knew no one else could hear them.

Julianne Julie Williams and Laura Lollie Winans were skilled backcountry leaders. By May 1996, theyd each led dozens of trips: orchestrating ten-day expeditions in unforgiving landscapes like Minnesotas Boundary Waters and New Hampshires White Mountains and taking inner-city women and their children on their first camping experiences in urban parks and recreation areas. Just one semester separated Lollie, age twenty-six, from a college degree in outdoor leadership at Unity College in Maine. She was confident, egoless, and a unique combination of gregarious and fiercely protective: always glad to meet you but also cautious to trust. Julie, twenty-four, had already traveled the world, volunteering in hardscrabble communities in South America, sifting through archaeological sites in Greece and Italy, surveying some of our most remote wilderness areas. She was quiet, big hearted, self-assured.

Theyd met the previous spring while working at a world-renowned outdoor program for women. Theyd also fallen in love there. But this was 1996: the same era when the US Supreme Court determined that antisodomy laws did not violate the Constitution and when voters in Colorado approved measures to declare homosexuality abnormal and perverse. It was also two years before Matthew Shepard was beaten and left to die in a coarse prairie field dotted with sagebrush and a year after the Olympic diver Greg Louganis sparked panic in public pools across the country after announcing he was both gay and HIV-positive.

Julie and Lollie were all too aware of the repressive zeitgeist of that time. And so that new, crazy love they felt was also something they kept almost entirely private. Out in the world, they traveled as good friendsjust two young women who happened to share a passion for wild places.

That passion was what had taken them down Shenandoah National Parks Skyland Meadows Bridle Trail in May 1996. Located just two hours from our nations capital, Shenandoah National Park feels a lot more remote. On a map, its 196,000 acres of forest look like a lizard sprawled along the narrow ridge of Virginias Shenandoah mountains. Slicing through the middle of this long stretch of green is Skyline Drivethe only significant paved road in the park. During the height of the summer season, Skyline Drive is thronged with visitors, who flock to its postcard-perfect overlooks, resorts, and picnic areas. But get a mile beyond the drive on either side, and the park can seem as wild as any remote western landscape.

Decades earlier, the Bridle Trail had been well used: a thoroughfare for the nearby Skyland resorts stables, a place where parades of families were led on trail rides day after day. In time, stable managers decided crossing busy Skyline Drive was too dangerous for novice riders, so they relocated their horse trail behind the resort complex. In the years following, Virginias abounding foliagefirst serviceberry and interrupting ferns, then tickseed, wild blackberries, and poplar shootsbegan to overtake the path. The trail slipped off park maps entirely. By the time Julie and Lollie arrived, all that remained was an unimpressive concrete marker on the edge of the parks main road. No bigger than a Civil War gravestone, it floated half-submerged in a tangle of grass and weeds.

Despite the overgrown terrain and lack of obvious markers, Lollie and Julie somehow found their way to the hidden Bridle Trail trailhead. Weighed down by overstuffed backpacks, they slowly descended eastward. A quarter mile down the steep path, they, along with Lollies golden retriever mix, Taj, turned left and bushwhacked two hundred yards through the understory. There, they reached the northern fork of the Whiteoak Canyon Stream. The women set up their tent, stacked their heavy packs one upon another. They hung their water purifier; draped the tents blue-and-yellow rainfly and staked it to the ground. They were so far hidden even the bright nylon of that rainfly would have seemed barely a whisper through all the early-season growth: maybe a resting goldfinch or jay, if you noticed it at all.