Contents

For my children

and everyone elses

The ravages of many a forest fire of a bygone age may be read today in the scars left in the tree itself. The exact year that the fire occurred and some idea of its intensity are recorded in the wood, oftentimes grown over with living tissue and hid from the casual observer.

Forest pathologist J. S. Boyce, 1921

Introduction

The Darkness of Ignorance

On October 28, 1886, President Grover Cleveland sailed to a teardrop-shaped island in New York Harbor to formally accept Frances gift of the Statue of Liberty. Under leaden skies and a veil of mist, the president ended his speech with a tribute to the copper-clad ladys torch and her symbolic power: A stream of light shall pierce the darkness of ignorance and mens oppression until Liberty shall enlighten the world.

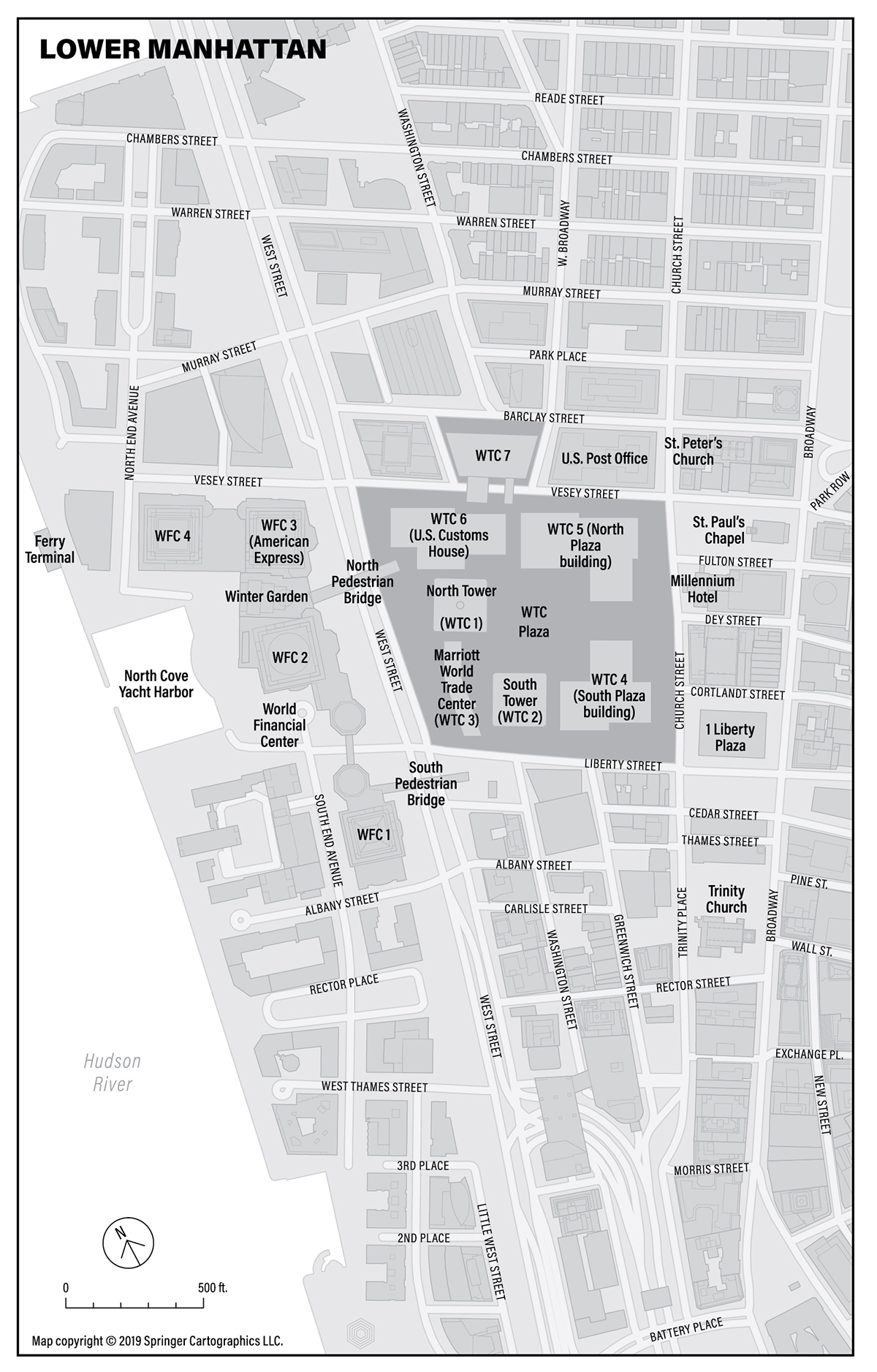

Dignitaries pounded ceremonial last rivets as warship cannons boomed. Across the water in Lower Manhattan, revelers erupted in celebration. Cobblestone streets pulsed with braying horses, throbbing drums, and blooming flower carts. Brass bands marched like front-bound soldiers, and children scrambled up lampposts to avoid being trampled.

Out-of-towners drawn to the spectacle tilted their heads to gawk at the impossibly tall buildings that loomed over them. Amused by these sky-eyed rubes, an office boy in a high tower felt seized by a raffish idea. He opened a window and tossed out long ribbons of the narrow paper tape that normally recorded the drunkards walk of stock prices. His pals followed suit.

In a moment, the air was white with curling streamers, a reporter for the New York Times observed. Hundreds caught in the meshes of electric wires and made a snowy canopy, and others floated downward and were caught by the crowd.

The fun was contagious. Serious men of finance became boys again, pressing against office windows to unspool paper onto the crowd. There was seemingly no end to it, the Times reporter wrote. Every window appeared to be a paper mill spouting out squirming lines of tape. Such was Wall Streets novel celebration.

With that, the ticker-tape parade was born.

During the next one hundred fifteen years, countless tons of celebratory confetti sailed from high-rise windows onto a stretch of Lower Broadway that became known as the Canyon of Heroes. Paper blizzards honored more than two hundred explorers and presidents, war heroes and athletes, astronauts and religious figures, luminaries from Einstein to Earhart, Churchill to Kennedy, Mandela to the Mets.

