Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To theBOUNTYcrew and Catalina and Vanessa Smith

THURSDAY AFTERNOON, OCTOBER 25

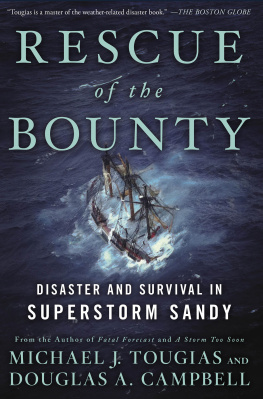

The autumn afternoon was perfect on the New London, Connecticut, waterfront. The rippled river water sparkled; the blue above as clear as freshly washed laundry.

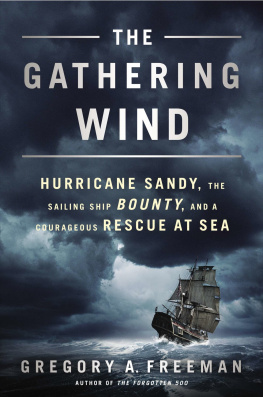

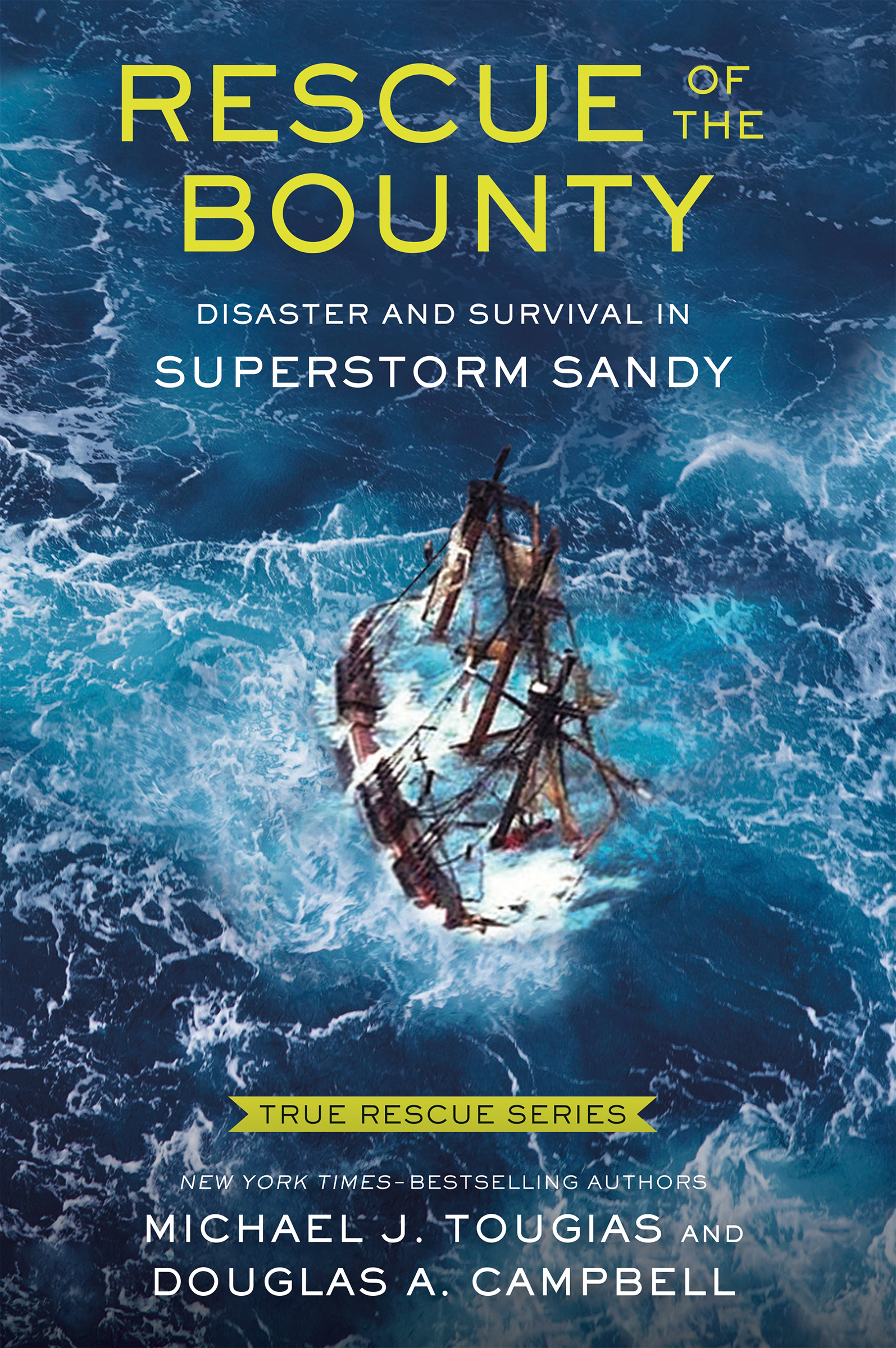

At the dock, a ship named Bounty, with three towering masts and a black hull, floated serenely in the sunshine. Standing on the ships deck was its captain, Robin Walbridge, a quiet, confident man. Although the captain was relaxed, the day had been fraught with more than a little tension.

The fifteen crew members who served under the captain had received anxious text messages or phone calls from family and friends. They knew the 180-foot, 50-year-old wooden shipan expanded replica of the original, famous 1784 Bounty from Englandwas going to sail south to Florida.

