CONTENTS

Martin Scorsese

Giulia DAgnolo Vallan

Frank Barhydt

Michael Murphy

Giulia DAgnolo Vallan

Roger Ebert

Pauline Kael

Giulia DAgnolo Vallan

A Shadow Play of What We Have Become and Where We Might Look for WisdomKurt Vonnegut Jr.

Pauline Kael

Giulia DAgnolo Vallan

Giulia DAgnolo Vallan.

E. L. Doctorow

Alan Rudolph

Giulia DAgnolo Vallan

Giulia DAgnolo Vallan

Michael Murphy

Giulia DAgnolo Vallan

Michael Tolkin

Tess Gallagher

Giulia DAgnolo Vallan

Giulia DAgnolo Vallan

James Franco

Garrison Keillor

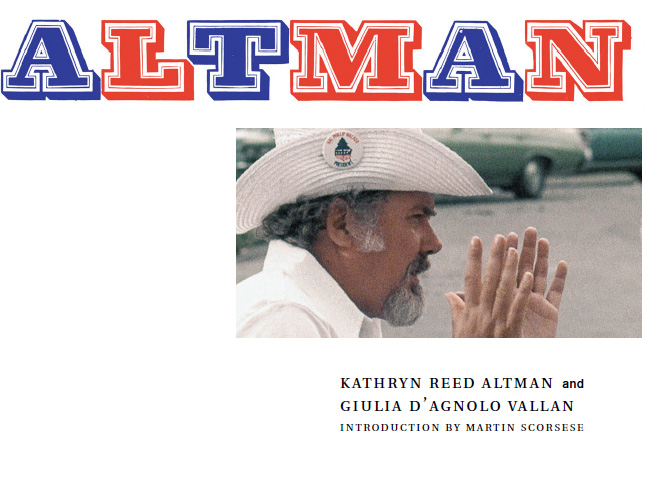

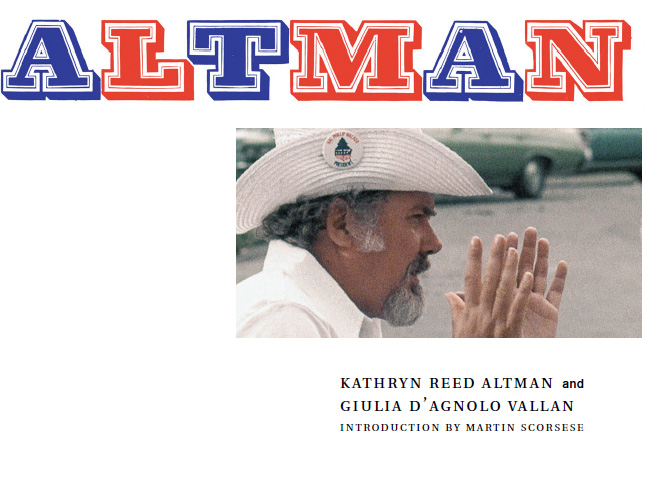

INTRODUCTION

BY MARTIN SCORSESE

Robert Altman and I crossed paths fairly often over the years, but I felt like I got to know him intimately through his films. His signature. His human imprint as an artist, as recognizable and familiar as Renoirs brushstrokes and Debussys orchestrations. It seems increasingly precious as the years go by, particularly now, when individual expression in movie-making is so precarious.

I suppose that my first Altman film was M*A*S*Hit was for many people. It took us all by surprise. The irreverence, the freedom, the mixture of comedy and carnage, the Korean renditions of American hits and the voice over the loudspeaker as running commentary or counterpoint, the creative use of the zoom lens and the long lens, the multiple voices on the soundtrackhe was like a great jazz musician, taking us all along on a grand artistic journey.

He changed the way we looked at people and places and listened to voices, and he really changed our understanding of exactly what a scene was. Bob made so many wonderful pictures, but finally its all the work taken together that is such a source of wonder.

Bob and I would cross paths from time to time every few years or so, and it was always memorable. He was there at the New York Film Festival in 1973 when Mean Streets was shown, which was a big event for me in so many ways. We met, and I remember that he was so gracious, so reassuring, and entirely complimentary. He really went out of his way for me. It was inspiring, and it meant the world to me.