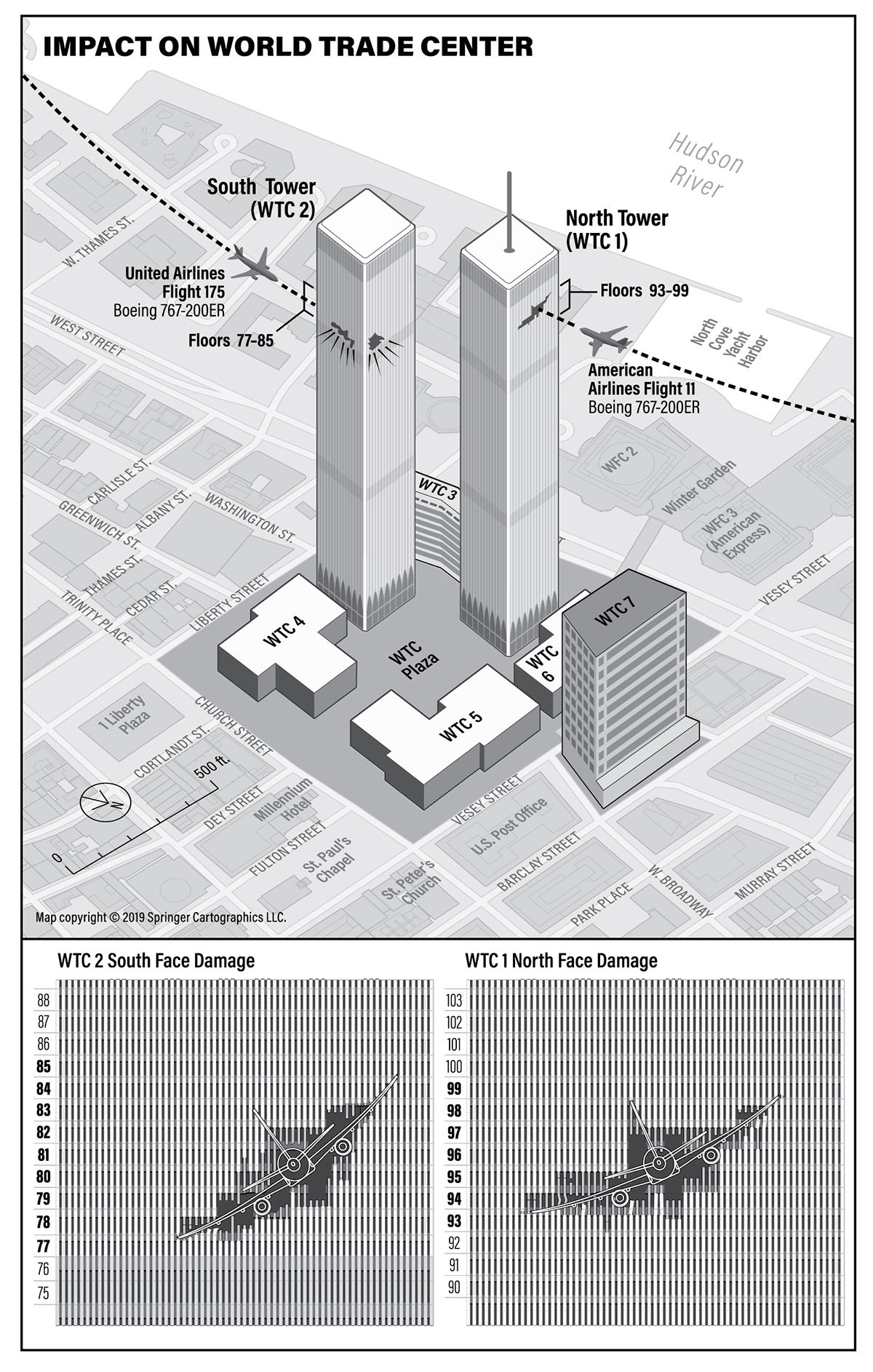

Then came September 11, 2001.

Torn open, aflame, weakening from within, the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center spewed paper like blood from an arterial wound. Legal documents and employee reviews. Pay stubs, birthday cards, takeout menus. Timesheets and blueprints, photographs and calendars, crayon drawings and love notes. Some in full, some in tatters, some in flames. A single scrap from the South Tower, tossed like a bottled message from a sinking ship, captured the days horror. In a scrawled hand, next to a bloody fingerprint, the note read:

