32.

INTRODUCTION

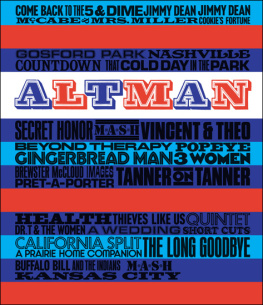

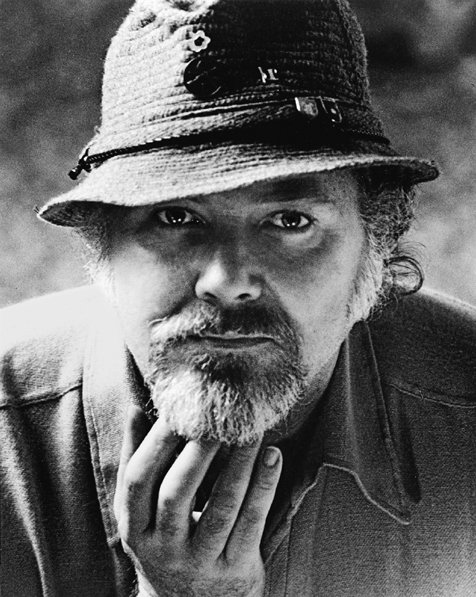

R OBERT A LTMAN drew you in, enlisted you in his schemes, took what he needed and gave what you asked. He trusted that youd be good, right for the part hed cast you in, and unless you screwed up hed give you free rein. He pulled you onto his pedestal, passed you a joint, then rocked so hard youd fall off together in a happy heap.

Bob did all that with me, a writer he met near the end of his life, someone with whom he could talk movies, baseball, the glory of a well-turned female leg, movies, politics, family, friendship, and movies. At first, Bob was cool to the idea of a book. His medium was film, and he considered it dangerous and distracting to publicly analyze himself. He relented under the condition that Id help him write a memoir of the art and craft of filmmaking, a book that would focus on his work and pay little attention to his personal life. He said his motive was a healthy paycheck from the publisher, and he meant itBob was far better at spending than saving. But he also knew hed have a chance to talk about his movies, something he loved almost as much as making them.

The deal was that when we were working, wed talk film, not life. He didnt want stories of his past deeds or misdeeds to fog the lens, and he didnt want anything to hurt his family, especially his wife, Kathryn Reed Altman. His one concession was a chapter that would sketch the broad contours of his past.

We began talking in long sessions at his homes in Malibu and Manhattan and at the New York office of his last company, Sandcastle 5 Productions. It soon became clear that the lines between his life and his work werent just blurry, they were almost nonexistent. After he returned from flying bombers in World War II, planning and making movies defined nearly everything he did. The films he eventually made werent overtly autobiographicalnot even Kansas City, which is a sepia-toned memory of a world he glimpsed as a boy. Not The Player, either; theres no evidence that he ever killed a writer, though he might have fantasized about it. He didnt need to make movies about himself because the entire process of filmmaking was his adult life, a stage for his passions, his rages, his triumphs, his humor, his visions, his failures, his gifts.

We talked more, and I secretly fretted that the limits hed set would make our book a clinical rendering of the outsized, extraordinary, flesh-and-blood man Id come to know. Me: Whyd you film the gun-fight in McCabe in a snowstorm? Bob: Because it snowed that day.

My concerns got worse one night when we attended the Malibu Celebration of Film for a showing of his last movie, A Prairie Home Companion. The film had been out for months, and I can only guess how many times hed seen it. But when we returned to his home, Bob was fuming. Wed sat in the second row, behind a couple and their antsy twelve-year-old son. If that fucking kid got up one more time, Bob growled, Id have strangled him and his father. Separating the man from his film, physically or otherwise, wasnt a good idea.

A month later, Bob died. My concerns were trivial in context and swallowed by sadness. Academic, as well: Our work was unfinished. But a new idea emerged. Our talks, Robert Altmans final sustained interviews, would form the backbone of a book about his work and his life, rough edges and all. Kathryn agreed, recognizing that to understand the films Bob made and the man he was, the man she loved, meant examining the whole remarkable, complicated, combustible package.

What followed for me was an Altmanesque tour from birth to death. Scenes took place in Kansas City, California, and New York, with side trips to such places as Burlington, Vermont, and Plum Island, in Massachusetts, and phone calls throughout the United States, Canada, Europe, South America, and even to a movie set in Morocco. The cast was huge and varied, from A-list stars to complete unknowns, many from the world of film but some purely from the world of Altman.

Bob told me that he and his cowriters created forty-eight characters in A Wedding only because that was double the number in Nashville. It was a conceit, a caprice; he wanted to see how many individual voices he could establish in a celluloid choir without drowning the audience in cacophony. It took nearly four times as many characters to survey his life. Their thoughts, reminiscences, opinions, regrets, praise, criticism, and in a few cases their dreams, are presented here in something approaching chronological order.

Thats not to say the result is a neat, complete tale, with a moral and a point and a bow on top. That isnt Bob. He didnt think much of linear storytelling, and he wouldnt have wanted his life rendered that way. In fact, he disliked the word story, believing that a plot should be secondary to an exploration of pure (or, even better, impure) human behavior. He also hated the ventriloquism of a single writers voice emanating from many diverse characters, as if a baker and a surgeon, or a phone-sex worker and a grieving jazz singer, would use the same syntax. See Short Cuts again if you doubt that. He loved the chaotic nature of real life, with conflicting perspectives, surprising twists, unexplained actions, and ambiguous endings. He especially loved many voices, sometimes arguing, sometimes agreeing, ideally overlapping, a cocktail party or a street scene captured as he experienced it.

Bob was no more conventional when he wasnt behind a camera, and I tried to reflect that, too. As James Caan says, in Hollywood Trust me is code for Fuck you. Bob didnt speak in code. In a world of air kisses and backstabbing embraces, he spoke his mind. No, he roared his mind. He believed that every capitulation large and small was tallied somewhere, each one a new link in a chain that choked off creativity. His refusal to play along cost him, personally and professionally, but he wouldnt complain and he wouldnt change. He lived the way he made movies. At times it was messy, but it was completely of his own design.

Theres no way to replicate in print what Bob accomplished on film and in life, but an oral biography seemed the next best thing. I hope hed agree.

In the transcripts of our talks, theres a passage that Ive reread more times than I care to admit. Its an interruption, really, the sort of thing a transcriptionist usually omits. But for some reason its there, embedded in a discussion about viewing an artists work through the prism of his life.

Excuse me, Bob says, reaching for a ringing phone. Its his producer, Wren Arthur. Lemme call you back, he tells her. Mitch is here on the floor next to me. Im lying on the couch and hes sitting on the floor, and our heads are next to each other.

Ive held on to that moment, trying to keep my head next to Bobs, to fairly yet fully explore his work