For Suzanne, Isabel, and Eve

Contents

T HIS BOOK TELLS two true stories, one from the past and one from the present.

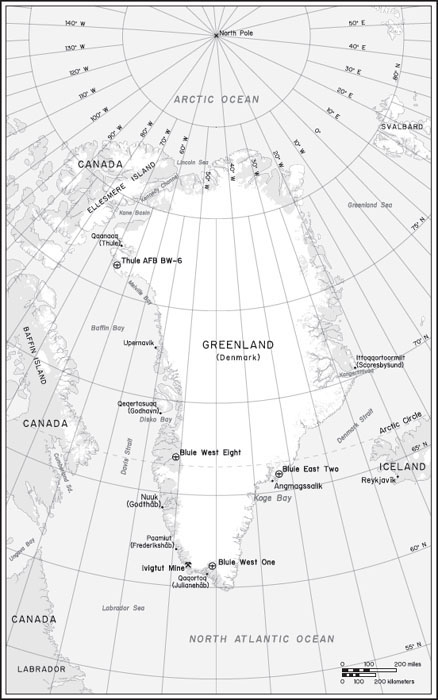

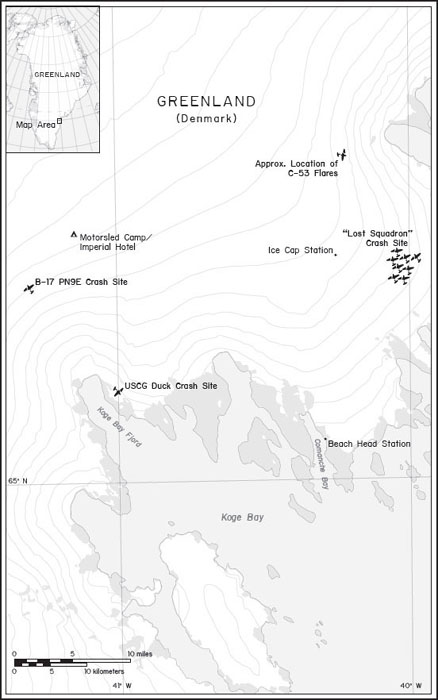

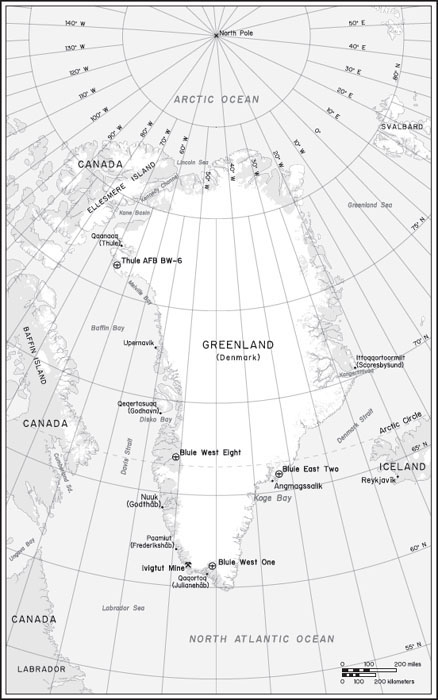

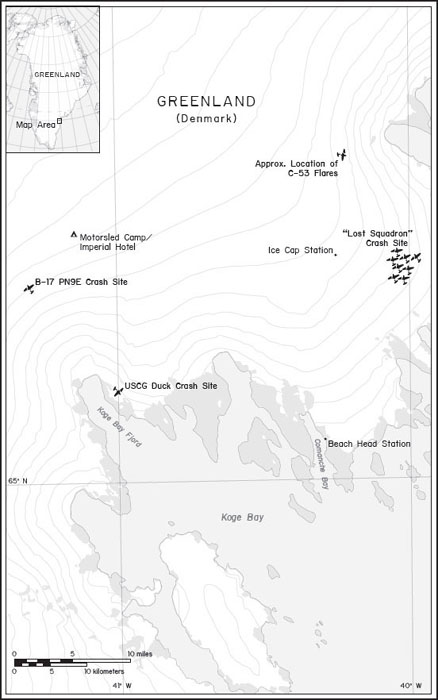

The historic story revolves around three American military planes that crashed in Greenland during World War II. First, a C-53 cargo plane slammed into the islands vast ice cap. All five men aboard survived the crash, and their distress calls triggered an urgent search. Next to go down was one of the search planes, a B-17 bomber, stranding nine more men on the ice. Finally, a Coast Guard rescue plane called a Grumman Duck vanished in a storm with three men aboard while trying to save the B-17 crew.

For nearly five months, through the Arctic winter of 19421943, survivors and their would-be saviors fought to stay alive and sane in the most hostile environment on earth, clinging to life in snow caves and the tail section of the B-17. As the war raged on, Americas military tried to rescue the icebound men by land, sea, and air, sometimes with fatal results. When hope seemed lost, a legendary aviator from the early days of flight devised a half-mad plan to land a seaplane on a glacier.

I learned about these events while hunting through newspaper archives for hidden treasures: stories that once captivated the world, only to fall through the cracks of history. After too many brassiere ads to count, I came across a 1943 series of newspaper articles titled The Long Wait, about the crew of the wrecked B-17. Intrigued, I dug deeper, collecting declassified documents, maps, photographs, interviews, and previously unknown journals, seeking critical mass for a book.