84th floor

west office

12 People trapped

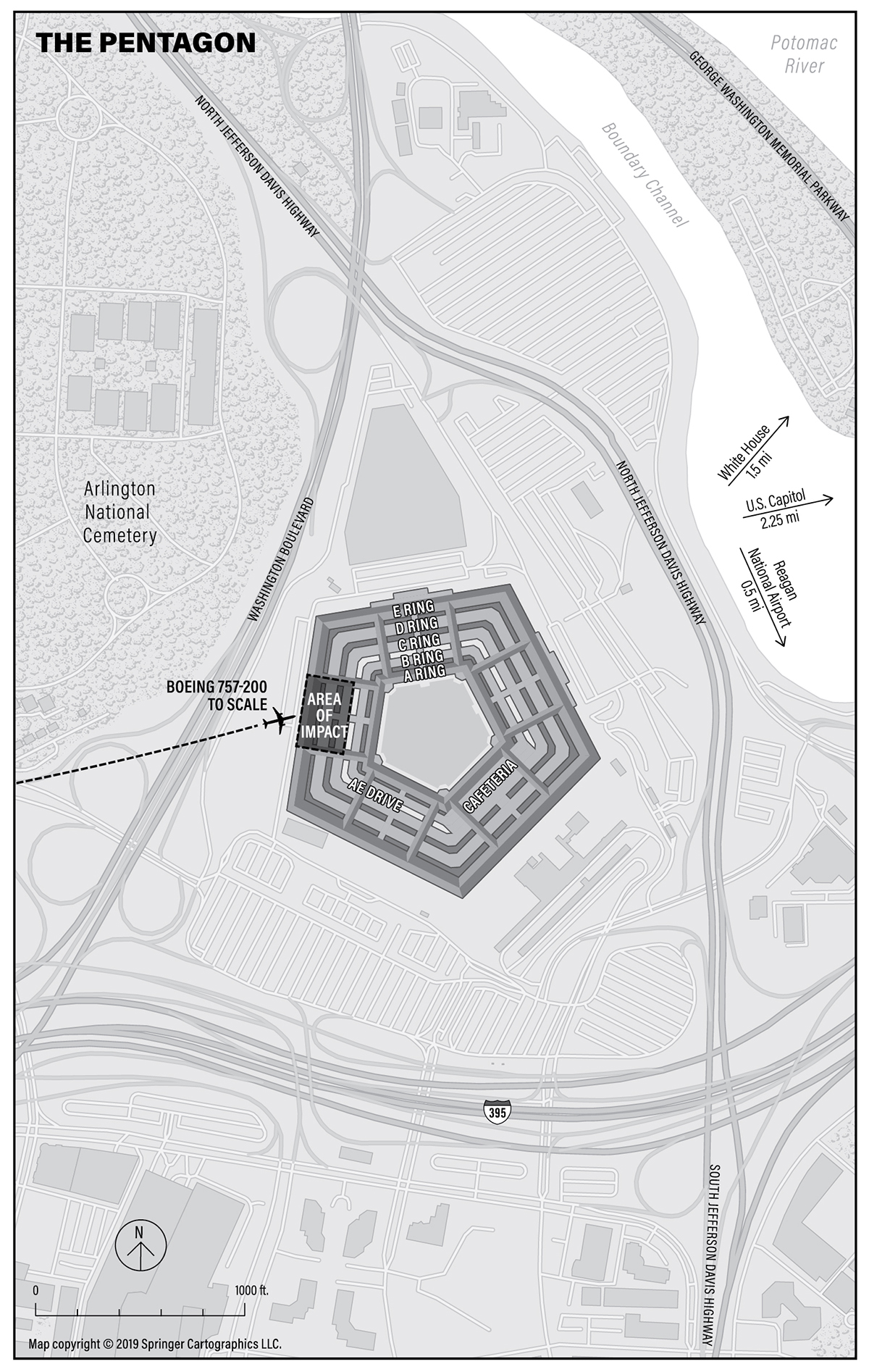

After the paper came the people. After the people came the buildings. After the buildings came the wars. The ashes cooled, but not the anguish. For years, New Yorkers couldnt stomach a ticker-tape parade, especially so near the hallowed hole renamed Ground Zero. Yet with time, the unthinkable often becomes acceptable.

In February 2008, the underdog New York Giants won the Super Bowl. Tens of thousands of football fans gathered to celebrate, just blocks from where steel beams rose for a dazzling Freedom Tower at One World Trade Center, an audacious middle finger to Americas enemies, taller and bolder than the boxy twins whose sanctified footprints the new building overlooked. As the victorious Giants rolled past, their joyful supporters danced in the streets as thirty-six tons of shredded paper fluttered down upon them.

Measured in ticker tape, the return to normal took less than seven years.

With time, news becomes history. And history, its been said, is what happened to other people. a word seldom used in the United States prior to the events now known as 9/11. (The month-and-day abbreviation became the universal shorthand for the attacks largely because the digits corresponded to the nations 9-1-1 emergency call system; theres no evidence the terrorists chose the date for that reason.)

Already an entire generation has no direct memory of 9/11, despite its daily effects on their lives. The historian Ian W. Toll described this progression in relation to another shocking enemy assault that also led to war: the raid on Pearl Harbor, sixty years earlier. The passage of time strips away the searing immediacy of the surprise attack and envelops it in layers of exposition and retrospective judgment, Toll wrote. Hindsight furnishes us with perspective on the crisis, but it also undercuts our ability to empathize with the immediate concerns of those who suffered through it. He quoted John H. McGoran, a sailor on the doomed battleship USS California: If you didnt go through it, there are no words that can adequately describe it; if you were there, then no words are necessary.

