ON THE EDGE OF SURVIVAL

Also by Spike Walker

Alaska: Tales of Adventure from the Last Frontier (editor)

Coming Back Alive: The True Story of the Most Harrowing Search and Rescue Mission Ever Attempted on Alaskas High Seas

Nights of Ice: True Stories of Disaster and Survival on Alaskas High Seas

Working on the Edge: Surviving in the Worlds Most

Dangerous Profession: King Crab Fishing on Alaskas High Seas

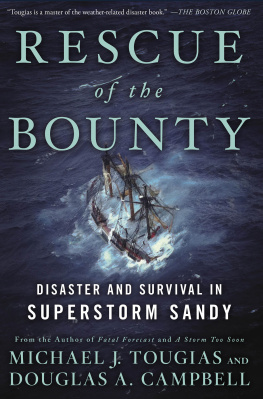

ON THE EDGE OF SURVIVAL

A Shipwreck, a Raging Storm, and the Harrowing Alaskan Rescue That Became a Legend

SPIKE WALKER

St. Martins Press  New York

New York

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ON THE EDGE OF SURVIVAL. Copyright 2010 by Spike Walker. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. For information, address St. Martins Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

www.stmartins.com

ISBN 978-0-312-28634-7

First Edition: October 2010

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Peter and Christina MacDougall, as the Northern Lights danced over Sitka

ON THE EDGE OF SURVIVAL

ONE

Slammed right and left by battering, 60 mph wind gusts, blinded by snow squalls at the leading edge of an Arctic storm, search and rescue pilot Lieutenant David Neel was doing his best, early on that cold December morning in 2004, to shake off the sudden bouts of vertigo and keep his H-60 helicopter on course and in the air. Flying along over the gray and white, foam-streaked waters of the Bering Sea, Neel maintained an altitude of just three hundred feet, and no more, to prevent icing as the tall, clutching storm waves lumbered past below. He and his crew had been ordered to Dutch Harbor, where they would refuel and prepare to launch out on an emerging crisis: The Selendang Ayu, a giant of a freighter, a 738-foot-long cargo ship bound for China with over 60,000 metric tons of Pacific Northwest soybeans, had apparently lost her engine while following the Great Circle route across those same, intractable waters 170 miles northwest of Dutch Harbor. With some 455,000 gallons of bulk oil stored in her tanks, and twenty-six sailors trapped aboard her, the freighter was now drifting on a collision course with the hull-crushing shores of the Aleutian Islands.

If no one was able to alter her freewheeling advance, and efforts either to restart her engine or pass a towline to her failed, the freighter would soon be driven onto the rocks of Unalaska Island inside the largest maritime seabird nesting area in all of North America. Should an oil spill ensuea distinct possibility, given the furious, wind-driven seas now propelling the ship alongthe impact on those vulnerable creatures could be disastrous, the damage to the environment largely irreparable.

The Panamax-class vessel, the largest of the bulk freighters whose hull could still fit through the Panama Canal, was said to be drifting beam-to the pummeling waves. Some of the prodigious breakers slamming into her and driving her toward shore were reportedly as large as freight train boxcars. At times, the wayward vessel was rolling so wildly from side to side, that the six hundred or so feet of her massive deck was tilting almost vertically.

The weather reports, too, were equally alarming. A storm packing blizzard snows with peak wind gusts approaching hurricane force was currently drafting down out of Russias Siberian Arctic. Accelerating as it came, the cold front had marched down over the polar ice pack, and was now racing unhindered across the vast, open reaches of the Bering Sea.

Dave Neel was certain, however, that well before the peak of the storm reached them, he and his crew would be sent to the scene with orders to hoist as many of the sailors as possible off the Selendang Ayus deck before she sank, ran aground, or rolled over. But he also knew that plucking survivors off the heaving deck of a freighter careening through high seas wouldnt be easy; and that doing so in as little time as possible would be absolutely imperative.

Born and raised in Vian, Oklahomaa town of just 1,200 people, surrounded by farmlandDave Neel grew up hunting and fishing, was a fifth-generation Oklahoman, and the son of a bricklayer. His people worked in the construction trade. Dirt moving. Concrete pouring. Home building. His parents raised him and his brothers in a traditional, God-fearing, Baptist belief system, one centered around hard work, honest living, and fair play.

Neel knew the H-60 Jayhawk helicopter well. Hed flown them for years in the army, and also on a tour for the Coast Guard (CG) out of Clearwater, Florida. But the base outside Kodiak was this aviators ultimate destination, a place reserved for the Coast Guards most trusted and experienced pilots. Only second-tour aviators or better were sent there. In fact, famed Alaskan chopper pilot Russ Zullick was one of Dave Neels best friends.

Just twelve hours before, Neel and his crew had been sitting in the cargo hold of a C-130, crossing the Shumagin Islands, when Commander (Cdr.) Bill Deal called him forward into the aircrafts cockpit and told him of the crisis building in the Bering Sea. Their C-130 was being diverted to Cold Bay. An H-60 would be waiting. Neel and his crew needed to start planning the rescue.

Recognizing a true crisis in the making, Coast Guard officials had also ordered the cutter Alex Haley, to the scene. In addition, theyd dispatched several tugboats, including the oceangoing tug Sidney Foss and the harbor tug James Dunlap to try to intercept the drifting giant before it ran aground, scattering fuel, cargo, and bodies along the wild, inhospitable shores of Unalaska Island.

Cdr. Matt Bell, the captain on the Coast Guard cutter Alex Haley, was about 150 miles away, monitoring the actions of a fleet of codfish longliners, when he received word of the errant freighters path and location. Bell and his crew were just winding down from fifty or so days of patroling the westernmost reaches of the Bering Sea along the U.S./Russia border, and were about to stand down and steam back to Kodiak for a well-deserved bit of R & R. But now Bell was ordered to locate the vessel, and to assess the situation.

Riding a quartering sea, and moving in the direction of the freighter with all possible urgency, Cdr. Bell set out in hot pursuit of the freighter. However, because the seas were rough, the Alex Haley could only move at ten knots (11 mph), and it would be a number of hours before they would catch up with the Selendang Ayu. But with half a dozen engineers reportedly among the vessels crew, Cdr. Bell thought the Ayus crew might get their engine back up and running before he even caught sight of her.

Standing six feet tall, and weighing a lean 170 pounds, Cdr. Bell was well suited for the duty at hand. Raised in Georgia by family-oriented parents, he was taught the fundamentals of discipline, work, and academic achievement, a lifestyle that was also accompanied by robust outdoor living.

As a small boy, his first exposure to the sea was while camping and fishing for Spanish mackerel at the waters edge of Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina. During those impressionable years, the Coast Guard bug bit him hard, for he often observed the gleaming white patrol boats cruising the inlets and passageways that wind their way through the beautiful archipelago of islands that make up that seaboard region.

Our summer house was on the inland waterways there, he recalls. You had to take the pass down through all the back bays to get to the jetty before you could get out to the ocean.

New York

New York