Along the way, I stumbled upon a loose-knit society of men and women determined to locate the Grumman Ducks resting place and to bring home the remains of the three heroes it carried. Driving that effort was a tireless dreamer named Lou Sapienza, a photographer-turned-explorer who dedicated himself physically, financially, and emotionally to finding the frozen tomb of three men he knew only from faded photographs. Through Lou and his cohorts I met families whod been waiting nearly seven decades for the return of their lost loved ones.

I also connected with Duck-devoted Coast Guardsmen who believed that all hands should be present and accounted for, one way or another. One in particular, Commander Jim Blow, committed himself with the same fervor he once gave to his work as a search-and-rescue pilot. Soon I realized that I couldnt tell the full story of the three crashes without also writing about the modern mission of the Duck Hunt.

In the summer of 2012 I joined Lou, Jim, and their combined civilian and military teams on a remote glacier in Greenland, where we experienced the worlds unfinished attic firsthand. Together we used cutting-edge technology, an overlooked military crash report, and a yellowed treasure map complete with an X to solve one of the last mysteries from World War II.

Although written as a narrative, this is a work of nonfiction. As explained in my note on sources, I took no liberties with facts, dialogue, characters, details, or chronology. Because the story moves between past and present, date markers such as November 1942 and October 2011 signal which tale is being told. Also, the historical story is written in past tense, while the modern story is in present tense.

I played a role in the Duck Hunt, and I appear in the book, but it isnt about me. Its about ordinary people thrust by fate or duty into extraordinary circumstances, one group in 1942 and another group seventy years later. Separated by time but connected by character, their bravery, endurance, and sacrifices reveal the power of humanity in inhumane conditions. I hope Ive done them justice.

Mitchell Zuckoff

NOVEMBER 1942

O N T HANKSGIVING D AY 1942, at a secret U.S. Army base on the ice-covered island of Greenland, a telegraph receiver clattered to life: Situation grave. A very sick man. Hurry. The message came from the crew of a crashed B-17 bomber, nine American airmen whose enemy had become the ruthless Arctic.

Two and a half weeks earlier, while searching for a missing cargo plane, the crews Flying Fortress had slammed against a glacier in a blinding storm. Since then, the men had huddled in the bombers broken-off tail section, a cramped cell in a prison of subzero cold, howling winds, and driving snow. Guarding them on all sides were crevasses, deep gashes in the ice that threatened to swallow them whole. Some crevasses were hidden by flimsy ice bridges, each one like a rug thrown over the mouth of a bottomless pit.

One crew member had already fallen through an ice bridge. Another struggled to keep from losing his mind. A third, the very sick man, watched helplessly as his frozen feet shriveled and turned reddish black, the gruesome signature of flesh-killing gangrene.

Their only hope was that someone would answer their distress calls, tapped out in Morse code over a battered transmitter rebuilt by their young radio operator. His frozen fingers curled in pain each time he hit the telegraph key: Dot-dot-dot-dot; dot-dot-dash; dot-dash-dot...

H-u-r-r-y.

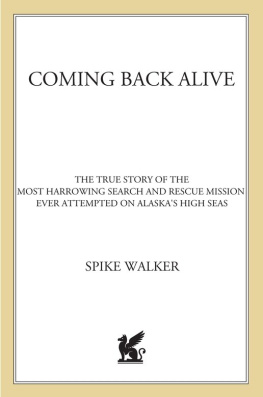

T HREE DAYS LATER, in the predawn darkness of November 29, 1942, John Pritchard Jr. and Benjamin Bottoms lay sleeping in their bunks aboard the U.S. Coast Guard cutter Northland . The ship rocked gently at anchor in an inlet on Greenlands southeastern coast, a place known to the Americans as Comanche Bay. As the United States neared the end of its first year in World War II, the Northland and other ships on the Greenland Patrol kept a lookout for German subs, ferried soldiers and civilians to U.S. bases, and watched for icebergs in shipping lanes.

But when the need arose, they set aside routine jobs for their highest calling: rescue work. They risked their lives and their ships to save sailors lost at sea and airmen whose planes had crashed on the huge, largely uncharted island. Other military branches were Americas swords and spears; the Coast Guard was its shield. John Pritchard and Ben Bottoms embodied that mission as pilot and radioman of the Northland s amphibious plane, a flying boat called a Grumman Duck.

THE U.S. COAST GUARD CUTTER NORTHLAND DURING WORLD WAR II. ITS AMPHIBIOUS PLANE, THE GRUMMAN DUCK, IS FAR RIGHT. (U.S. COAST GUARD PHOTOGRAPH.)

The downed cargo plane that had set the search effort in motion remained lost, each day bringing its five crew members closer to death by cold, starvation, or both. But the nine marooned men of the B-17 bomber crew had been spotted, about thirty miles from Comanche Bay as the Duck flies. The question was how to rescue them from a glacier booby-trapped with crevasses. John Pritchard had an answer. His plan had worked once already, and he intended to put italong with himself, Ben Bottoms, and their Duckto a far greater test this day.

Pritchard and Bottoms scrambled out of their bunks and into their flight suits, insulated shells that discouraged the cold but couldnt defeat it. After a fortifying breakfast, they climbed into the Ducks tight tandem cockpit. Pritchard, twenty-eight years old, an ambitious lieutenant from California, sat up front at the controls. Bottoms, twenty-nine, a skilled radioman first class from Georgia, sat directly behind him. Fur-lined leather helmets sat snug on their buzz-cut heads. Goggles shielded their eyes. Heavy gloves held their hands.

Next page