They also knew that a hurricane was brewing in the Bahamas and heading north.

A twenty-five-year-old crewman, Joshua Scornavacchi, had received a text message from his mother in Pennsylvania. She was worried about a hurricane named Sandy. Ill be fine, he replied, adding that Bounty had been through rough weather before.

But other crew members were quite concerned. They had heard that the hurricane had the potential to grow into a monster storm.

The first mate, John Svendsen, forty-one, now in his third season aboard Bounty, had talked earlier in the day with his junior officers. The conversation convinced Svendsen, who had his own misgivings, that he needed to talk with Captain Walbridge. He knew the captain planned to start sailing south that evening despite the oncoming storm. Svendsen wanted to present the captain with options.

Svendsen thought Bounty should stay in New London or perhaps sail north to protected harbors such as New Bedford or Boston. In fact, sailing toward Bermuda, 650 miles to the southeast, might be an option. Almost any direction was better than going due south to Florida.

In addition, Svendsen and some of the other crew members became aware of a problem with the Bountys pumps when they were washing the deck that morning.

There were two hoses, neatly stowed on deck, one to reach forward to the bow, the other that extended to the stern. On the ships third and lowest deck, down a set of stairs and then a ladder, there were two diesel engines. The engines powered electrical generators. Those generators ran the pumps set in the bottom-most part of the ship, called the bilge, that sucked the water out. Ocean water that seeped into the vessel through tiny gaps in its wooden planking collected in the bilge. Without pumps, Bounty would eventually sink, like any leaky wooden boat.

There were pipes and hoses extending from the two pumps to the bilge space below the floorboards of the third deck. Any water that collected in that bilge space was sucked through the hoses and pipes and discharged back into the sea. But the process could be reversed, with seawater sucked up into the deck-washing hoses.

It was this seawater that the team was using to clean the decks that bright autumn morning. One team member noticed something different, troubling. Instead of a powerful stream, the washdown hoses were giving him barely enough spray to wet the deck boards. That meant that the pumps didnt have the proper power. So if water was coming into the ship in bad weather, the pumps wouldnt suck it out fast enough or at the proper strength. He mentioned the problem to his two teammates, who seemed unfazed. Then the worried crewman reported his concerns to the ships engineer. In the end, the pump problem was ignored.

First Mate Svendsen put that problem asidehis focus was on the hurricaneuntil he finally had a chance to talk to Captain Walbridge alone.

There are people concerned about the hurricane, Svendsen told his boss. I want to discuss options, including staying here.

Walbridge listened to his first mate, as he always did, and then he offered his own thoughts. He said he would hold a meeting with the crew and explain his plan.

Walbridge conducted an all-hands meeting at about five oclock. Often, Walbridge used these meetings as teaching opportunities, since he saw his purpose aboard Bounty in part as an educator. In fact, he had come from a family of teachers, as far back as grandparents and some great-grandparents.

This meeting would be different, though. Walbridge, celebrating his sixty-third birthday that afternoon, climbed atop a small deckhouse called the Navigation (Nav) Shack (an enclosed area with a chart table and navigation and communication equipment) and, in his quiet way, began talking.

On this afternoon, he had already come to a decision and selected a path for the ship to travel. Certainly there were alternative routes for Bounty in the days to come. Like the chess player hed been for fifty-five years, the captain had considered all those moves and dismissed them.

There is a hurricane headed this way, he told his fifteen shipmates, the falling sun at his back. Its called Frankenstorm. There will be sixty-knot winds and rough seas. The boats safer being out at sea than being buckled up at a dock somewhere. Then he laughed a little and, as if in jest, added: You guys will probably be safer if you take a train inland. The levity ended there.

If anyone wants to go ashore, now is the time. I wont think any less of you. Come back to Bounty when the weather clears up.

No one budged, nor did anyone speak.

My plan is to sail south by east, to take some time and see what the storm is going to do. He told them about hurricanes Bounty had encountered under his command. The ship had made it through then, and she would do so now.

Still, no one spoke. First Mate Svendsen, who had given his captain his best advice, did not share his earlier concerns. He now accepted the Walbridge plan as prudent.

Nor did the second and third mates or the bosun give voice to their doubts.

Some of the crew members were nervous as they looked up at Walbridge. Some were excited for a new adventure after a summer of largely tranquil voyages. The moment for objections passed. Everyoneeven the new cook, who had first boarded Bounty the night beforewent to work, preparing to set sail.

The sun had slipped behind the railroad terminal just inshore from the city dock, and Dockmaster Barbara Neff saw that Bounty was leaving. She stood for a moment and enjoyed the spectacle: a vessel of ancient proportions departing into the gathering dusk, heading south toward a monster storm.

THURSDAY EVENING, OCTOBER 25

Bounty has departed New London, CT Next Port of Call St. Petersburg, Florida.

Bounty will be sailing due East out to sea before heading South to avoid the brunt of Hurricane Sandy.

Entry onHMS BountyFacebook page, 6:06 p.m., October 25, 2012

Adam Prokosh had been aboard Bounty for most of the last eight months. On the evening of October 25, he watched as the ship passed the redbrick Ledge Light- house and entered the Long Island Sound off the Connecticut coast. Prokosh, twenty-seven, of Seattle, had spent several years on a number of tall ships before he joined the crew of the