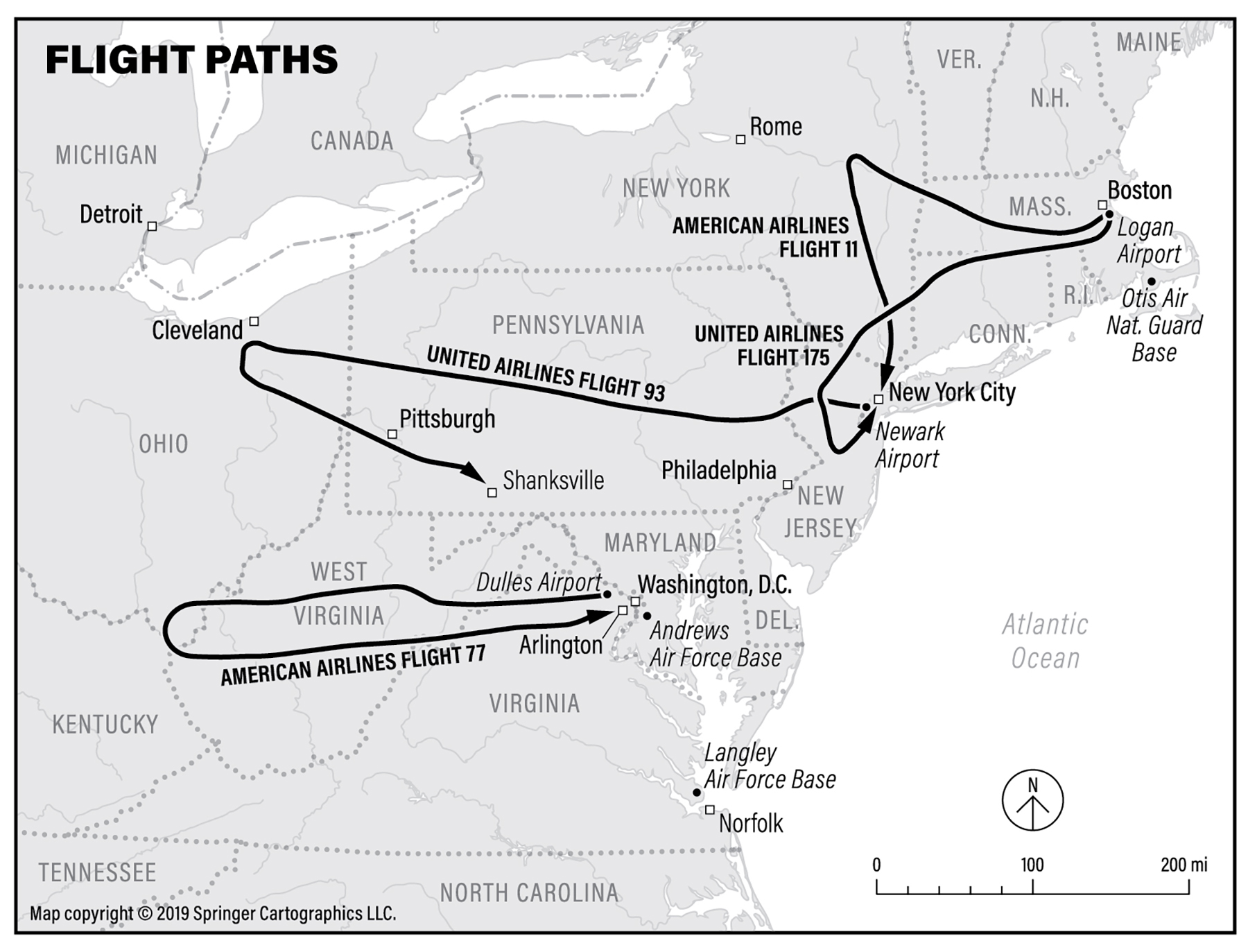

Even if words might fail, theyre the best hope to delay the descent of 9/11 into the well of history. That is the purpose of this book. The approach is to recount the chaotic day as a narrative in three parts: events in the air, on the ground, and in the aftermath, focusing on individuals whose actions and experiences range from heroic to heartbreaking to homicidal. For every account included here, a thousand others are equally important. Ive tried to choose stories that reveal the depth and breadth of the day without turning this into an encyclopedia. The goal is to provide a fresh perspective among readers for whom the attacks remain news, and to create something like memories for everyone else.

Another hope is more intimate: to attach names to some of the people directly affected by these events. Of the nearly three thousand men, women, and children killed on 9/11, arguably none can be considered a household name. The best known victim might be the so-called Falling Man, photographed plummeting from the North Tower of the World Trade Center. Yet even he remains nameless to most people, an anonymous icon.

This book has its roots in the day itself. On September 11, 2001, as a reporter for the Boston Globe, I wrote the lead news story about the attacks, with contributions from several dozen colleagues. The work was at once historic and local: both hijacked planes that struck the Twin Towers took flight from Bostons Logan International Airport. Five days later, with help from four reporters, I published a narrative called Six Lives that became the scale model for this book. It wove the stories of six people affected by, responsible for, or otherwise connected to the hijacking of American Airlines Flight 11 and the North Tower calamity. As we explained at the time, the story was designed to reveal a nations shared experience, as told through their memories and the memories of their loved ones. It also creates a memorial to all those who were killed, and provides a record for all who lived.