Ten years later, we ran into each other at an official function on a yacht. We struck up a conversation, and we discovered that we both had pictures, made at the same studio, that had been pulledThe King of Comedy for me, HealtH for him. There we were, both at a crossroads. Given the way things were going in the industry, neither of us could get a picture funded. We were marked men. For a while, at least.

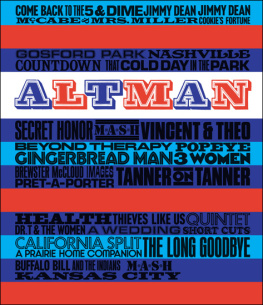

Bobs solution to the problem was very simple: He just kept working. He persevered. Mind you, this is when he was almost sixty, a time of life when many other people would have given up. He was just getting his second windor was it his third? Or maybe his fourth? Bob started in the world of industrial filmmaking, then moved into television with episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents, Whirlybirds, Peter Gunn, Bonanza, and Combat!, among others. He was able to shift to features in the late sixties, which led to M*A*S*H and that amazing period in the seventies when he made one remarkable picture after another. Then he went into the period I was discussing before, what I guess he might have called his journeyman years in the eighties.

This was inspiring to me, and it should be a model to all young film-makers. He probably figured, Look: This is the business were in, this is the way it isyou gamble, and sometimes you win, and sometimes you losebut you keep playing with whatever you have. He just plowed ahead, working under all kinds of conditions. He shot adaptations of plays by David Rabe and Sam Shepard and Christopher Durangsome on Super 16, like the beautiful Come Back to the 5 & Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean by Ed Graczyk. He did televisionsome one-act plays by Pinter, a tremendous adaptation of The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial. He did some wonderful work in Europe, including Vincent & Theo. And it seemed that his years in the wilderness only increased his motivation to steal his way back into the system. Which he did in the nineties, with The Player. Imagine breaking back into Hollywood, like a guerrilla fighter, with a picture that cast as tough and sharp and cynical an eye on the movie business as Sunset Boulevard had forty years earlierand perhaps even less forgivingly than Billy Wilders classic. The Player was made with the energy of a young man and the wisdom of an older one.

No matter what the circumstances, Bobs films remained his and his alone. I never cease to be amazed by the sheer range of his work, and the apparent ease of it. It seemed like he could take on absolutely any kind of material, from The Long Goodbye to The Gingerbread Man, from Thieves Like Us to Gosford Park, from Kansas City to Vincent & Theo, and pull off two things at once: do justice to the material and incorporate the film into his own universe. He did it with apparent ease, and with such evident grace. I was astonished by Gosford Park, the way that he simply went off to England and confidently made this movie, with all these characters coming alive, the movement so fluid, the drama among the people so exact, the sense of place and weather so sharp. (Bob made extraordinary use of weather in picture after picturethe snow in McCabe & Mrs. Miller, the desert heat in 3 Women, the falling rain in The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial, to name just a few examples.) And there are all those little moments, grace notes that finally arent so little, and that are the heart of Bobs picturesfor instance, Alan Bates as the butler, standing around a corner, listening secretly to Ivor Novello (Jeremy Northam) playing the piano and tapping his foot to the rhythm.

There are so many of Bobs pictures that I cherish: Nashville, of coursetheres no other picture like it, a true American epic; Thieves Like Us and California Split, two remarkable pictures that must have been made almost back-to-back; Cookies Fortune, of his wonderful group movies, and The Gingerbread Man, an unusual thriller in which the atmosphere is the star; Kansas City, a truly great musical film; and, of course, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, probably one of the most beautiful American films ever made. Its a favorite of mine, for many reasons. First of all, theres the sense of authenticitytheres such a powerfully evocative sense of life on the frontier, of the little town in the process of being built, and you feel like youre really living with the characters. And then theres Warren Beattys McCabe, like no other character I know of in movies: a dreamer whos talked himself into believing that hes some kind of tough guy but who isnt at all; and Julie Christies Mrs. Miller, who is much harder than McCabe but who softens herself for him, to protect his sense of masculinity. And its still remarkable to me that Bob was able to pull off that ending: the quiet, the falling snow, the fire and the people running to put it out, and, in the end, two souls fading into oblivion.

Next page