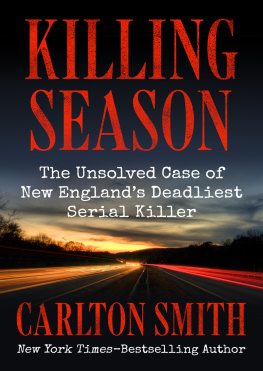

Killing Season

The Unsolved Case of New Englands Deadliest Serial Killer

Carlton Smith

Contents

For Judy, Jill, and Jolene

Major Characters

The Police

Ronald Pina, Bristol County District Attorney, 19781990

Raymond Veary, Ron Pinas chief deputy

Robert St. Jean, chief investigator for Ron Pina

Paul Boudreau, detective, Bristol County Drug Task Force

John Dextradeur, detective, New Bedford Police Department

Jose Gonsalves, corporal, Massachusetts State Police, lead homicide investigator in the Highway Murders

Maryann Dill, trooper, Massachusetts State Police, and Gonsalvess partner

The Victims

Robin Rhodes, 28, last seen in New Bedford, April 1988

Rochelle Clifford Dopierala, 28, last seen in New Bedford, late April 1988

Debroh McConnell, 25, last seen in New Bedford, May 1988

Debra Medeiros, 30, last seen in New Bedford, late May 1988

Christine Monteiro, 19, last seen in New Bedford, late May 1988

Marilyn Roberts, 34, last seen in New Bedford, June 1988

Nancy Paiva, 36, last seen in New Bedford, July 7, 1988

Deborah DeMello, 35, last seen in New Bedford, July 11, 1988

Mary Rose Santos, 26, last seen in New Bedford, July 16, 1988

Sandra Botelho, 24, last seen in New Bedford, August 11, 1988

Dawn Mendes, 25, last seen in New Bedford, September 4, 1988

The Families

Judy DeSantos, sister of Nancy Paiva

Joseph Botelho, father of Sandra Botelho

Diane Clifford, mother of Rochelle Clifford

James McConnell, father of Debroh McConnell

Charlotte Mendes, mother of Dawn Mendes

Madeleine Perry, mother of Deborah Greenlaw DeMello

Donald Santos, husband of Mary Rose Santos

The Suspects

Neil Anderson, Dartmouth, Mass., fishcutter, cleared January 1989

James Baker, Tiverton, R.I., diesel mechanic, cleared, June 1989

Tony DeGrazia, Freetown, Mass., stonemason, cleared, October 1989

Kenneth Ponte, New Bedford, Mass., attorney, cleared, August 1991

Paul Ryley, New Bedford, Mass., businessman, cleared, August 1991

The Others

Frankie Pina, Nancy Paivas boyfriend

Henry Carreiro, radio talk-show host

James Ragsdale, editor, New Bedford Standard-Times

Maureen Boyle, reporter, New Bedford Standard-Times

Tom Coakley and John Ellement, reporters, The Boston Globe

Diane Doherty, witness against Kenneth Ponte

Paul Walsh, Ron Pinas election opponent in 1990

Paul Buckley, special prosecutor appointed by Walsh to review the case, 1991

Preface and Acknowledgments

Such dreary streets, Melville had written in 1850 of New Bedford, Massachusetts, at the height of the citys century-long, whale-killing bonanza. Though nearly 140 years had passed since the time of Melville, and the whales were long gone, the streets of New Bedford remained dreary in the late 1980s, lost in a gloom that seemed as permanent a part of the city as its bumpy cobblestones.

In the town once made rich by oil from the largest mammal in the history of the world, there seemed to be as many cobblestones and historic buildings as there were tenements; and there were almost as many tenements as there were addictsthat is, drug addicts. The harpoon, at least, had survived, miniaturized perhaps, but still firmly lodged in the forearms of the unhappy, trapped people of what was once the richest city in the world.

A pedestrian on Purchase Street in the spring of 1988 could not avoid the evidenceindeed, it was loudly whispered, spoken, sometimes even shouted, advertised by sidewalk pitchmen called runners, or sometimes clockers:

Power, Power Ninety-five, Master of Deaththese were the street names of the small packets of white or brown powder dispensed by shadowy figures down on Purchase Street in New Bedford in the spring of 1988. Crumpled, sweaty bills changed hands; a darkened space was sought, a spoon produced, a match was lit, a needle was filled and plunged.

Then came the explosion, or rather, implosion, as a human life shrank down to its lowest conscious level, a full retreat from the things that could no longer be suffered. And not just a few, either.

By the spring of 1988, nearly 1 out of 50 New Bedford citizens was an acknowledged heroin addict, while an equal or larger number were addicted to cocaine or its compulsive cousin, crack. It was not surprising that New Bedford, once known as the whaling capital of the world, was now known as one of the worlds biggest drug dens.

The new harpoon, the hypodermic, led directly to real-people crimepetty thefts, burglaries, muggings, shootings, indeed, untold wreckage in human lives. In time those crimes led to serial murder, and the destruction of the soul of a city.

There are three main highways into and out of New Bedford. Interstate 195 runs east from Providence, Rhode Island, slices through the northern half of New Bedford, then heads farther east in the direction of Cape Cod before fading out in a merger with another interstate headed south out of Boston.

A second freeway, State Route 140, heads north out of New Bedford on its way to Taunton, Mass., where it too joins another road to Boston. A third highway, U.S. 6, also known as the Kings Highway, once linked all of southeastern Massachusetts to Cape Cod and Boston, back in the days when coachmen drove with whips. All three of these roads figured prominently in the serial murder case with which this book is concerned.

I first came to New Bedford in the spring of 1989, when the hunt for an unknown murderer was in full cry. Nine women were dead and two others had disappeared. The newspapers and television stations were saturated with coverage about the crimes, and most of all, the suspects. A special grand jury was in session, taking secret testimony.

One man had just been charged with the rapes of nearly a dozen women, and one of those women went on national television to accuse the rapist of being the murderer. The district attorney, Ronald Pina, gave a smug and knowing press briefing on the steps of the county courthouse, saying nothing of consequence but with winks and smirks suggesting broadly that the case was almost solved.

I came back in 1992 and again the following year. Ronald Pina was no longer district attorney, one suspect was dead, anothers life in tatters, a key witness had died on the street, and the nine murders were still unsolved. The two missing women were still missing. But by that time, the killings were a thing of the past for most of New Bedford, a dark event receding into the shadows of the willfully forgotten. The crimes had started, were stopped after they were discovered, and then galvanized the city, and were then ignored as an aberration that somehow could never be explained, just as a controversial pool table rape case had convulsed the town a few years earlier. But the residue of bitterness lingered on.

Why hadnt the case been solved? There was an ample amount of physical evidence; the pool of potential victims was relatively small, and quite close-knit; indeed, the victims even seemed to be closely interconnected, some living together, others living next door to one another, or having, at one time or another, been coworkers or close acquaintances.

The answer, as I hope this book demonstrates, was not so much an absence of evidence, but rather the result of an inability of police and political officials to set aside their own personal agendas and instead focus methodically on the facts. Manipulation of the news media became commonplace, while the media themselves failed to ask critical questions at critical times. The case gradually became a political mess, and eventually the investigation was torn apart in the maelstrom of competing interests. A Federal Bureau of Investigation expert who was familiar with some of the details of the case minced no words when he shook his head sorrowfully and offered his opinion that the investigation had been destroyed by a toxic combination of arrogance and ineptitude.